Eduardo Berliner’s works spring from the intercrossing of various sources, including daily graphic notations he makes in small notebooks, photographs taken during outings around the city, his study of 18th- and 19th-century European painters such as Goya, Courbet, and Manet, mnemonic images, scenes from films and from children’s stories, and other references. But in his case, the most striking effect about his works is that, although they evoke something already seen or known, they are not reducible to anything that could be priorly described or named. Berliner’s works rather seem to represent what is ineffable about them.

Eduardo Berliner belongs to a generation of Brazilian artists who revalorized painting as a contemporary artistic language. According to certain critics, these painters share in common the practice of appropriating preexisting images—photographs or images that refer to the history of painting and its genres—in order to conceive a third image, whose power is revealed when it is distanced from its image of origin.1 1 Cf. Mesquita, Tiago, “A pintura de imagem,” in: Isabel Diegues and Frederico Coelhes (eds.), Pintura brasileira séc. XXI. Rio de Janeiro, Cobogó, 2011, pp. 270–279. This process, which we can also characterize as a sort of estrangement, is what makes part of this production highly interesting. It is precisely in the space established between the referents and the final result that the pictorial practice takes on a new meaning.

This procedure has been explored by Berliner since the beginning of his production as an artist, in the mid-2000s. His paintings, watercolors, drawings, objects, and prints spring from the intercrossing of various sources, including daily graphic notations he makes in small notebooks, photographs taken during outings around the city, his study of 18th- and 19th-century European painters such as Goya, Courbet, and Manet, mnemonic images, scenes from films and from children’s stories, and other references. But in his case, the most striking effect about his works is that, although they evoke something already seen or known, they are not reducible to anything that could be priorly described or named. Berliner’s works rather seem to represent what is ineffable about them.

There is an ambiguity in his images that is manifested on various levels. First, the search for a quality pictorial practice and self-awareness are associated to the world of latent violence and perversion that uncannily seems both strange and familiar. I believe that the shock effect of his works stems precisely from this. On the one hand, Berliner reproduces scenes that we have already seen on various previous occasions and which, in and of themselves, contain nothing specifically frightening; but when, on the other hand, transposed to the surface of the canvas they provoke a sense of abhorrence or a feeling of horror. This is the case, for example, with his paintings Portão (2013, Gate) and Otite (2013, Otitis).

