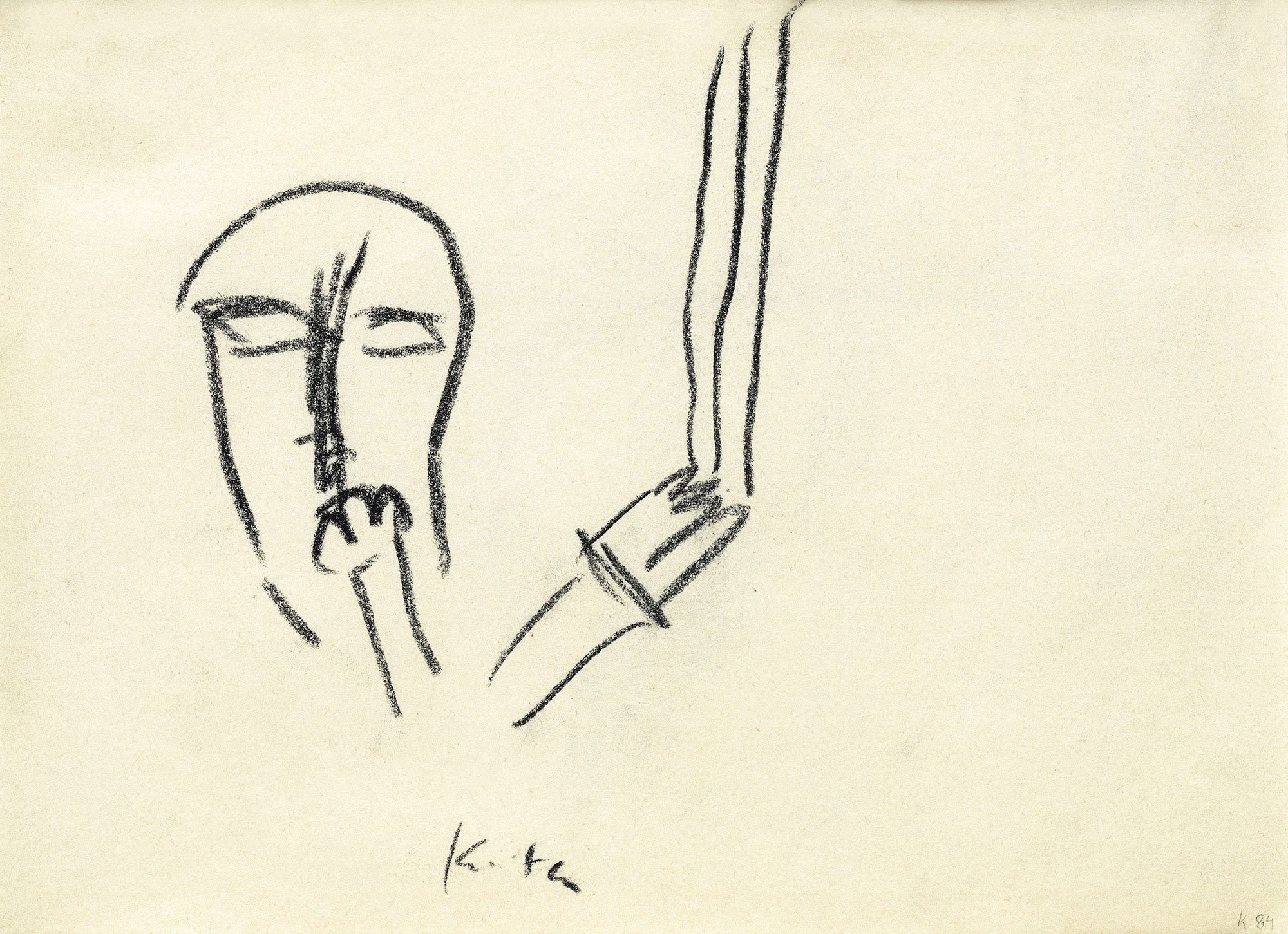

The 81 drawings in the Daros Latinamerica Collection are a perfect corpus for outlining drama as the constant and central theme of Guillermo Kuitca’s work, achieved through the persistent representation of confinement, instability and imbalance—without, however, abandoning humor. Created between 1981 and 1996, the drawings display the fundamental issues of those years and therefore constitute a revealing retrospective collection.

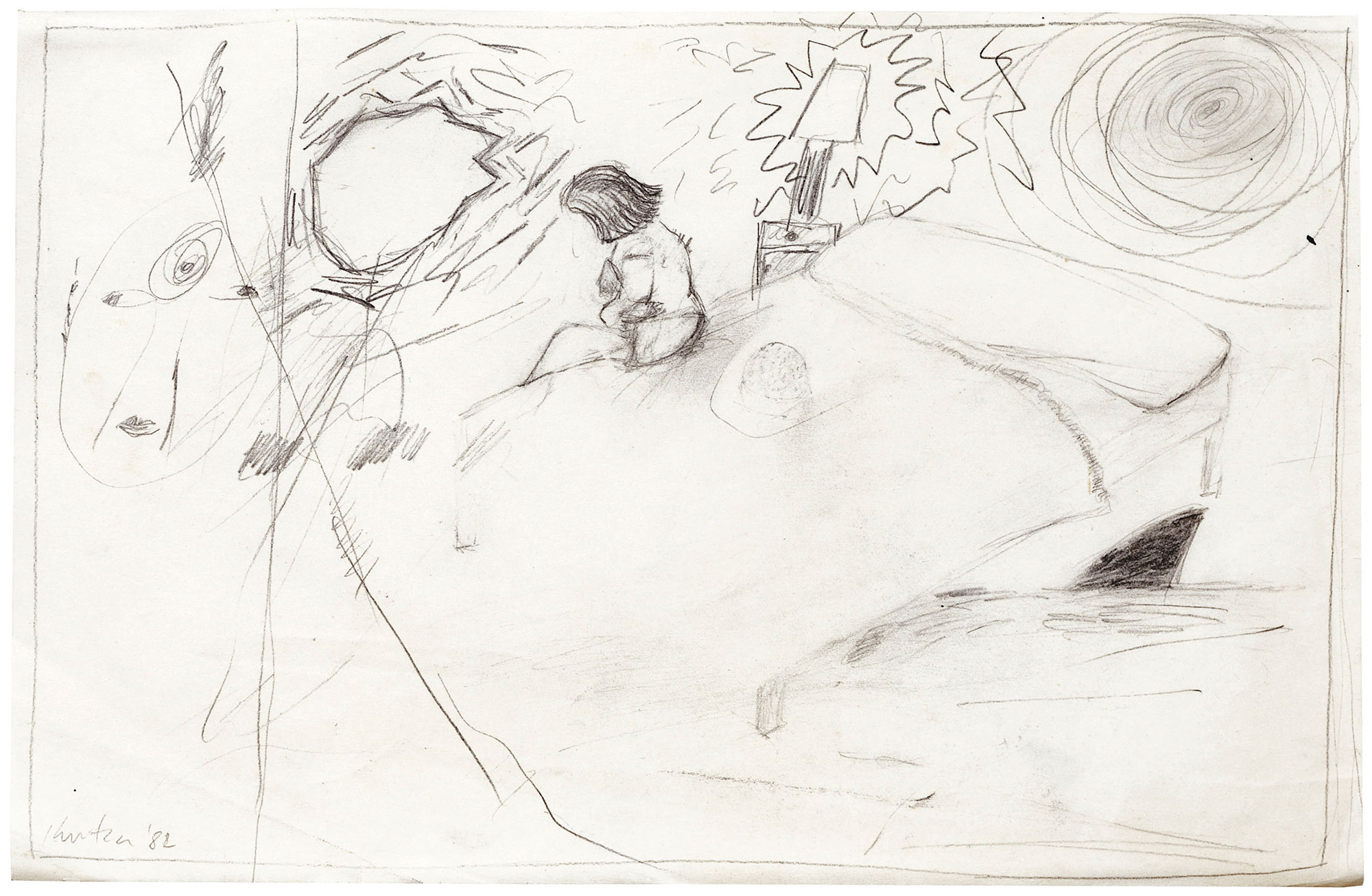

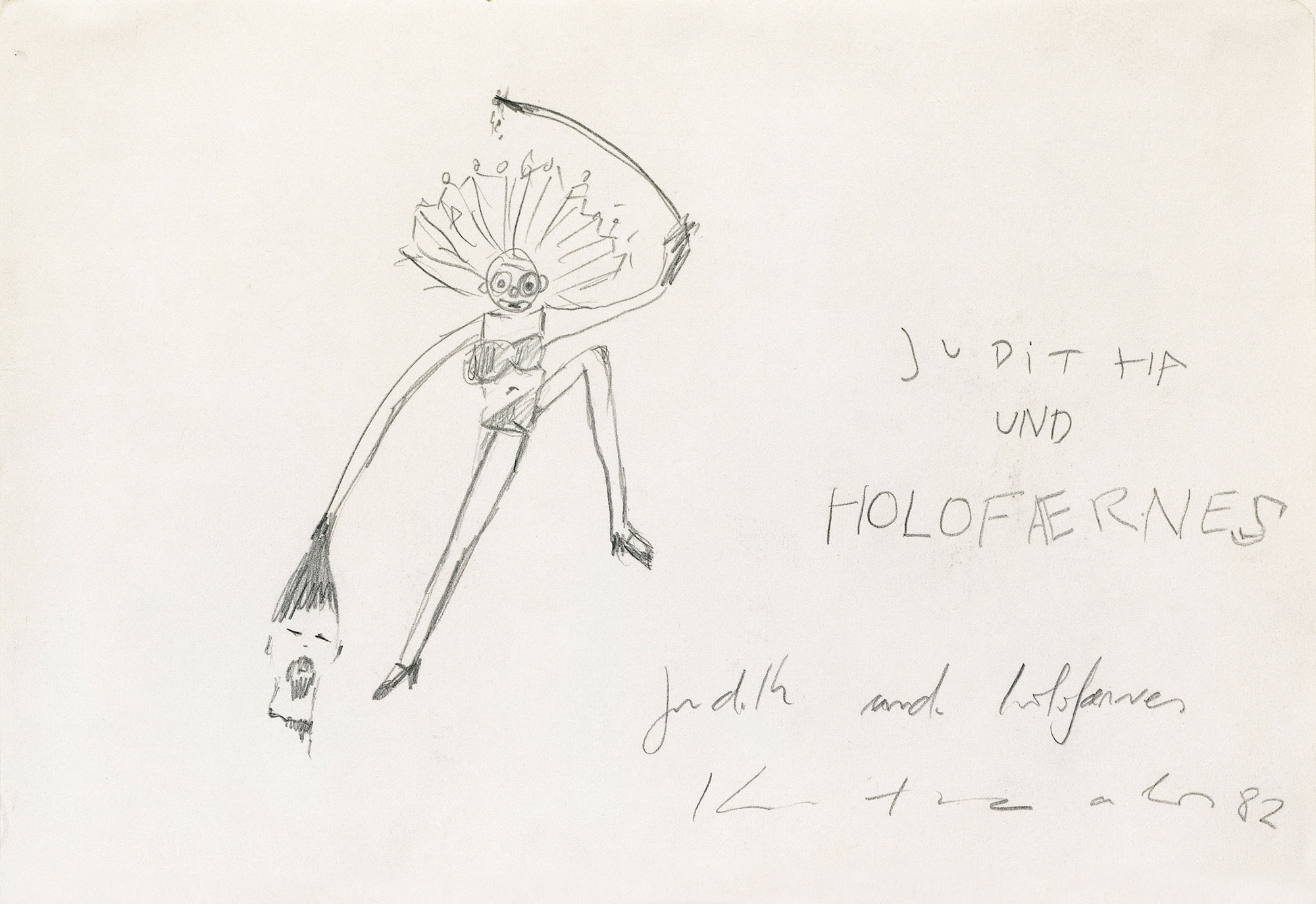

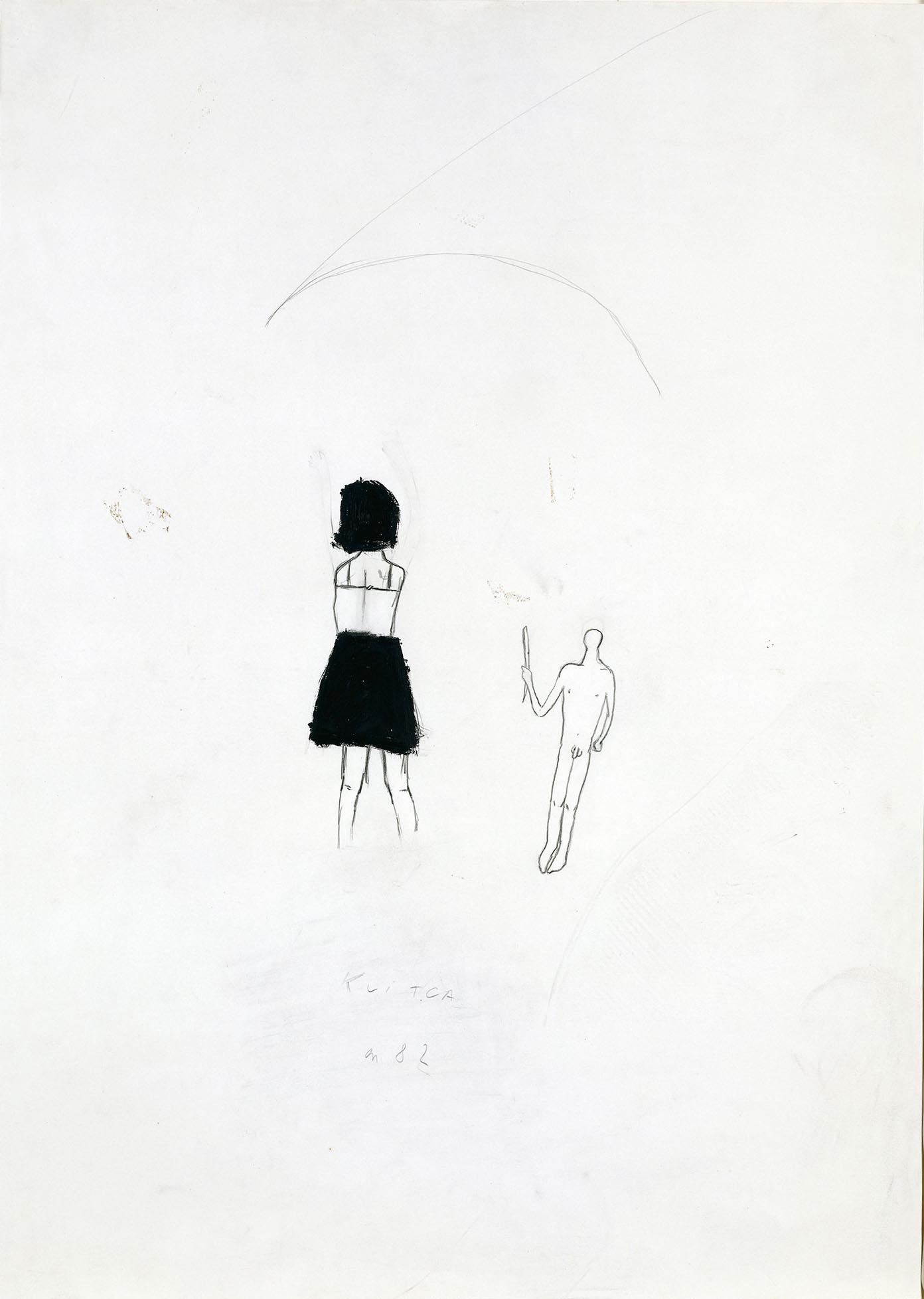

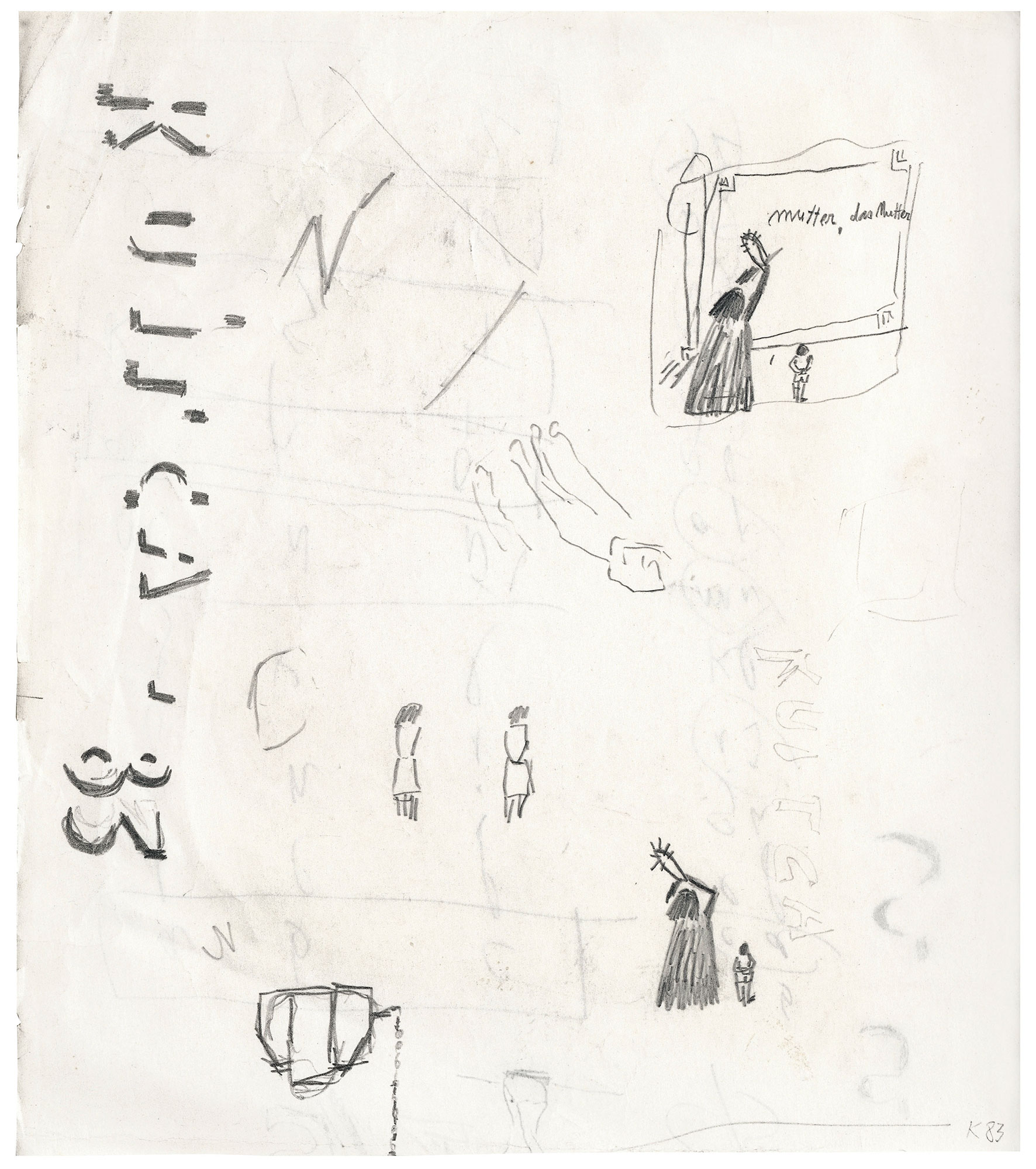

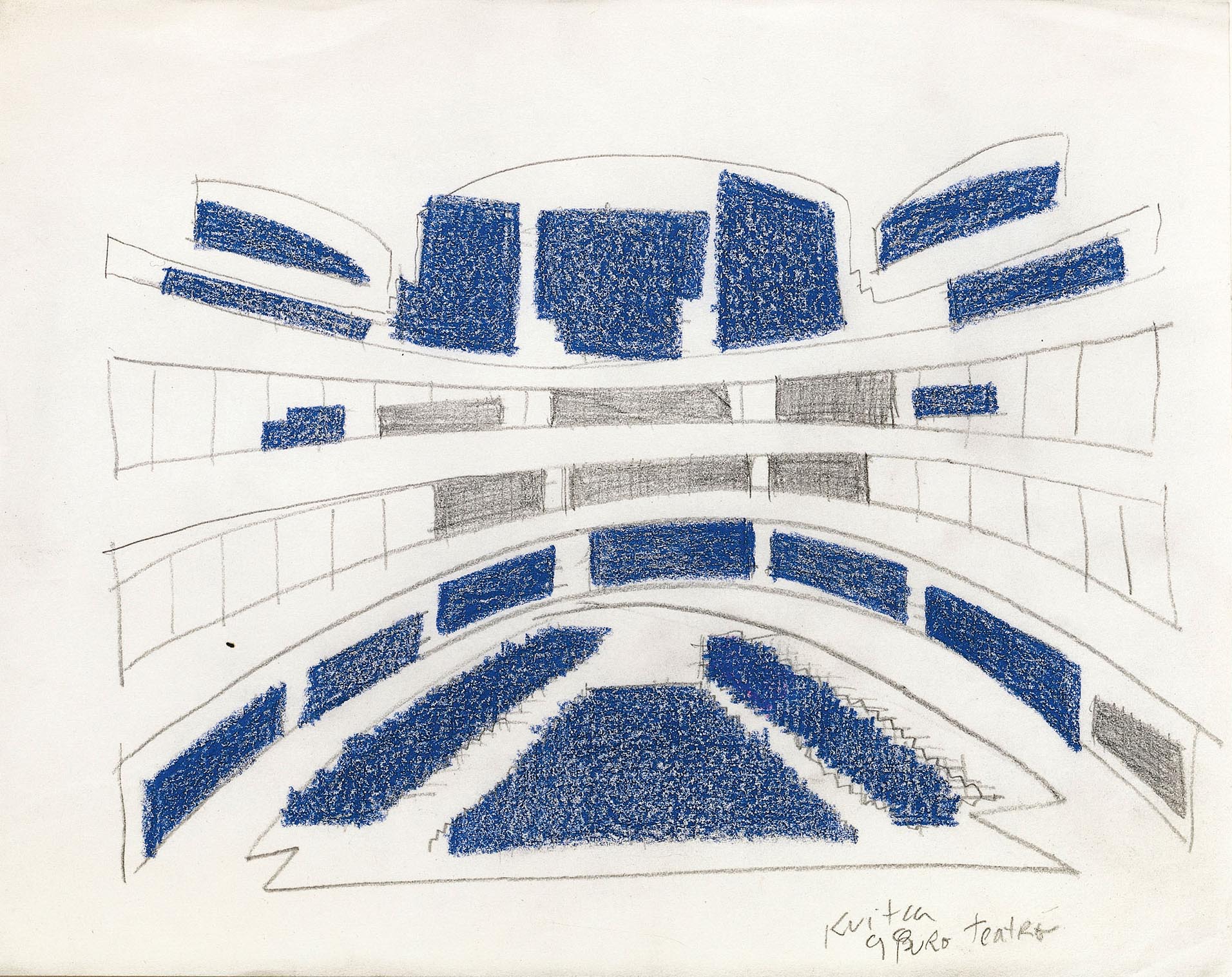

When Guillermo Kuitca began his career in Buenos Aires in the late 1970s as a very young man, he displayed his interest early on in the dramatic, as expressed in spatial and theatrical settings, whether classic or of his own creation. The motifs that nurtured his first paintings and theatrical works were sadism within the family, tragedy, insanity, and the traces of great wars and private battles.