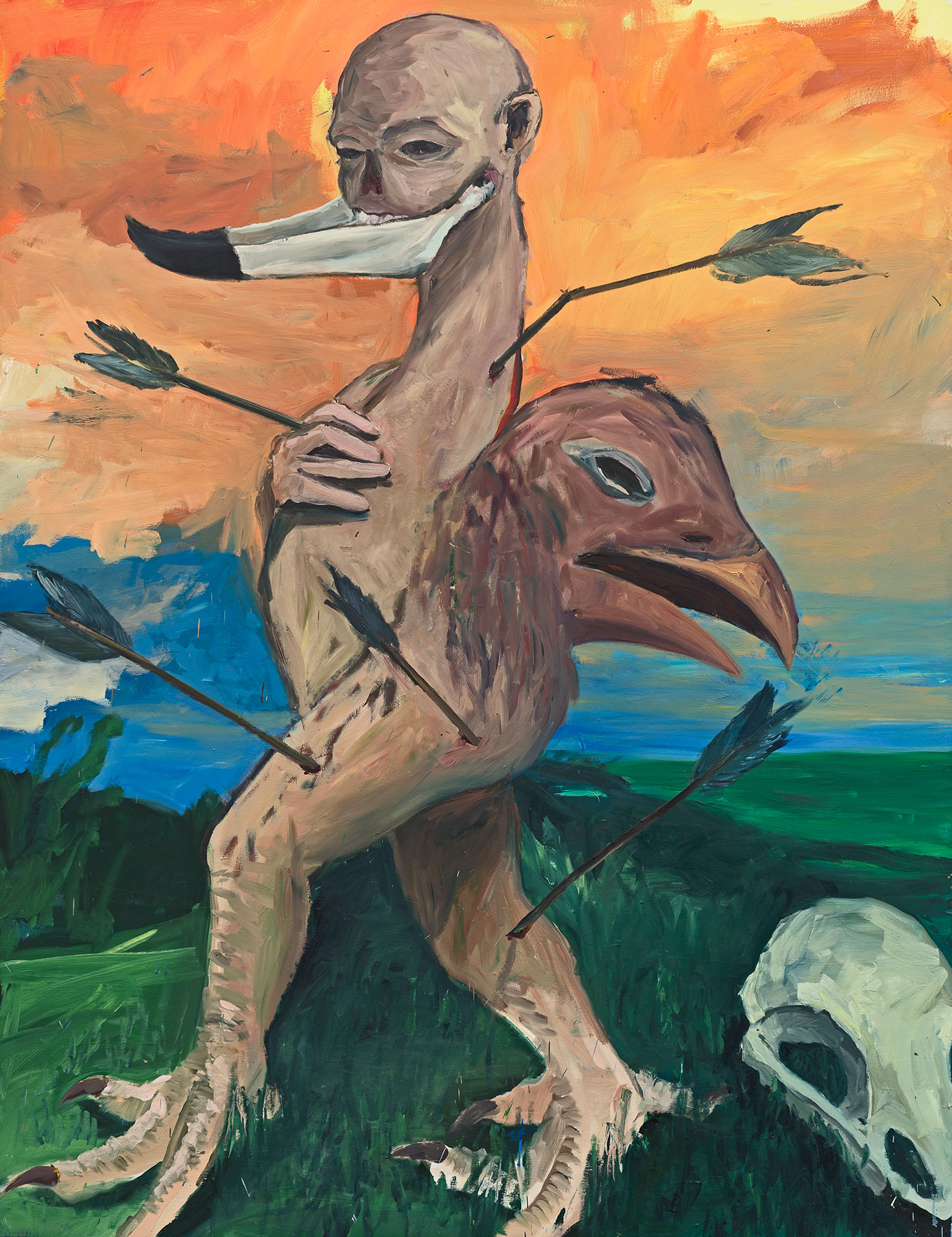

Apart from that, however, the summoning of this oneiric or imaginary world, through images in which the objects take on a life of their own, animals become equal to men, and hybrid beings gain existence, is not exactly disquieting in and of itself. In fact, these images are reminiscent of familiar things such as ancient legends, folk festivals, children’s dreams, war photos, comic strips, or scenes from horror movies. In a certain way, they pertain to the context of a mass culture that bombards the spectator with violent and perverse images, in light of which we unconsciously learn to become desensitized in order to protect ourselves. When presented in such glaring directness on the canvases, however, these figurations provoke pangs of uneasiness and estrangement, as though we suddenly became aware of the aggressiveness they symbolize, and of their inherent association with Western culture. This is the case in the painting Cabide (2013, Clothes Rack), in which a childhood memory gains a terrifying form, or A águia flechada (2013, Eagle Shot with Arrows), a painting that evokes an unknown but age-old story of sacrifice.