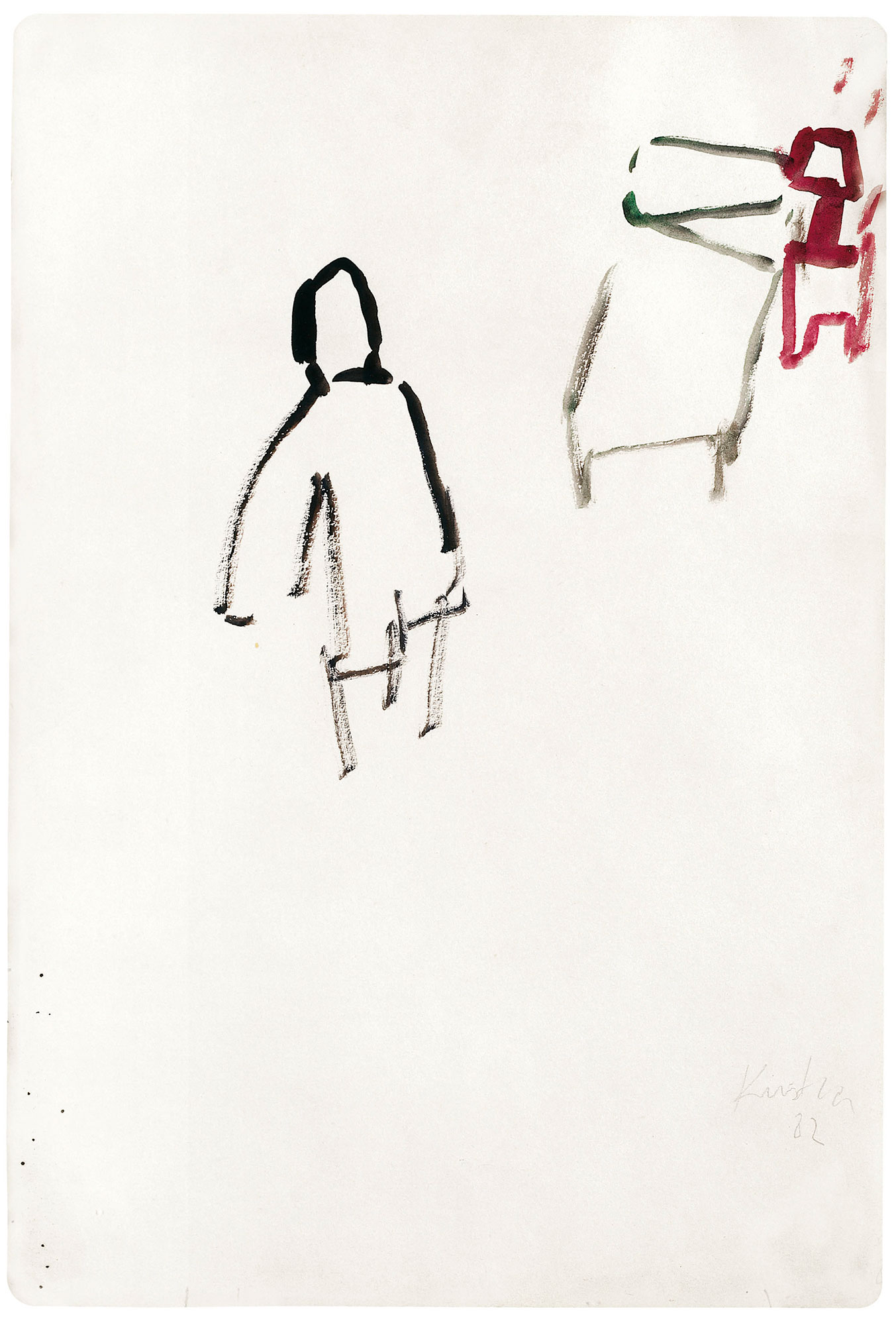

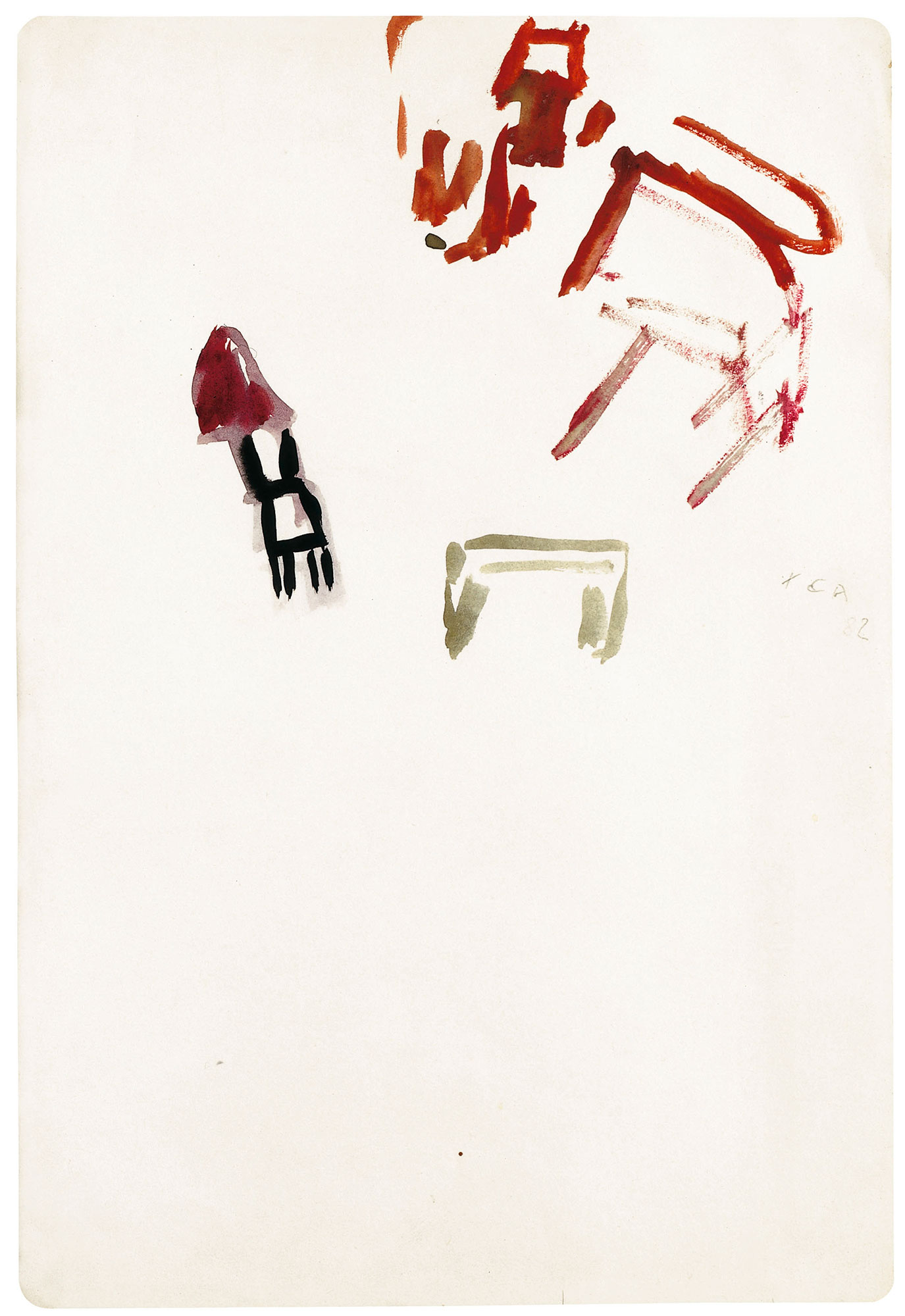

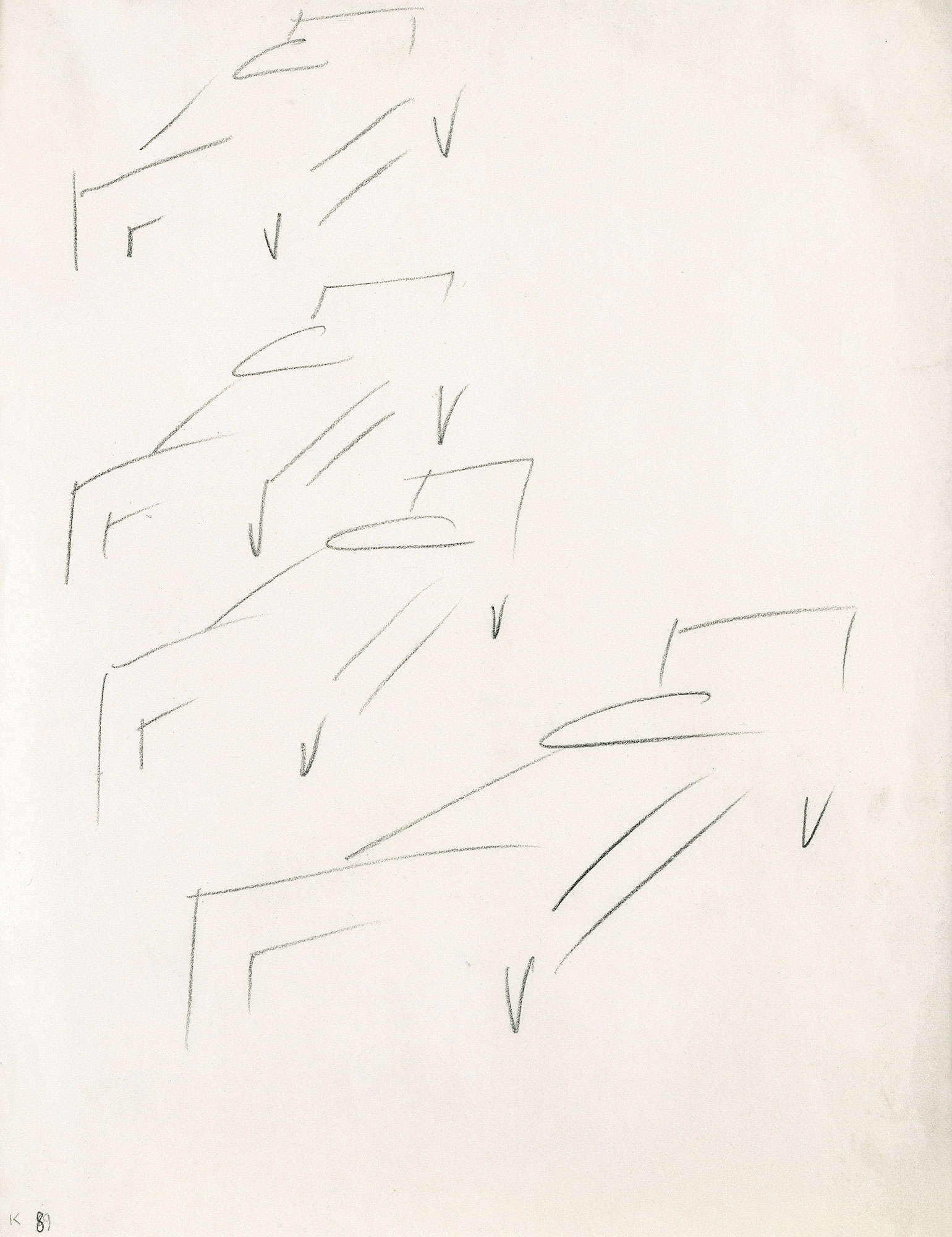

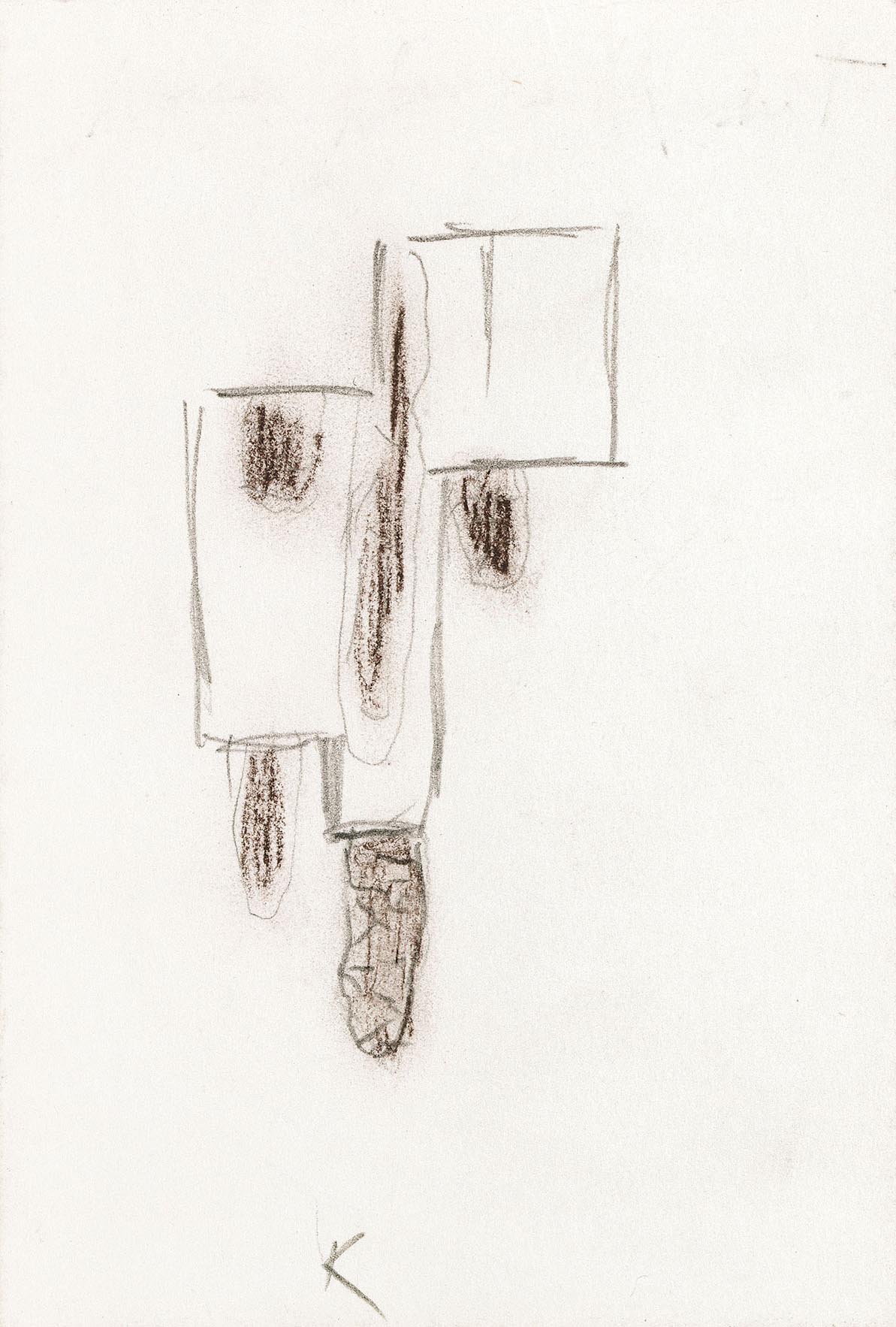

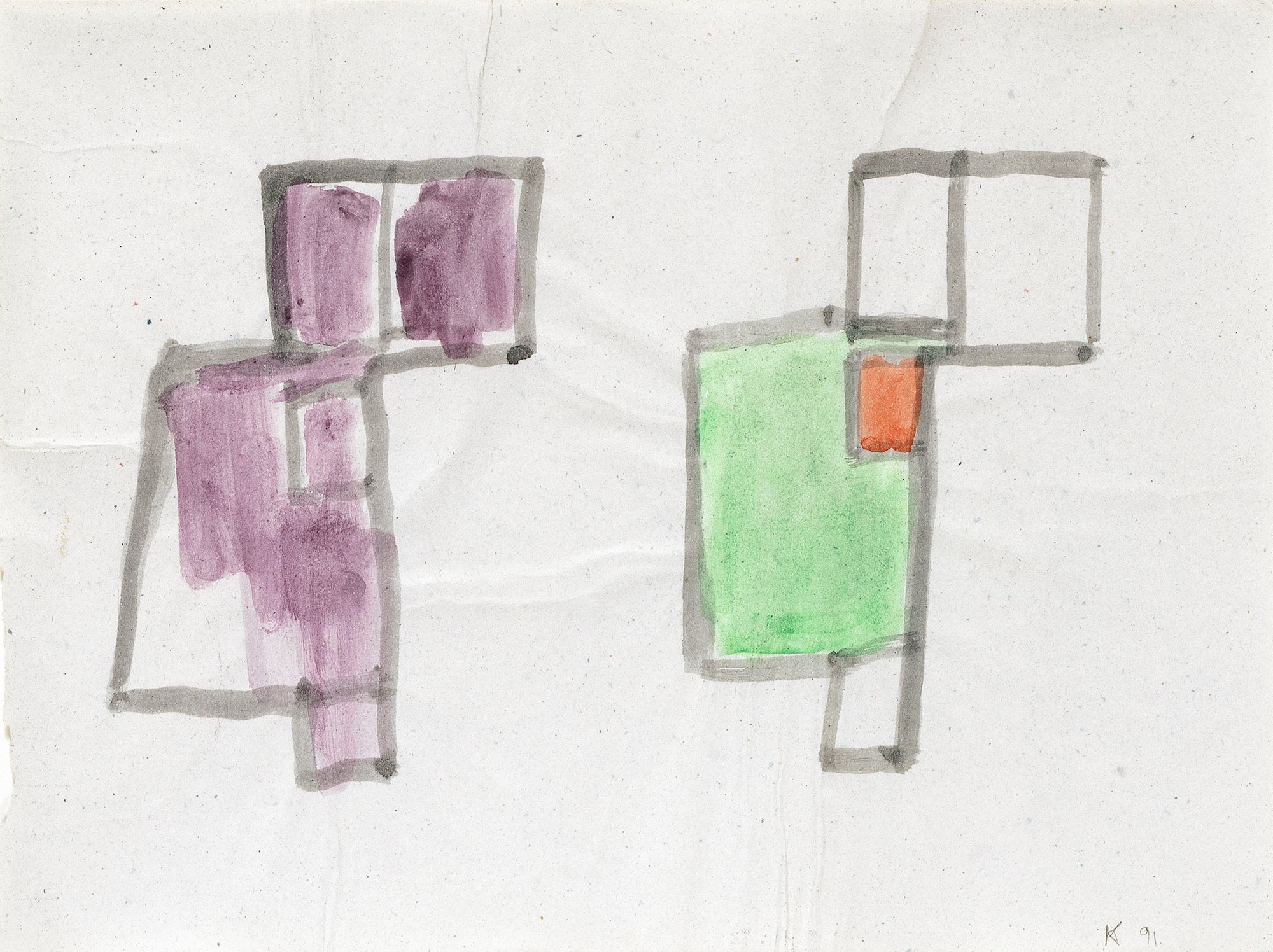

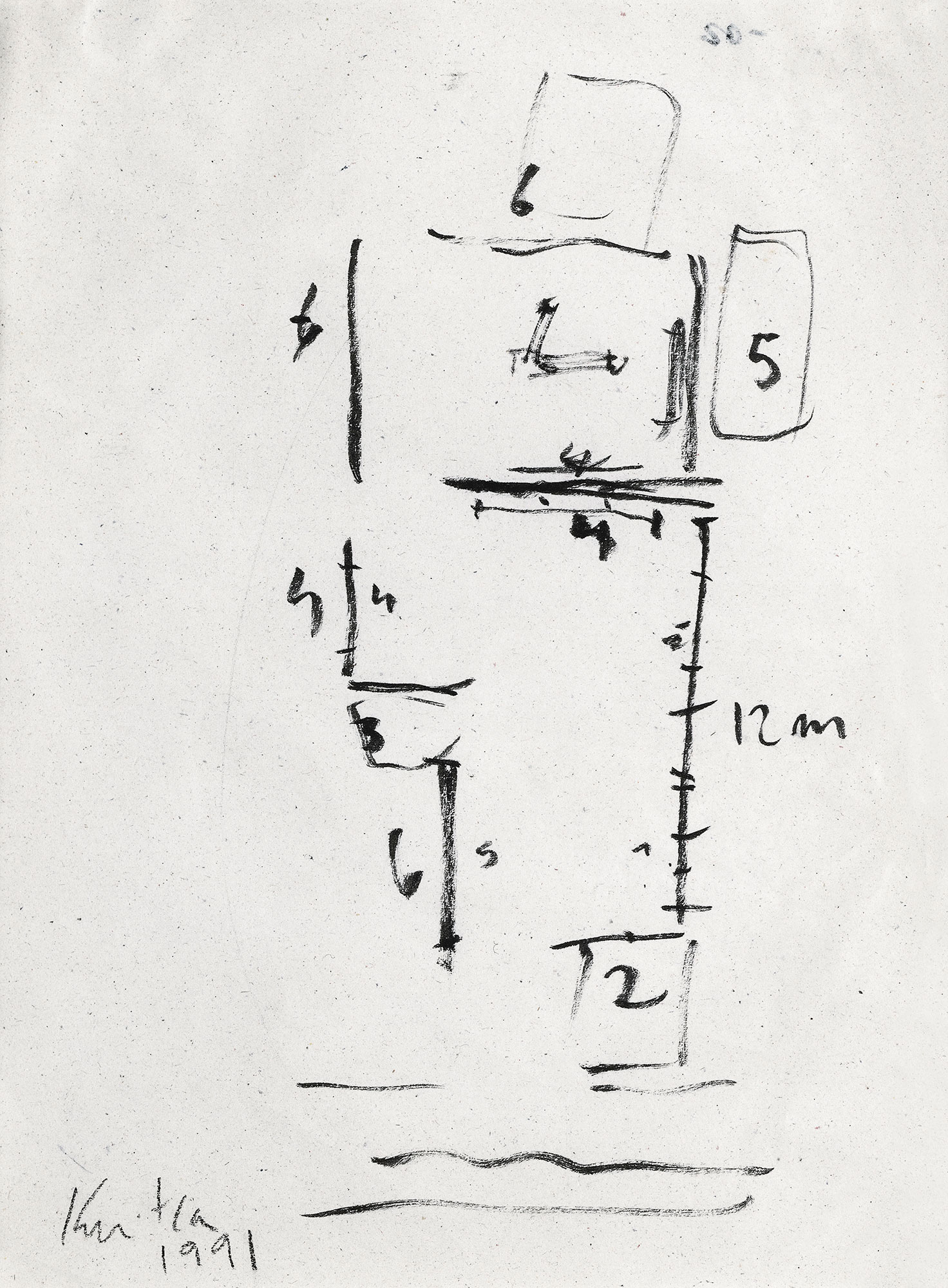

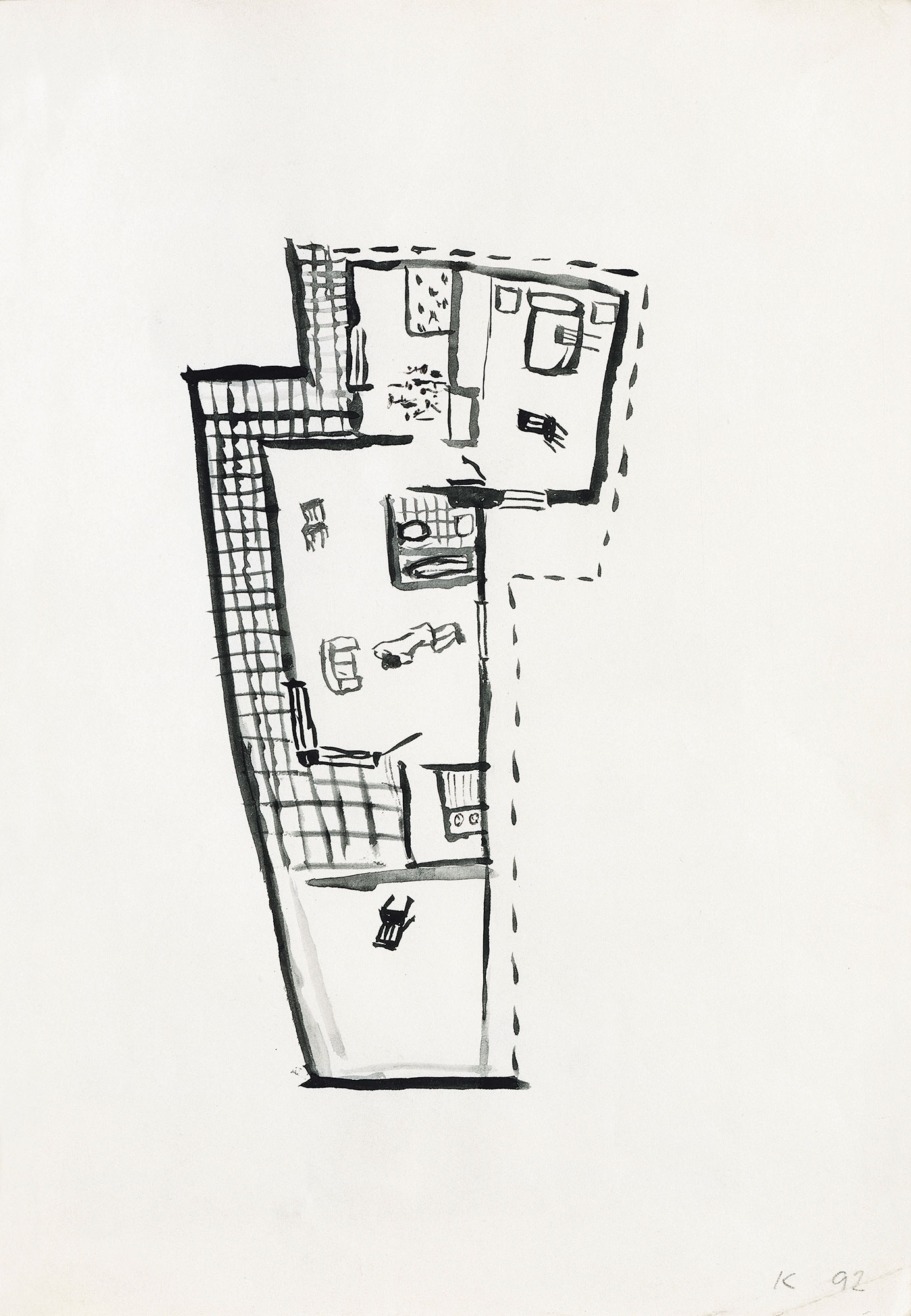

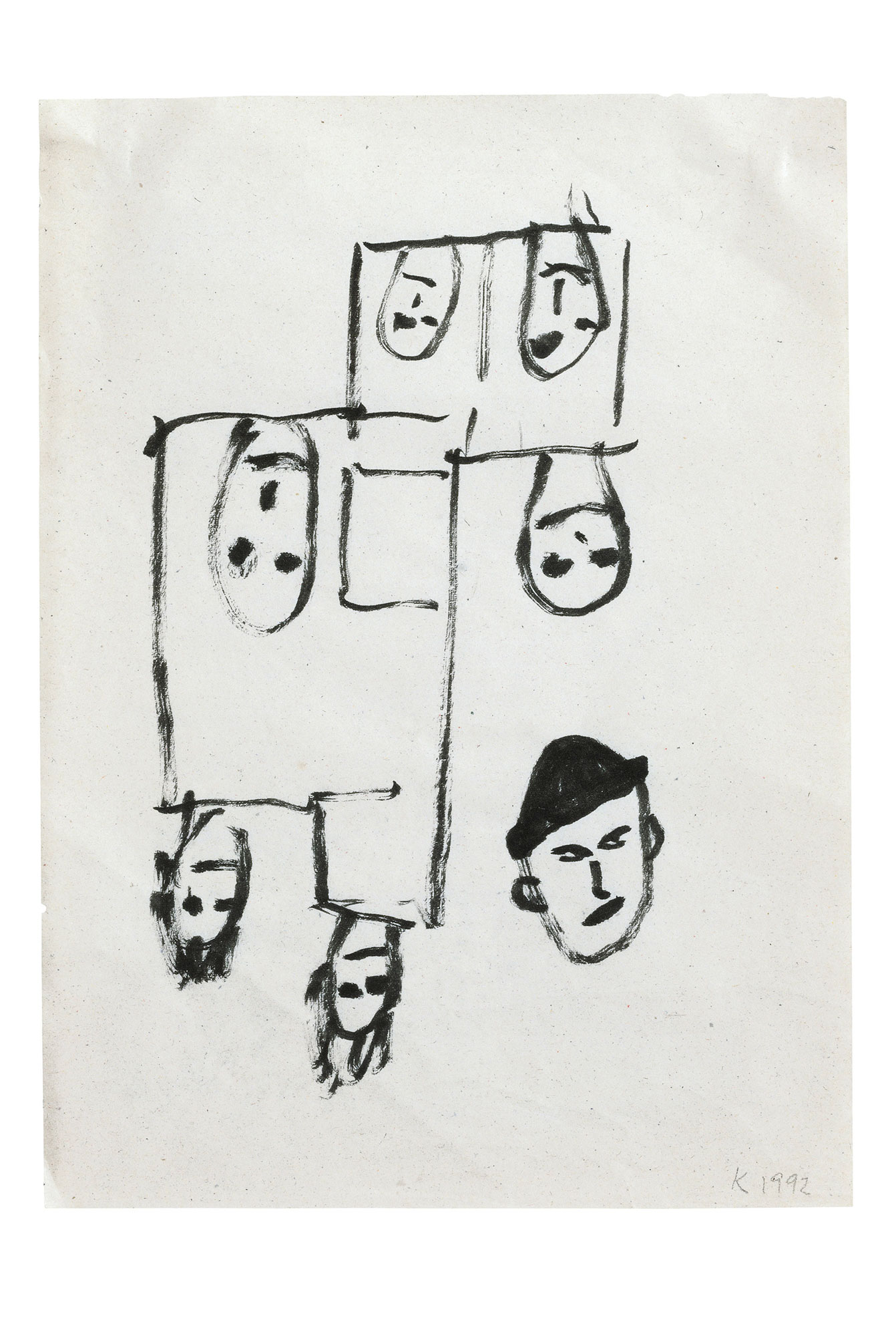

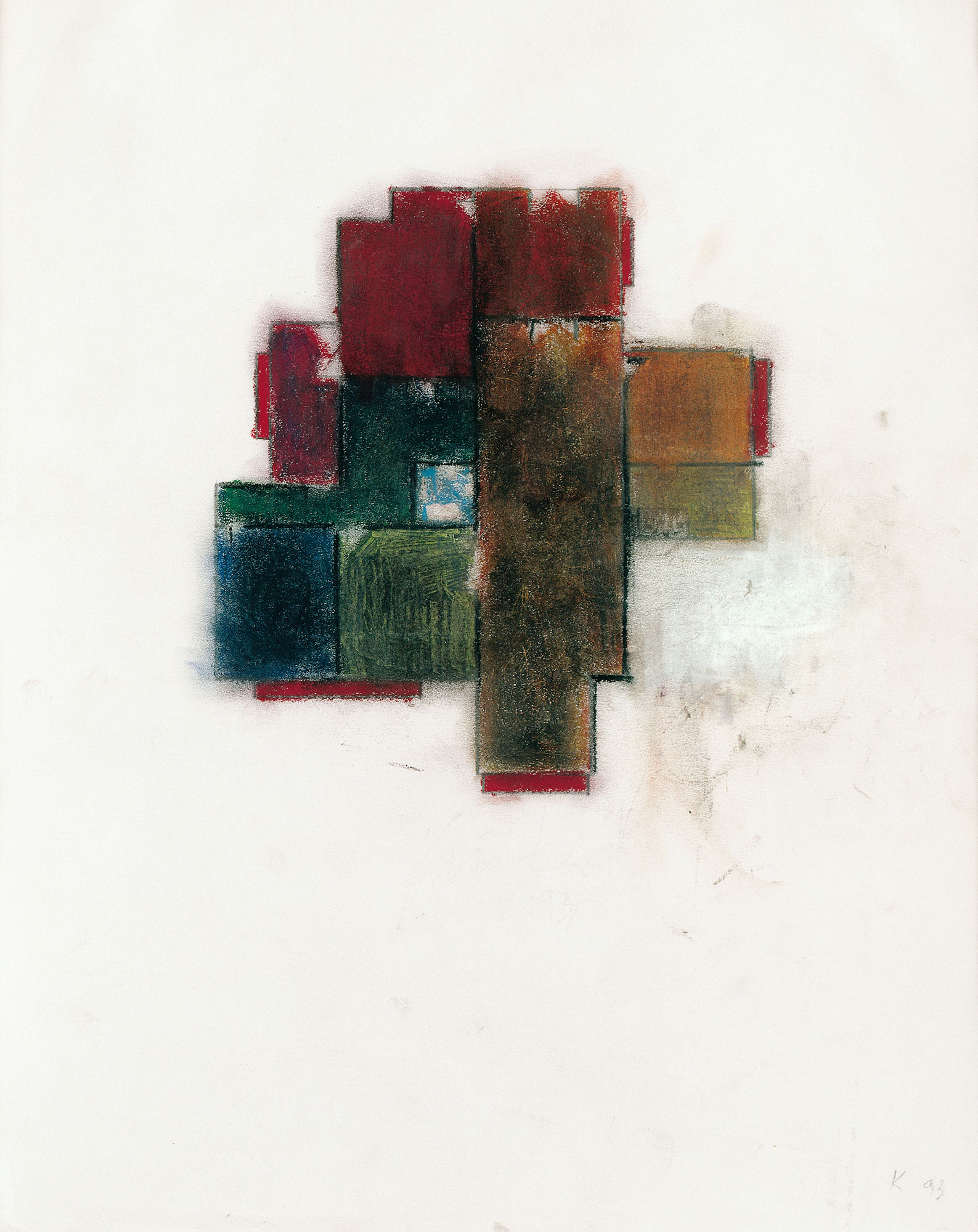

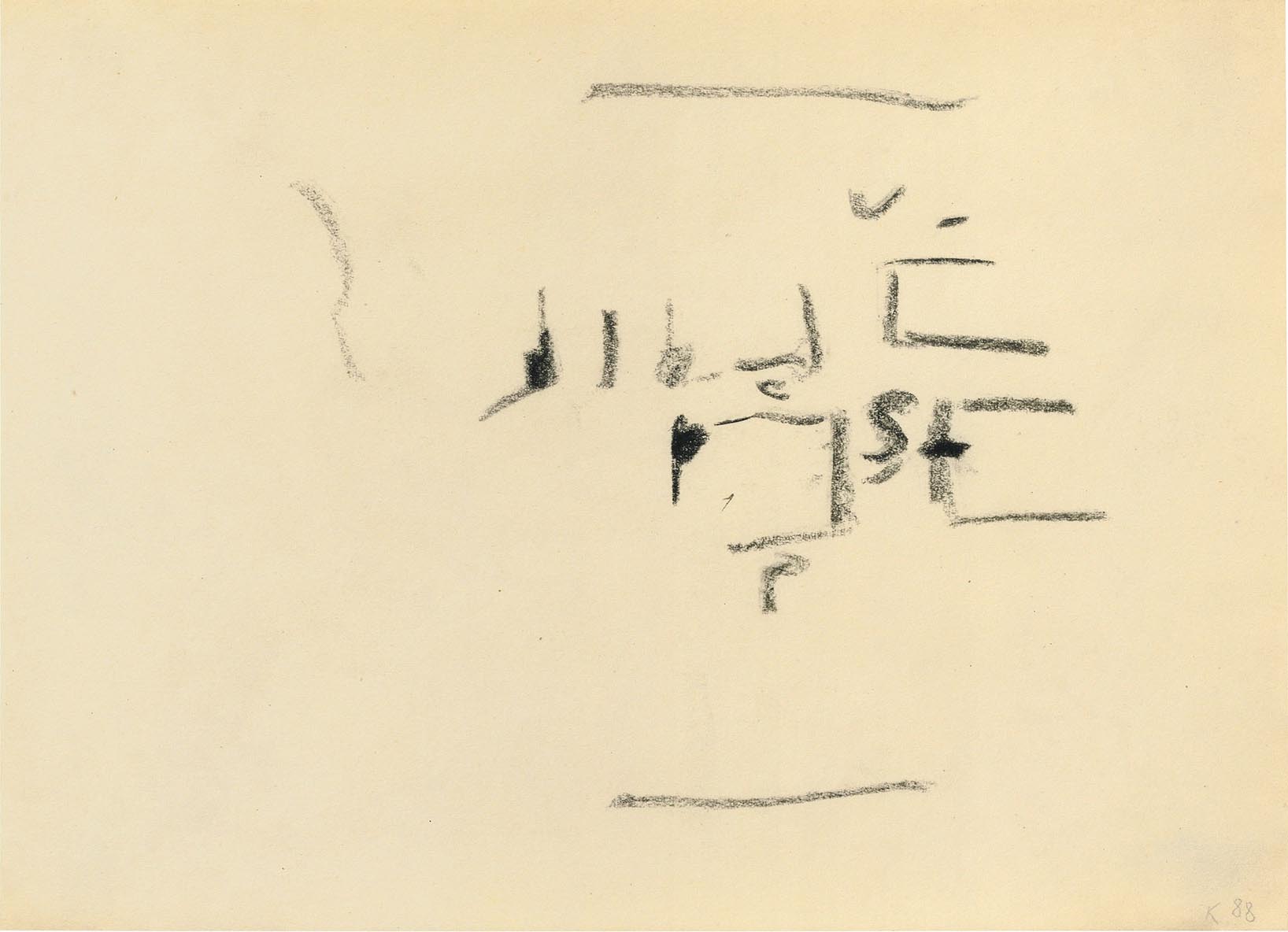

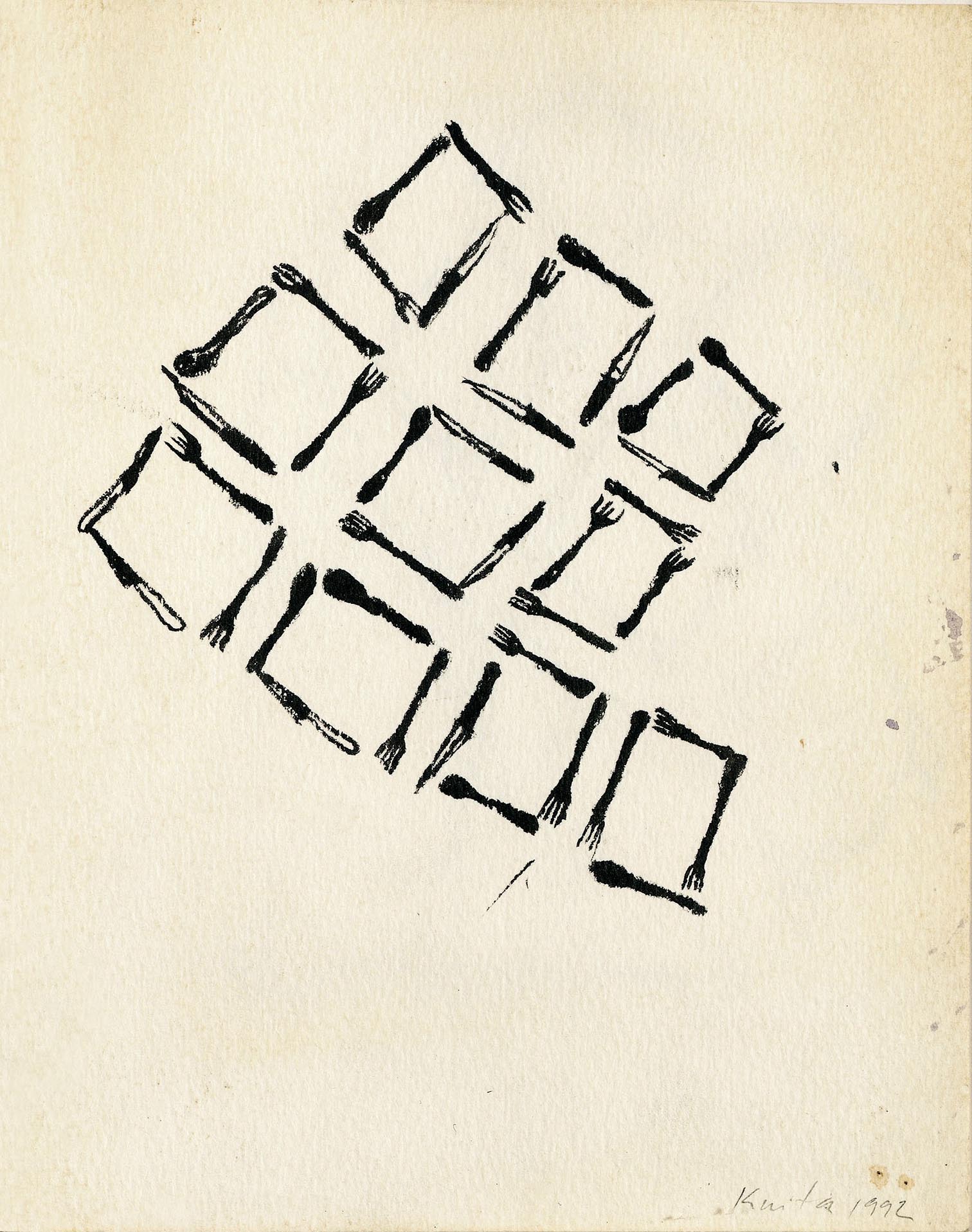

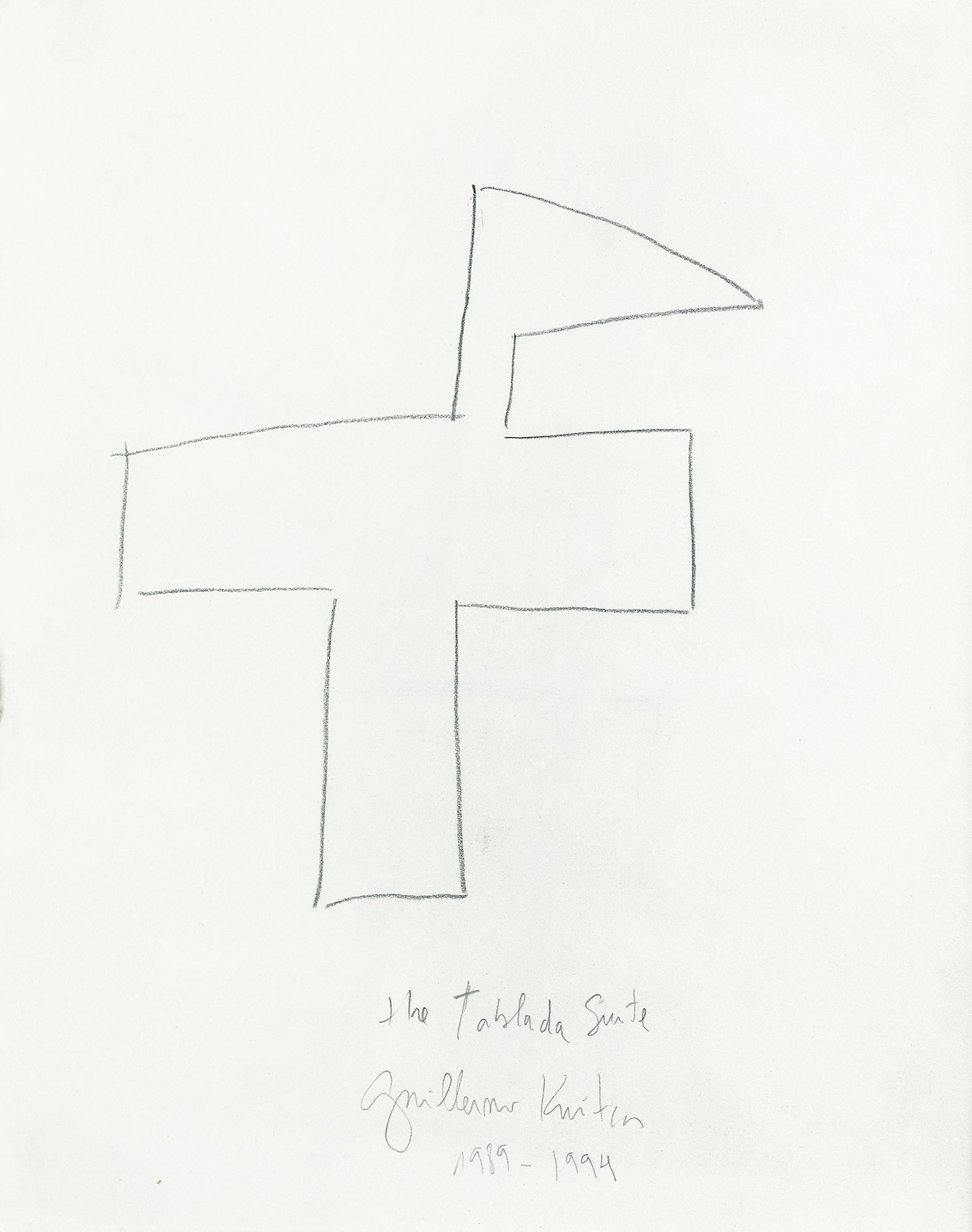

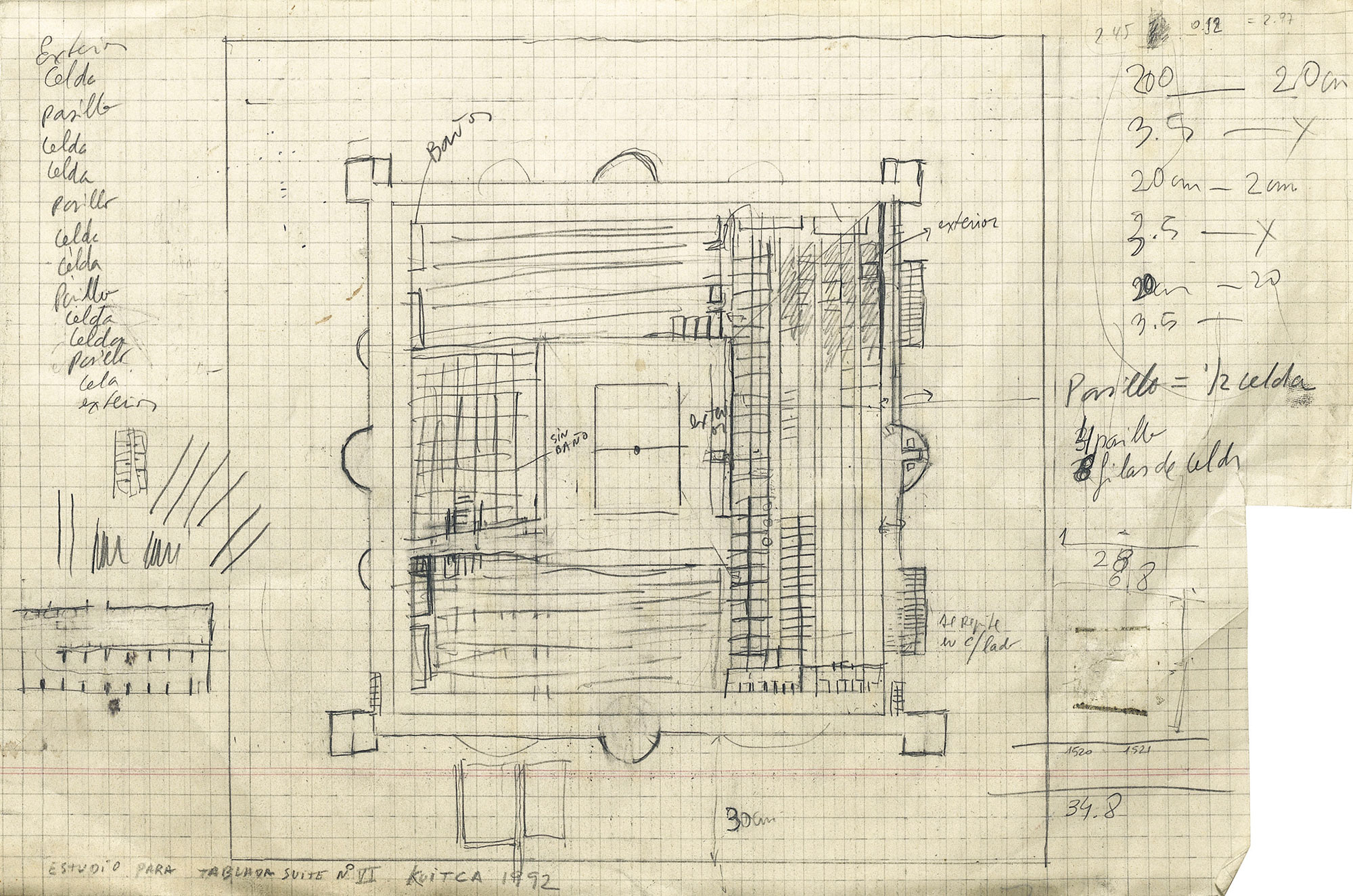

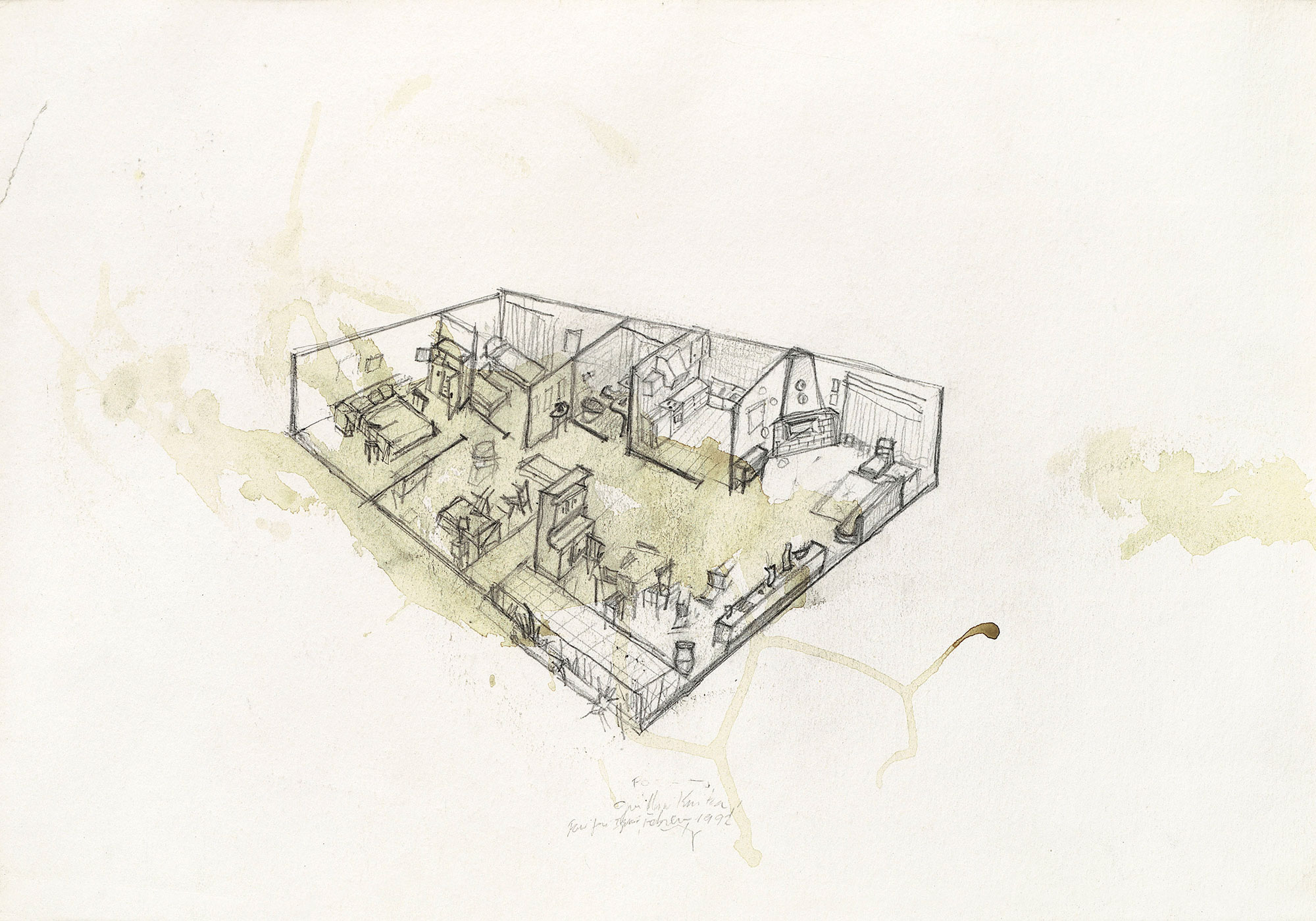

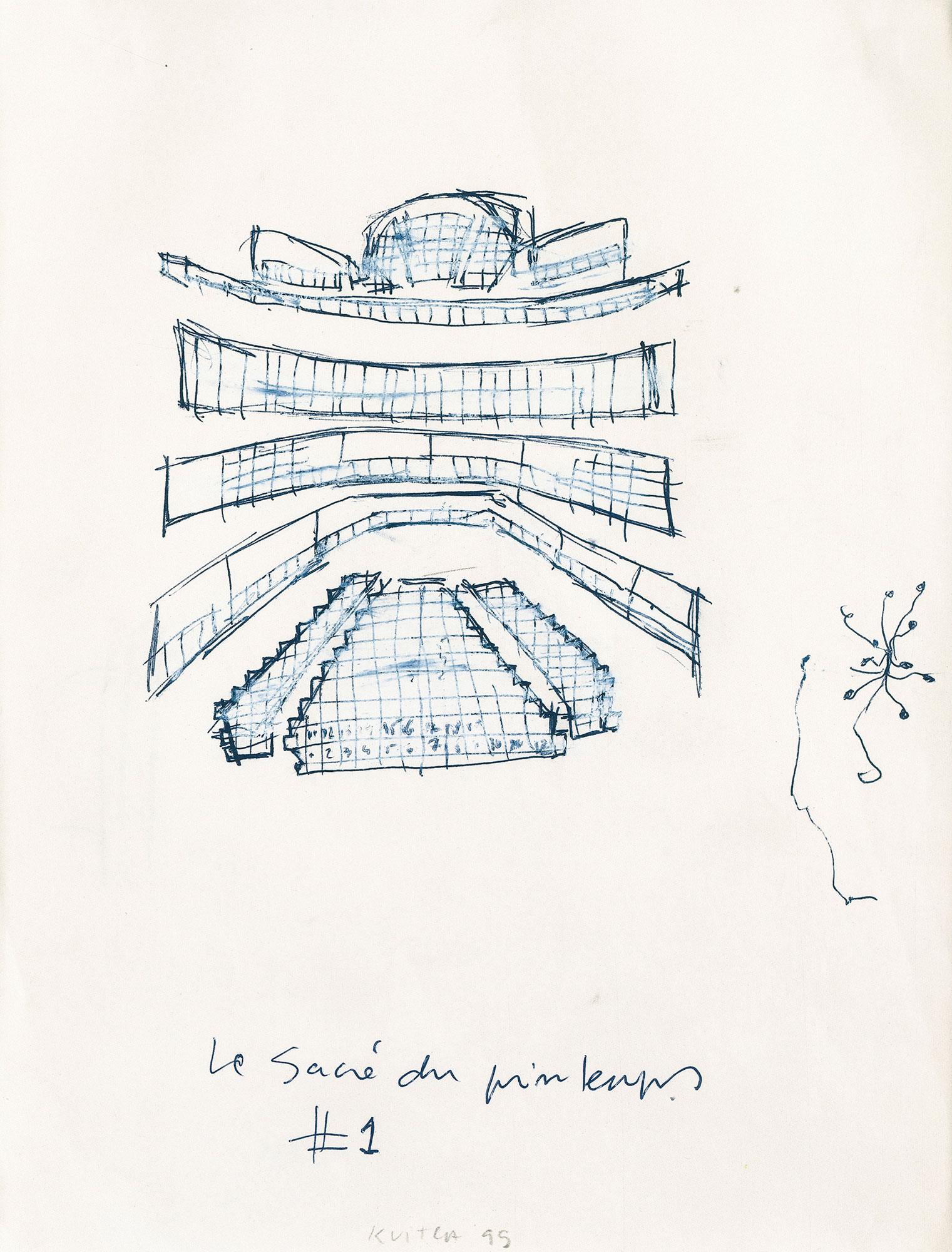

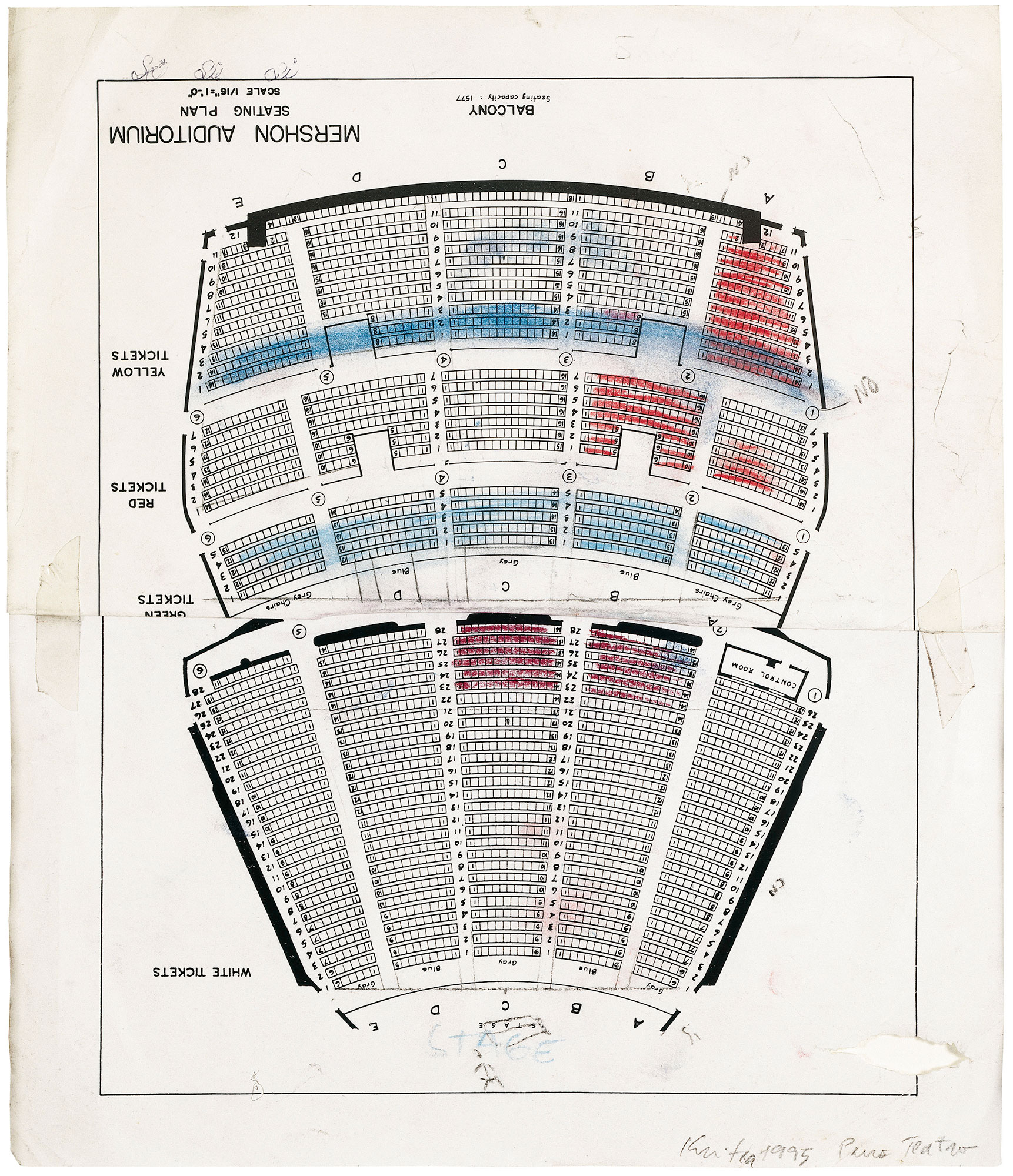

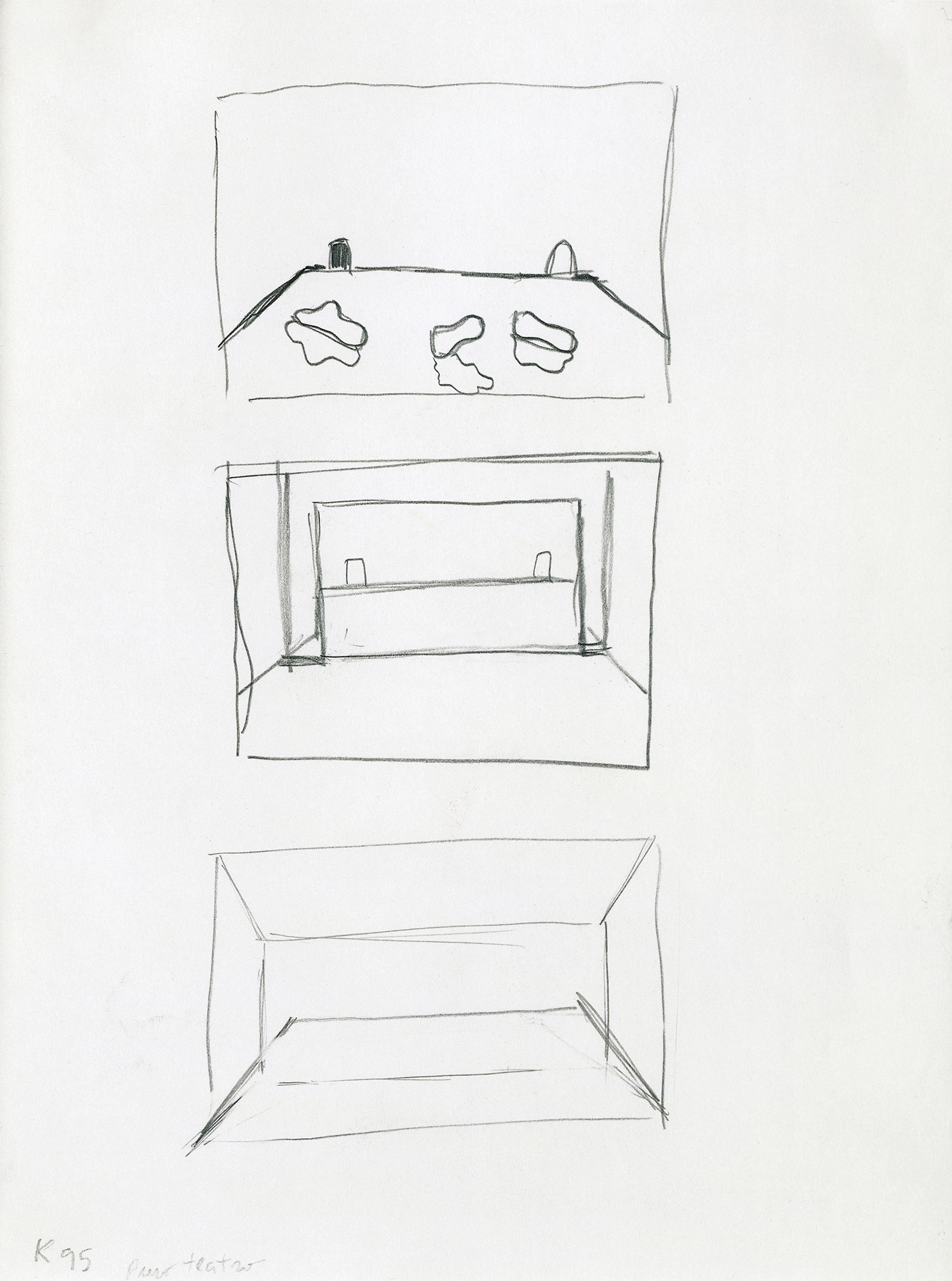