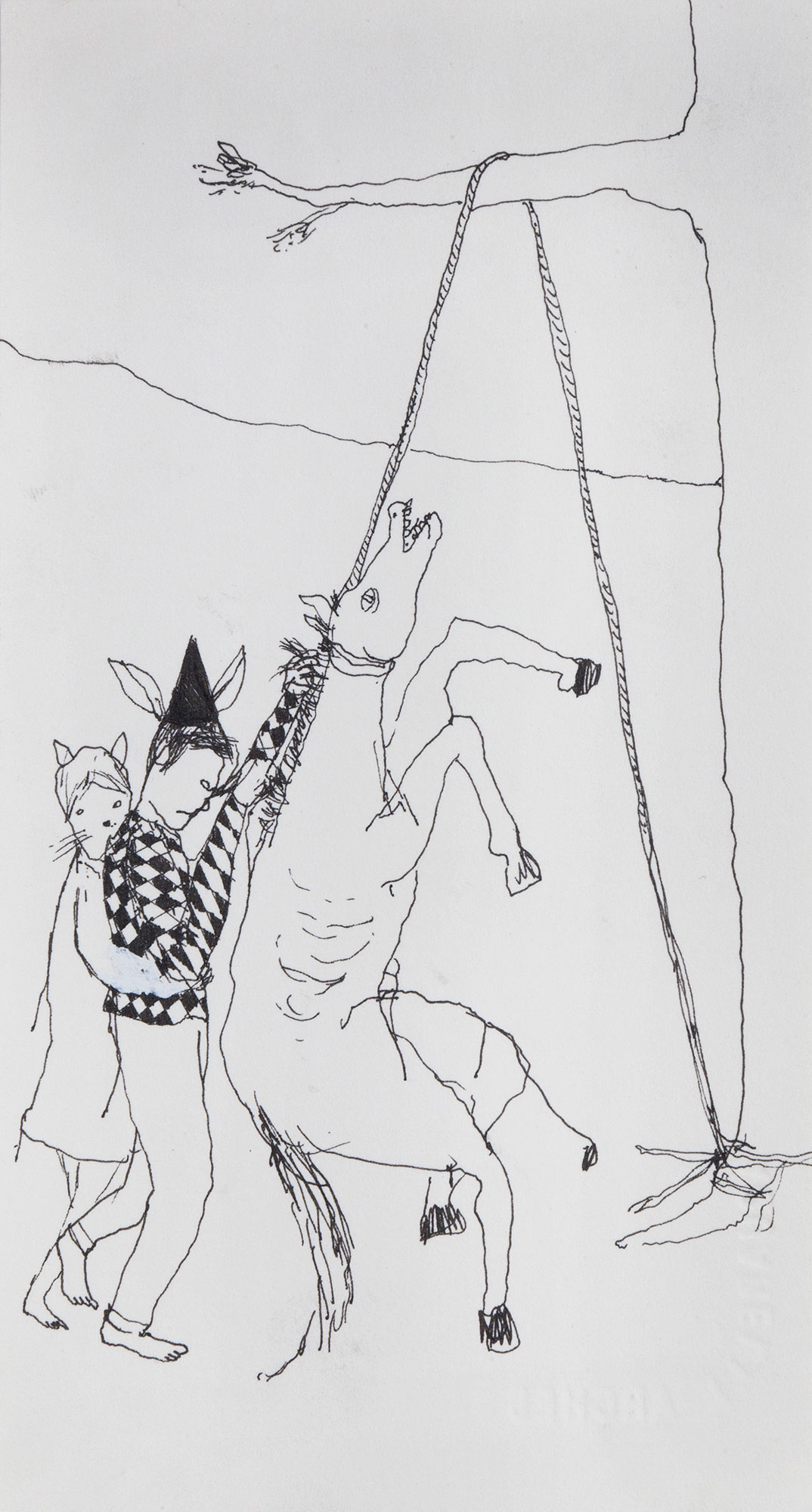

In the instance of his watercolors and drawings, such as Strange Fruit, Dança (Dance) or Enforcando um cavalo (Hanging a Horse), made between 2012 and 2013, the delicate lines and colors suggest the intimacy of a secret, which exists in the private realm or in the unconscious. When represented in images, however, these situations that involve the violation of the body and sacrificial violence undergo a process of naturalization, though still remaining brutal.

Note that the artist generally shows these works in groups and almost never on their own. The view of the group suggests a narrative element that to me is fundamental for an understanding of Berliner’s production. Each work seems to indicate an event taking place, a part of a story with an open-ended meaning.

These figurations moreover indicate that phantasmagorical fiction can become the inverse of a reality which, in the case of contemporary life, is nearer and more present than we would like. In Brazil, various artists have worked to show the somber side of tropical culture, emphasizing both the gratuitous nature of its bounty as well as the violent character of its tradition. In the sphere of visual arts, names like Oswaldo Goeldi, Iberê Camargo, Tunga, Nuno Ramos, among others, have expressed this formative contradiction of the Brazilian cultural existence. From time to time, and depending on historical events, this conflict emerges with renewed power. Eduardo Berliner’s works, though fictional, nevertheless allude to this real-world condition.

Taisa Palhares, 2017 Taisa Palhares is an Art Critic and Professor of Philosophy of Art at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, Brazil.

(Translated by John Norman)