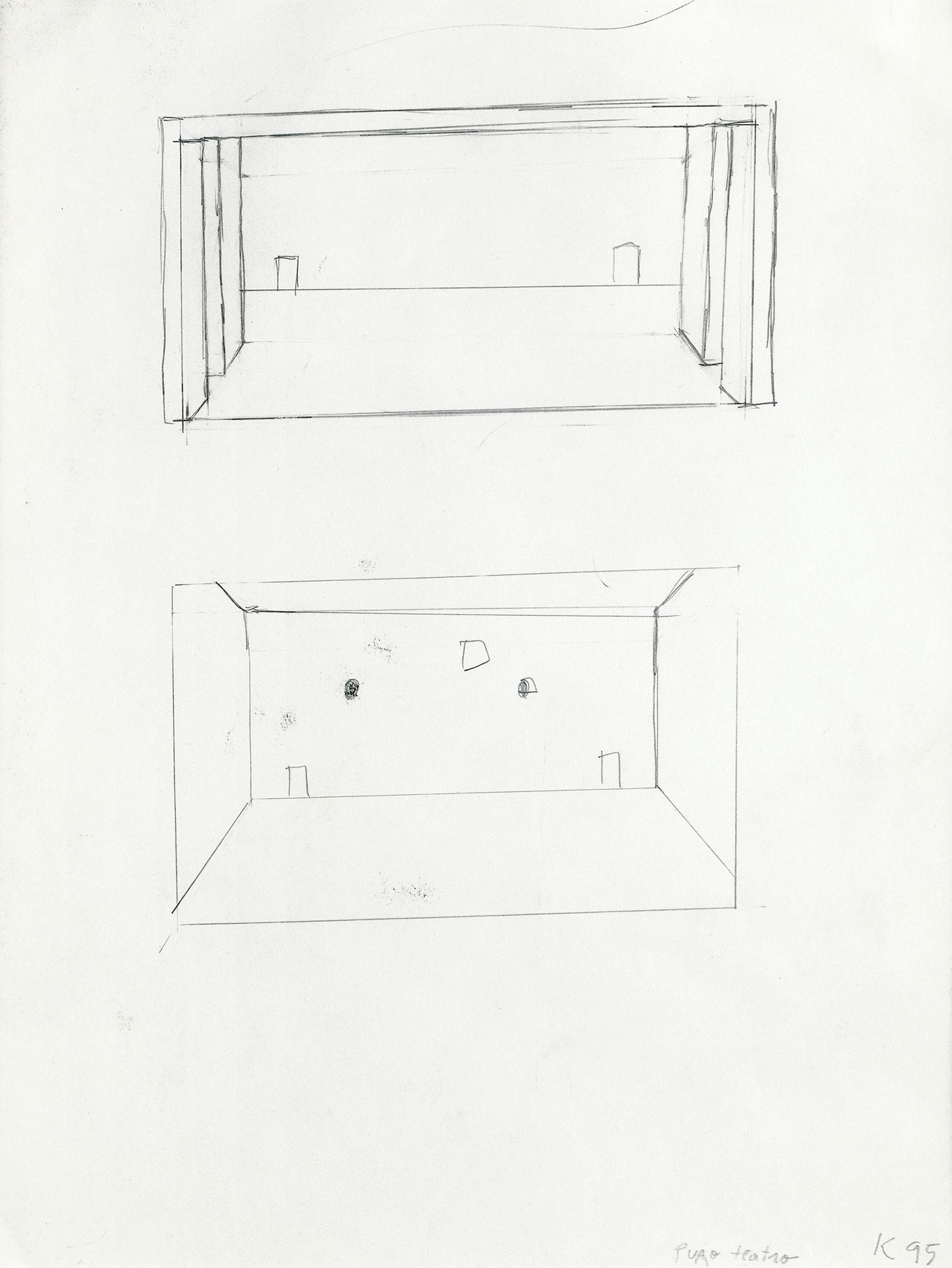

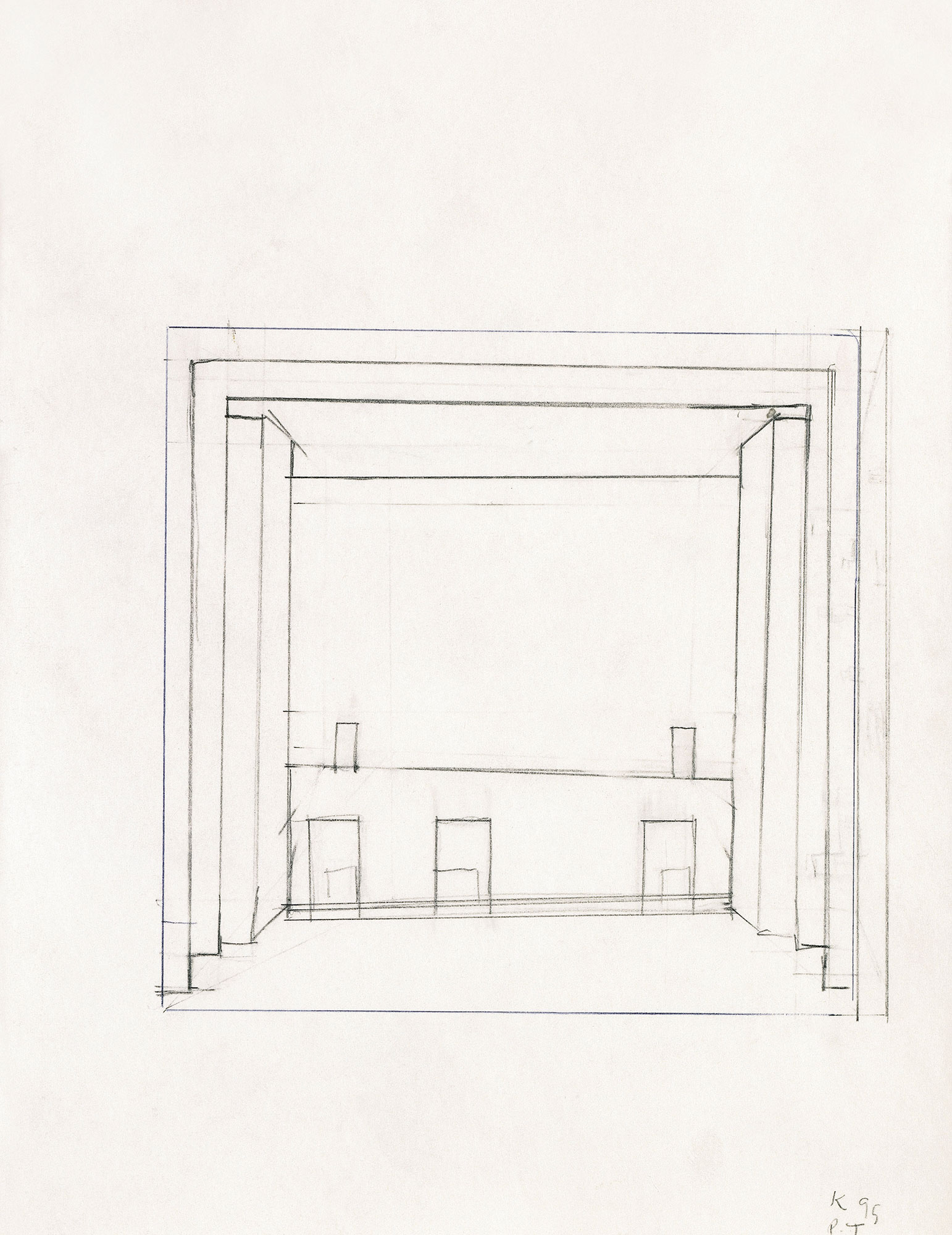

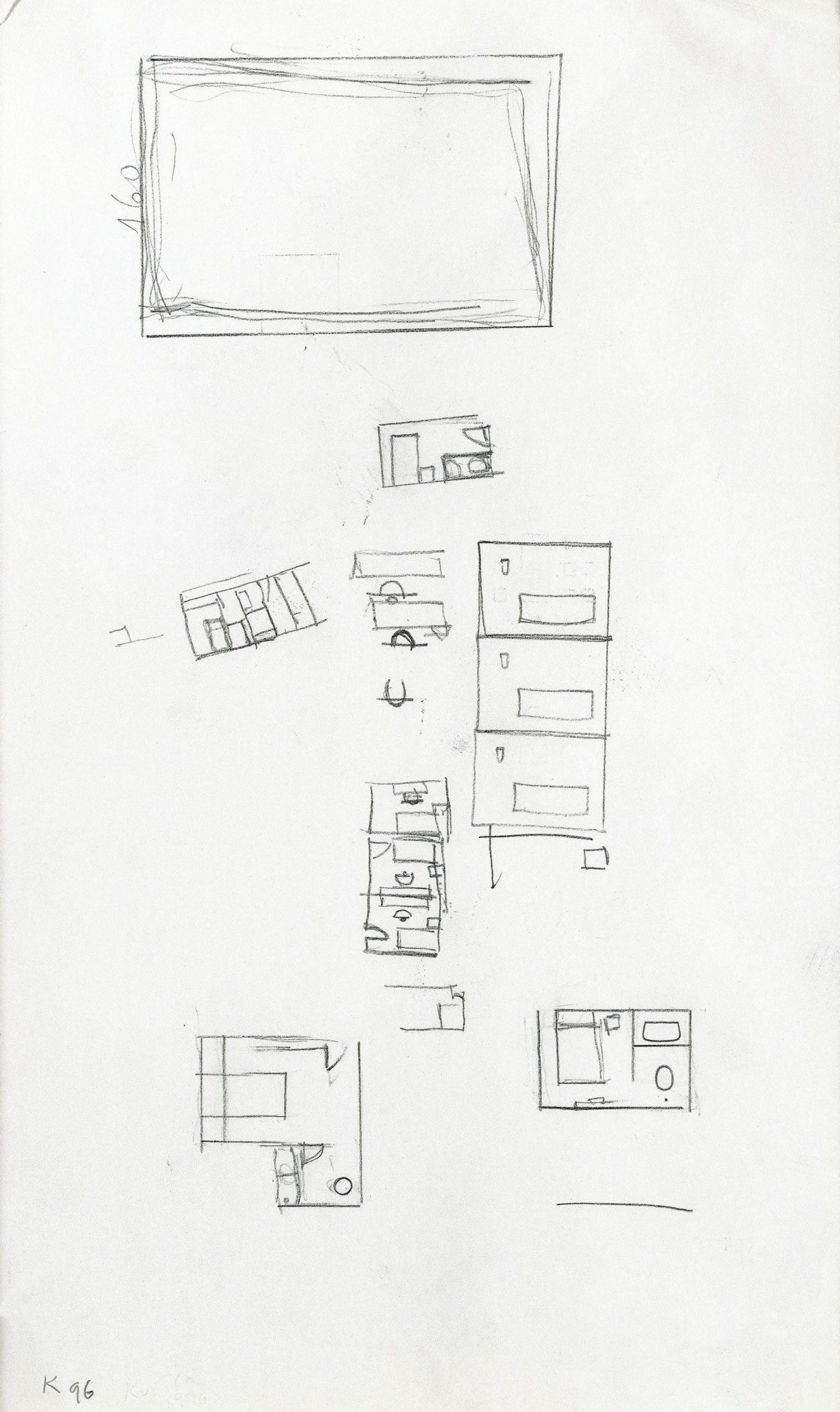

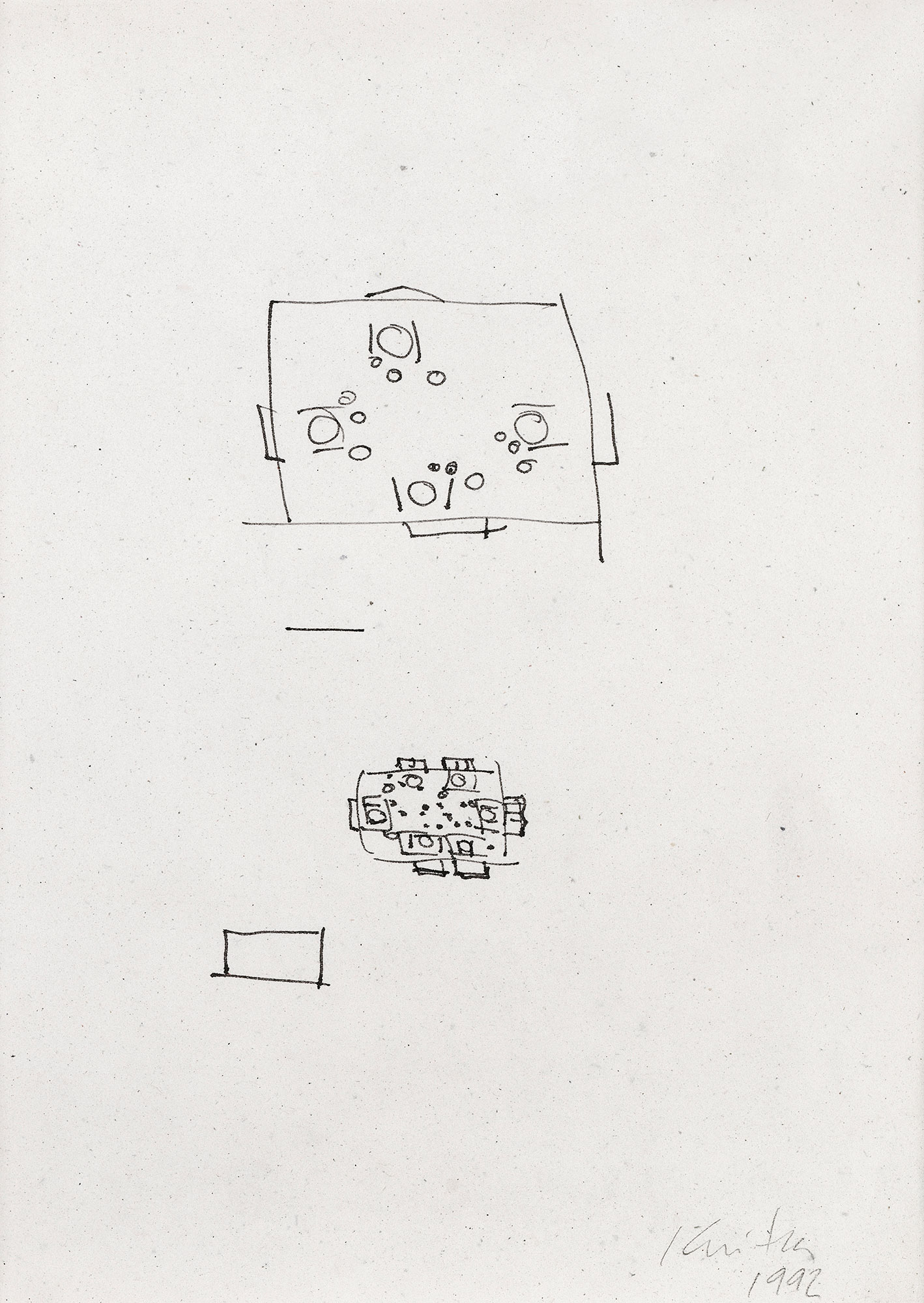

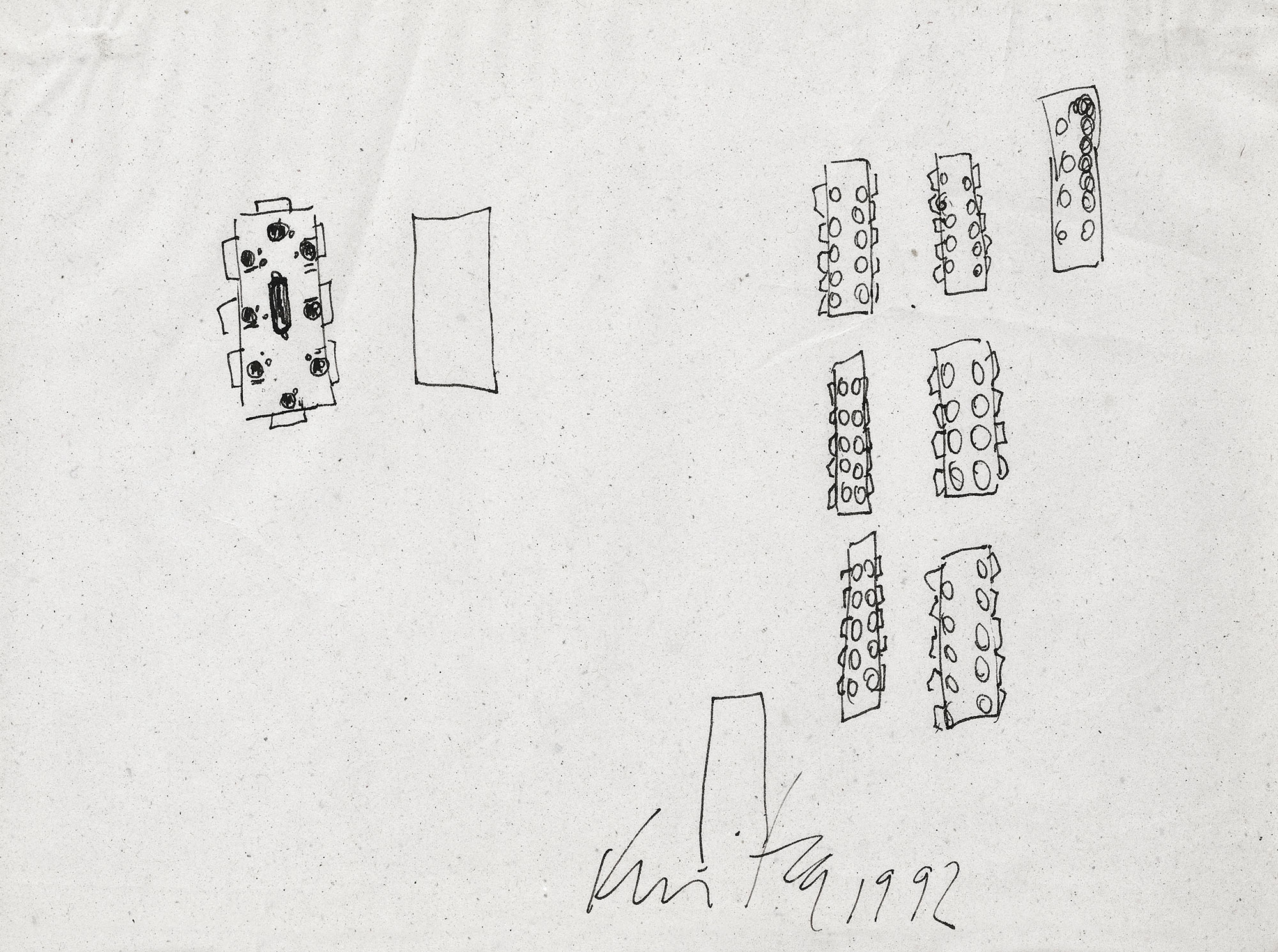

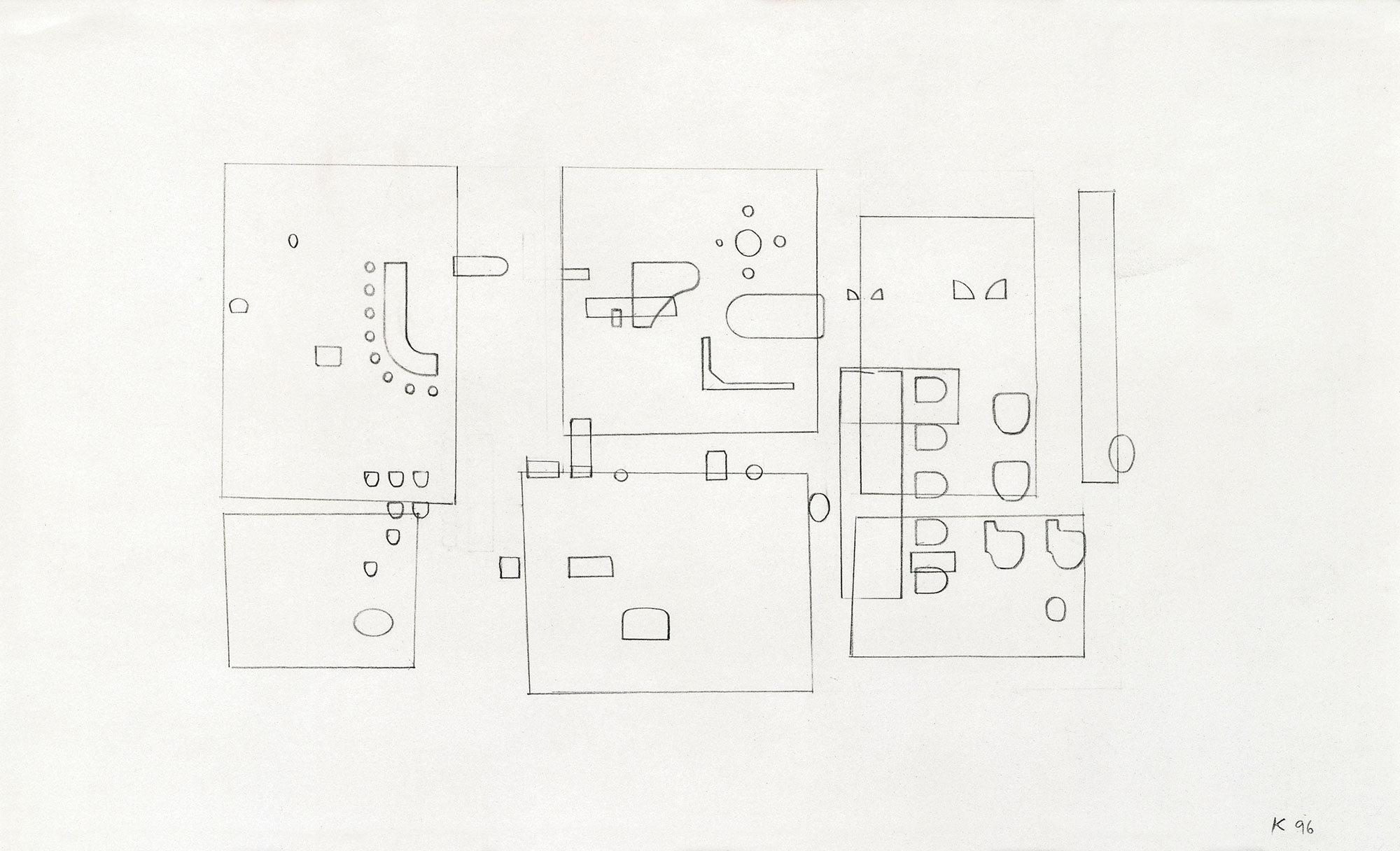

From that time to the present, his work has undergone several successive shifts, organized in series defined by very clear parameters. The most important of these series date from the 1980s, and they are stage sets, maps, architectural plans and, most recently, his “cubist” works: the artist realizes all of these works by adopting a highly codified language—such as technical drawing, for example—that he develops and expands in an infinite number of variations.

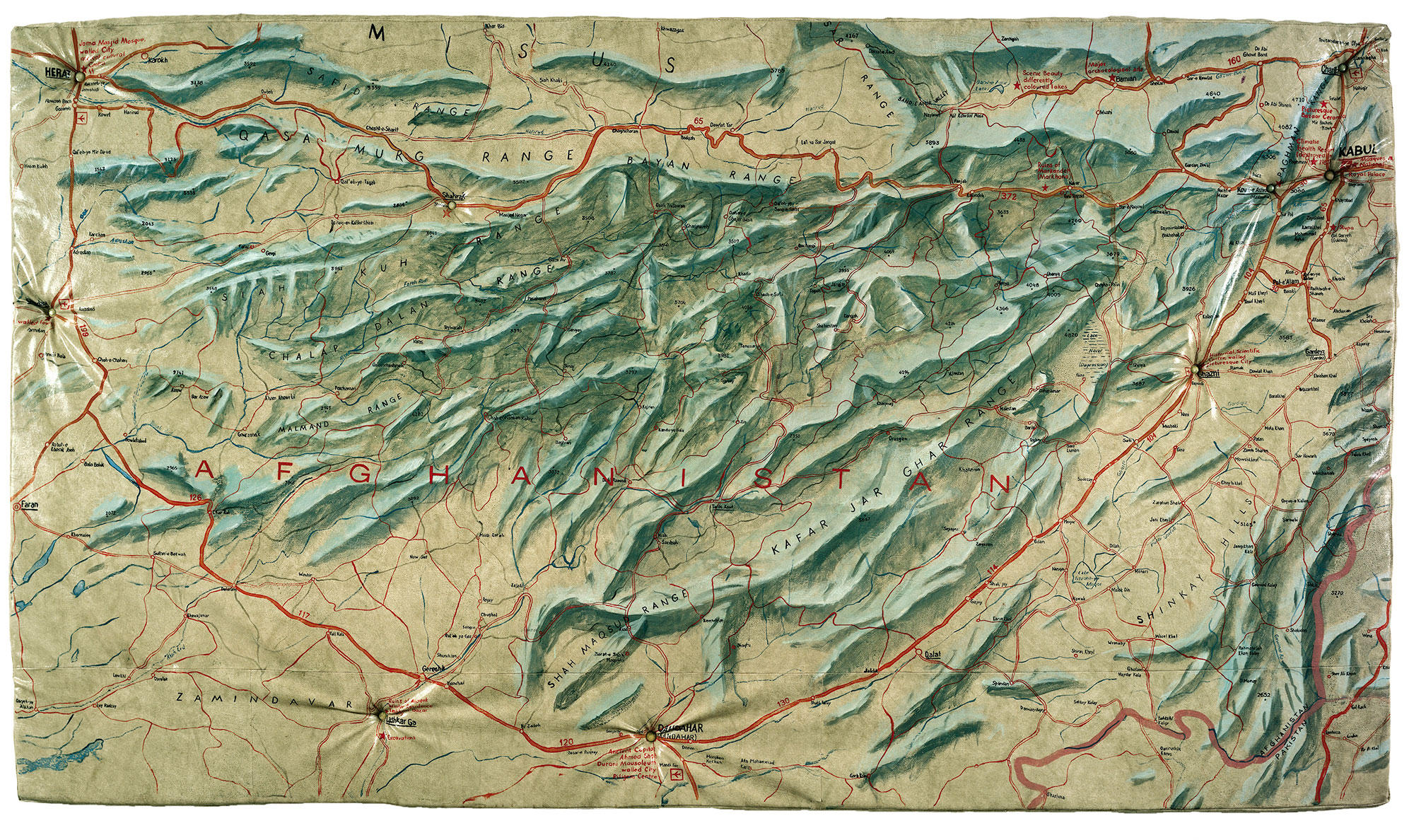

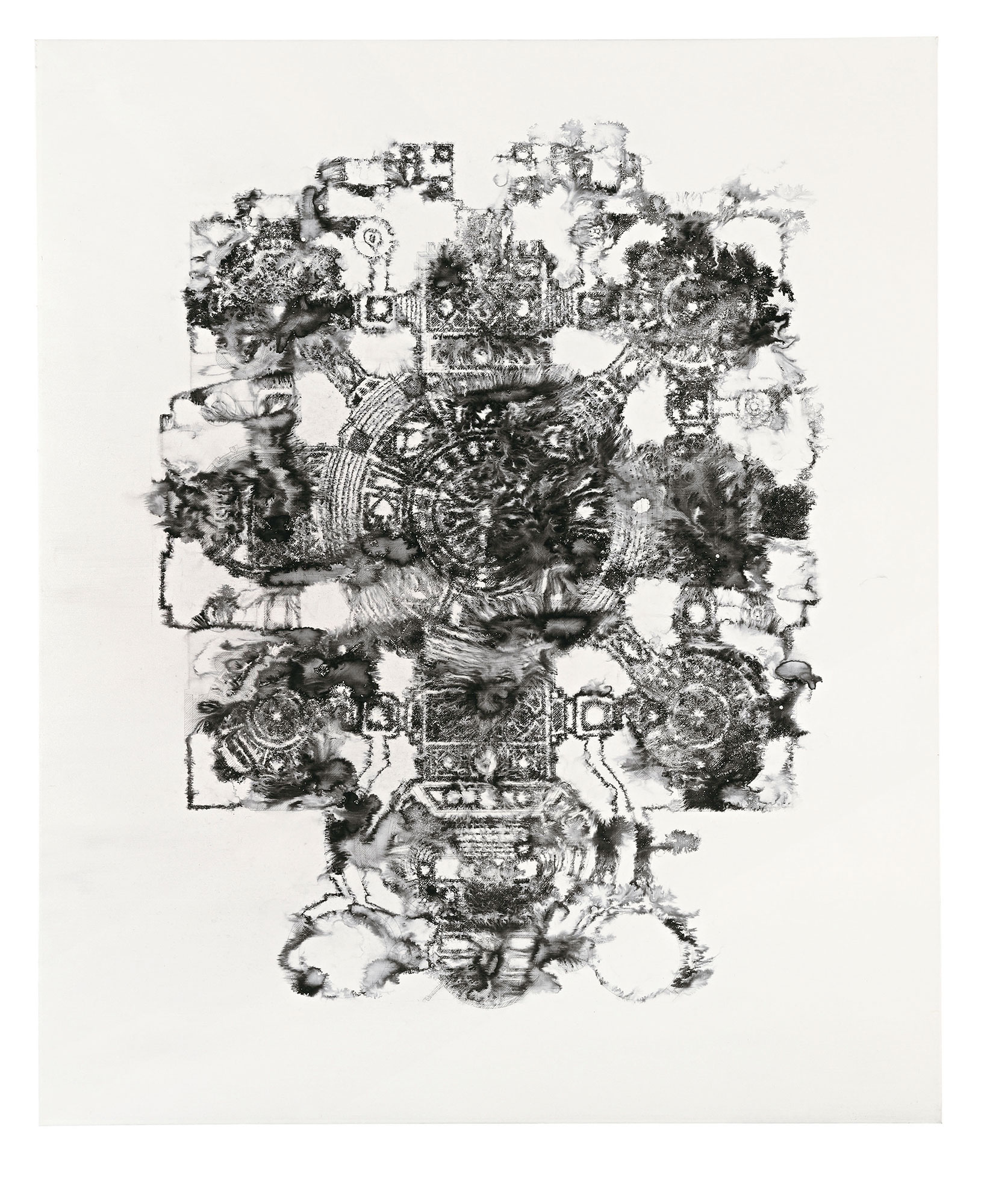

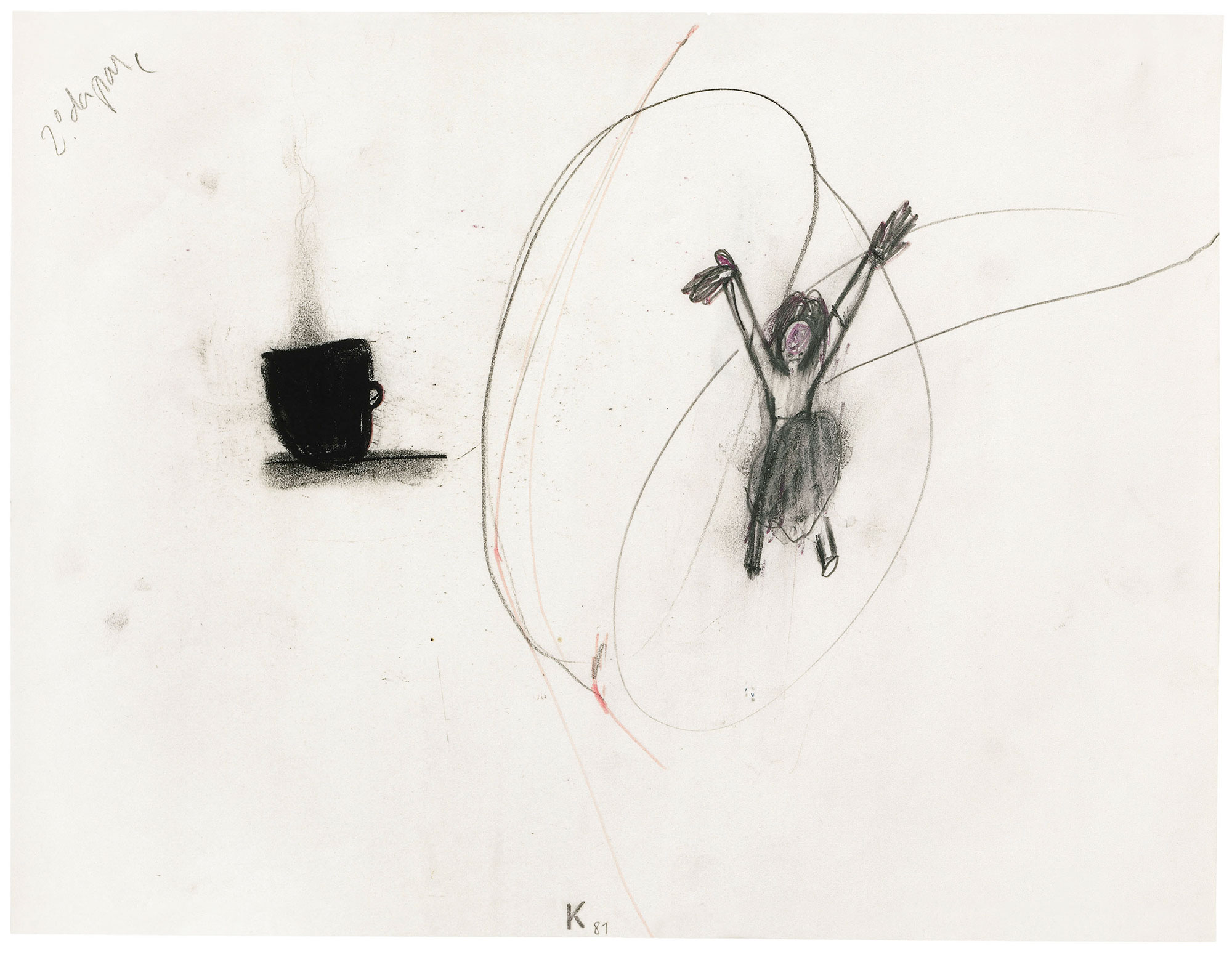

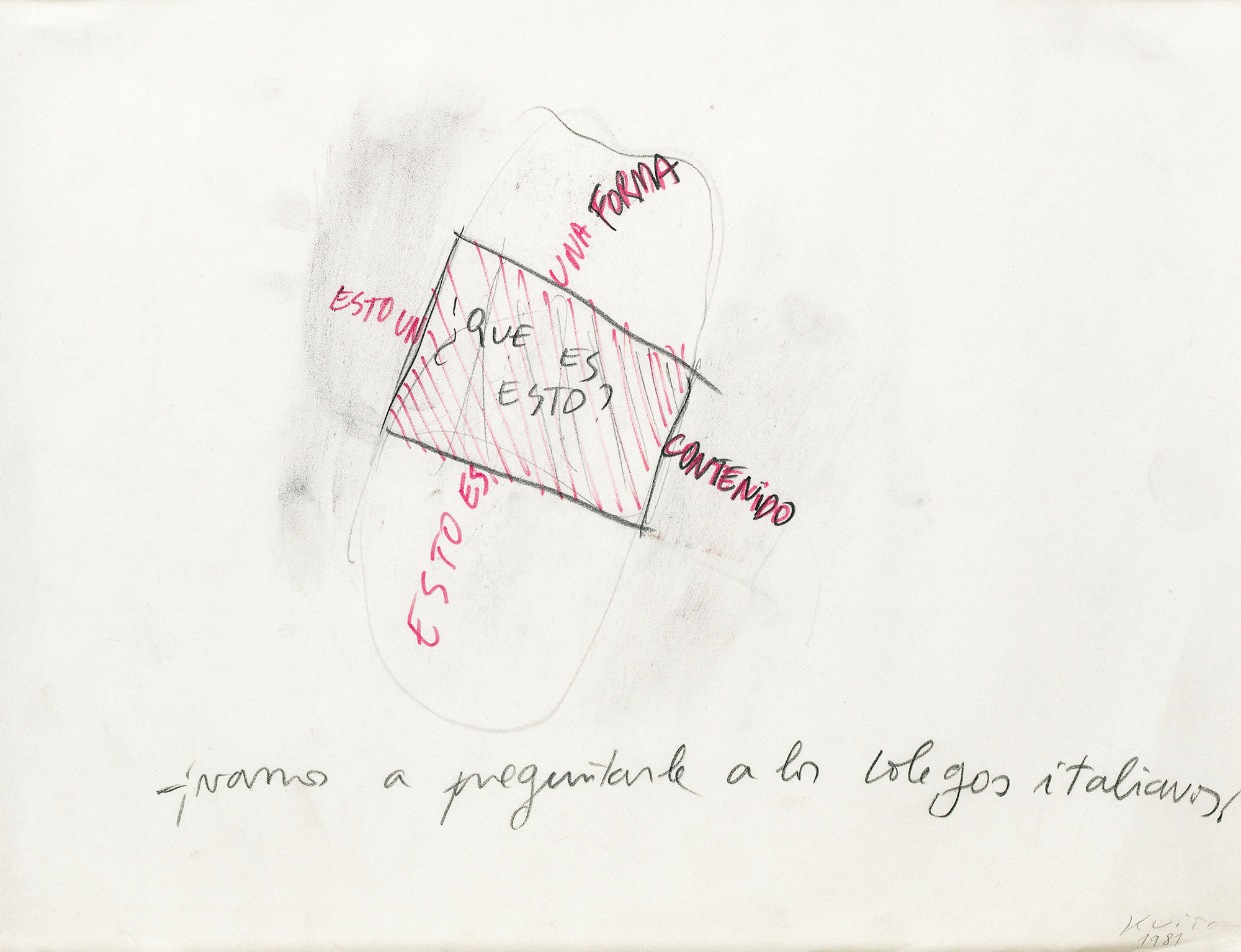

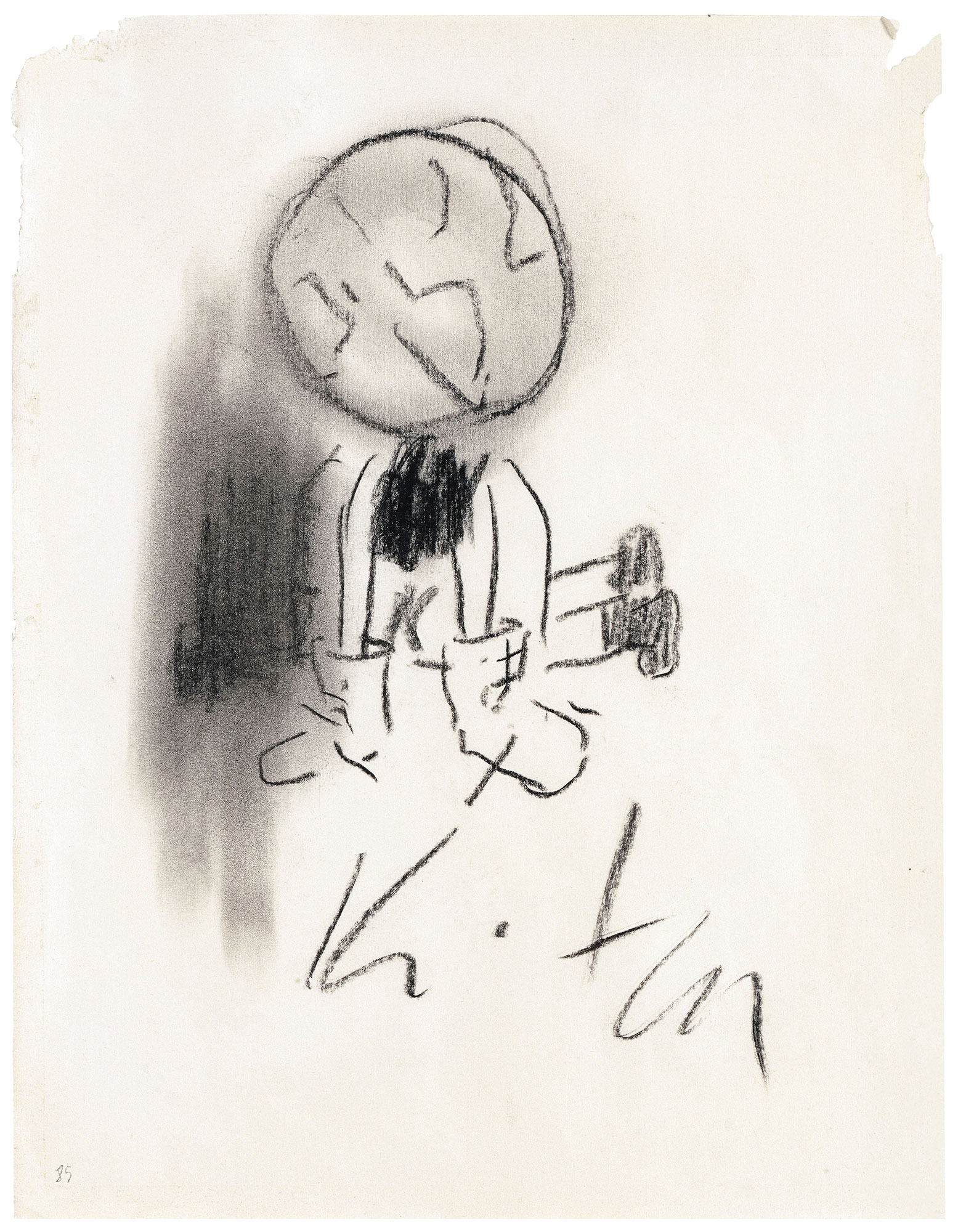

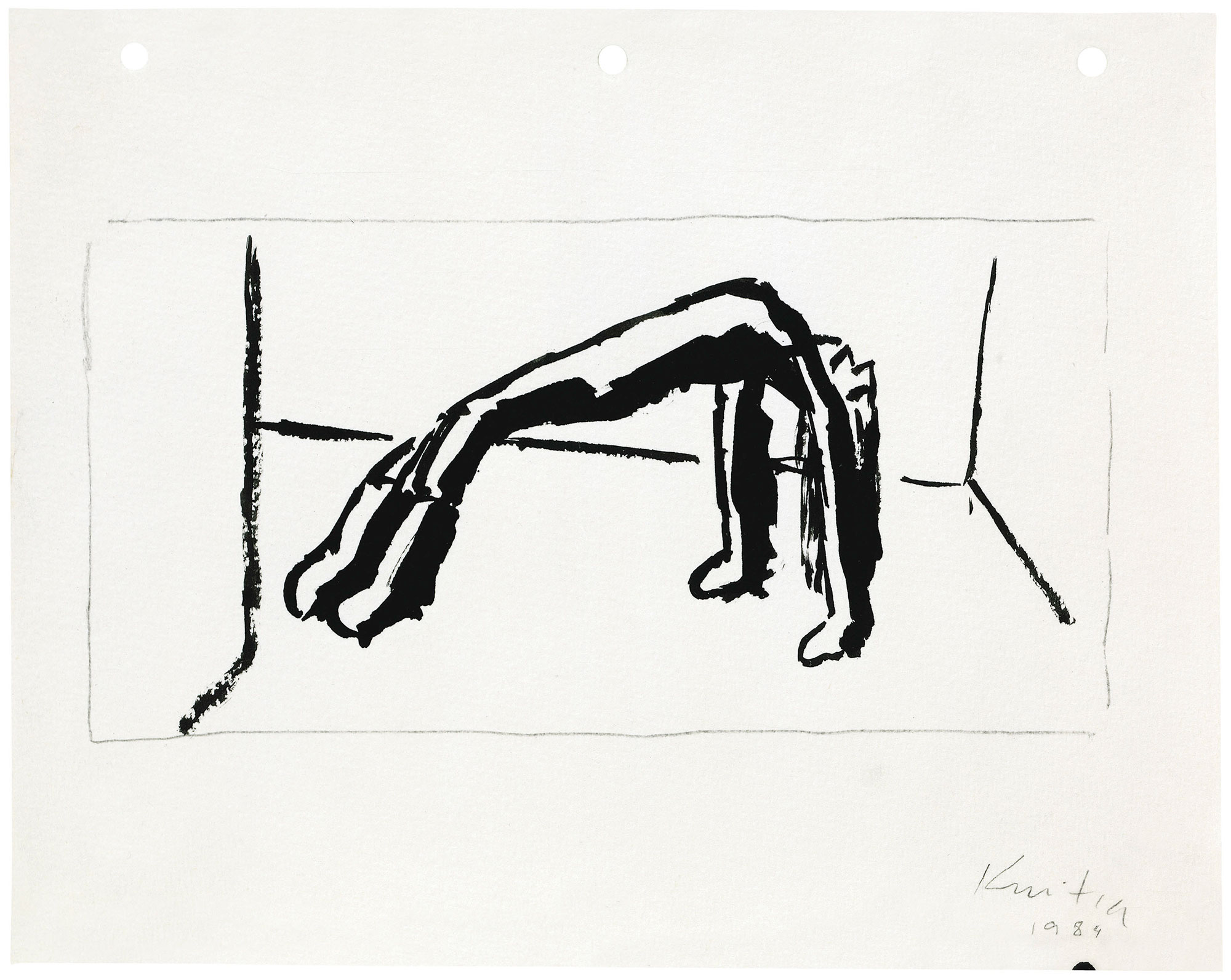

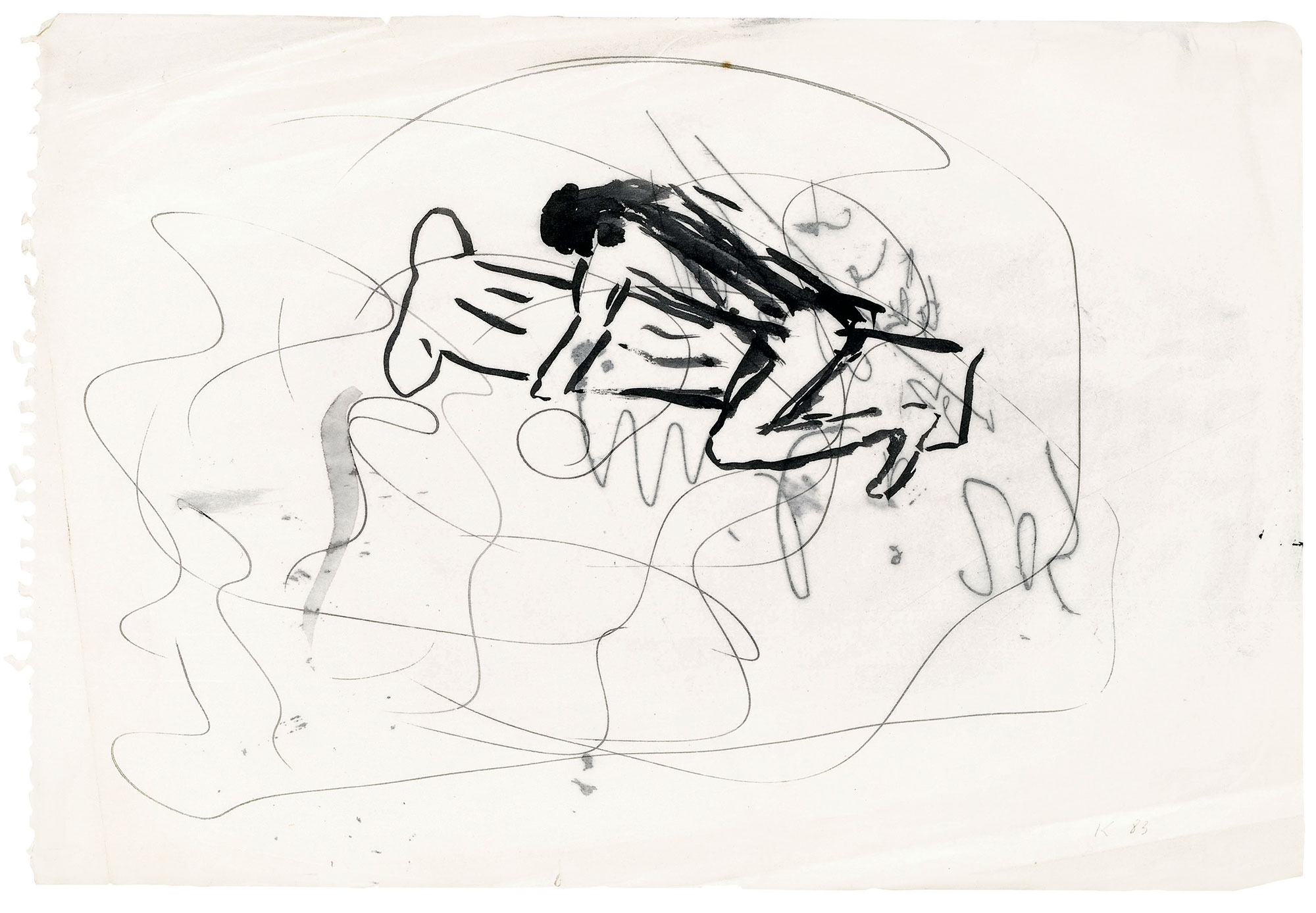

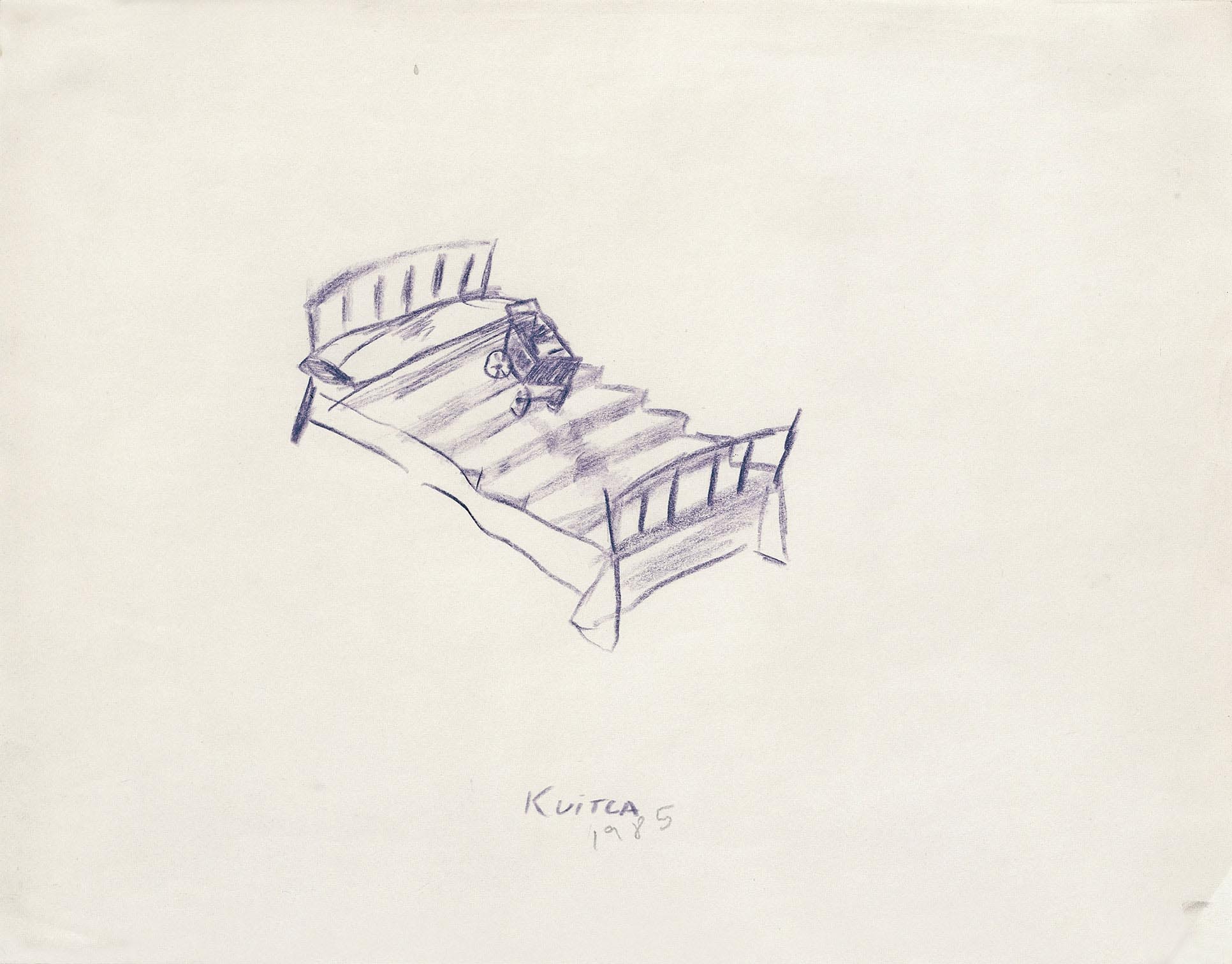

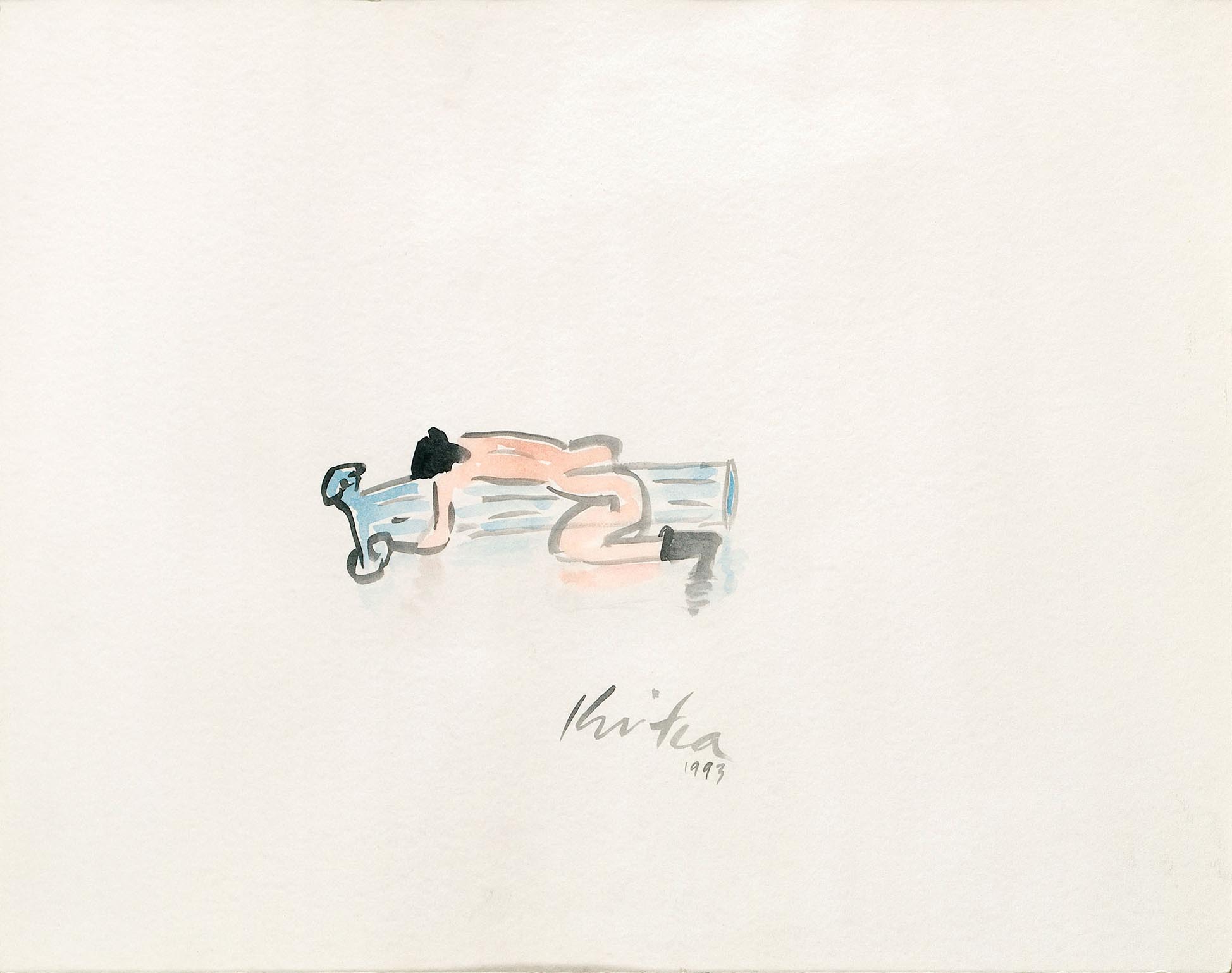

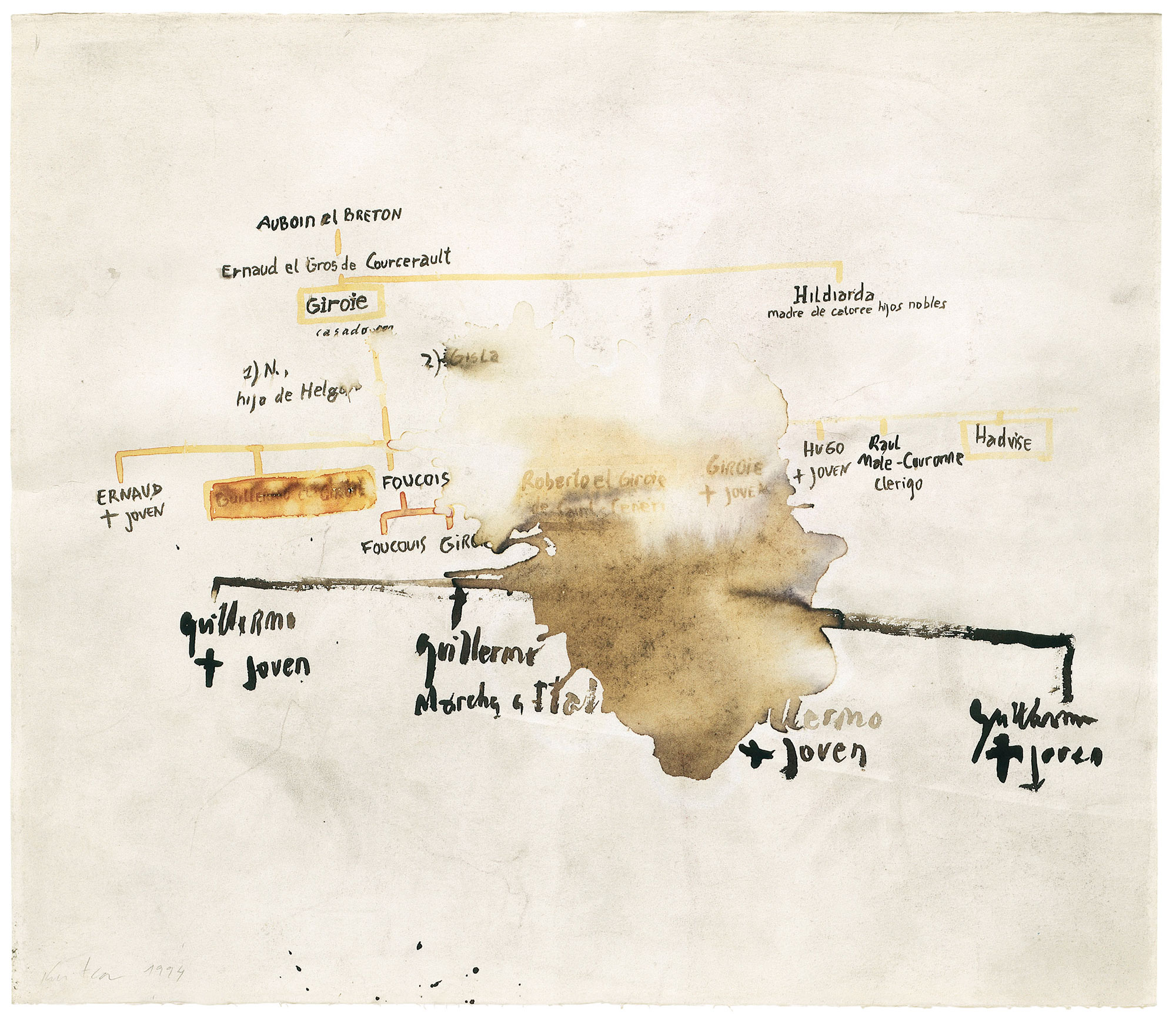

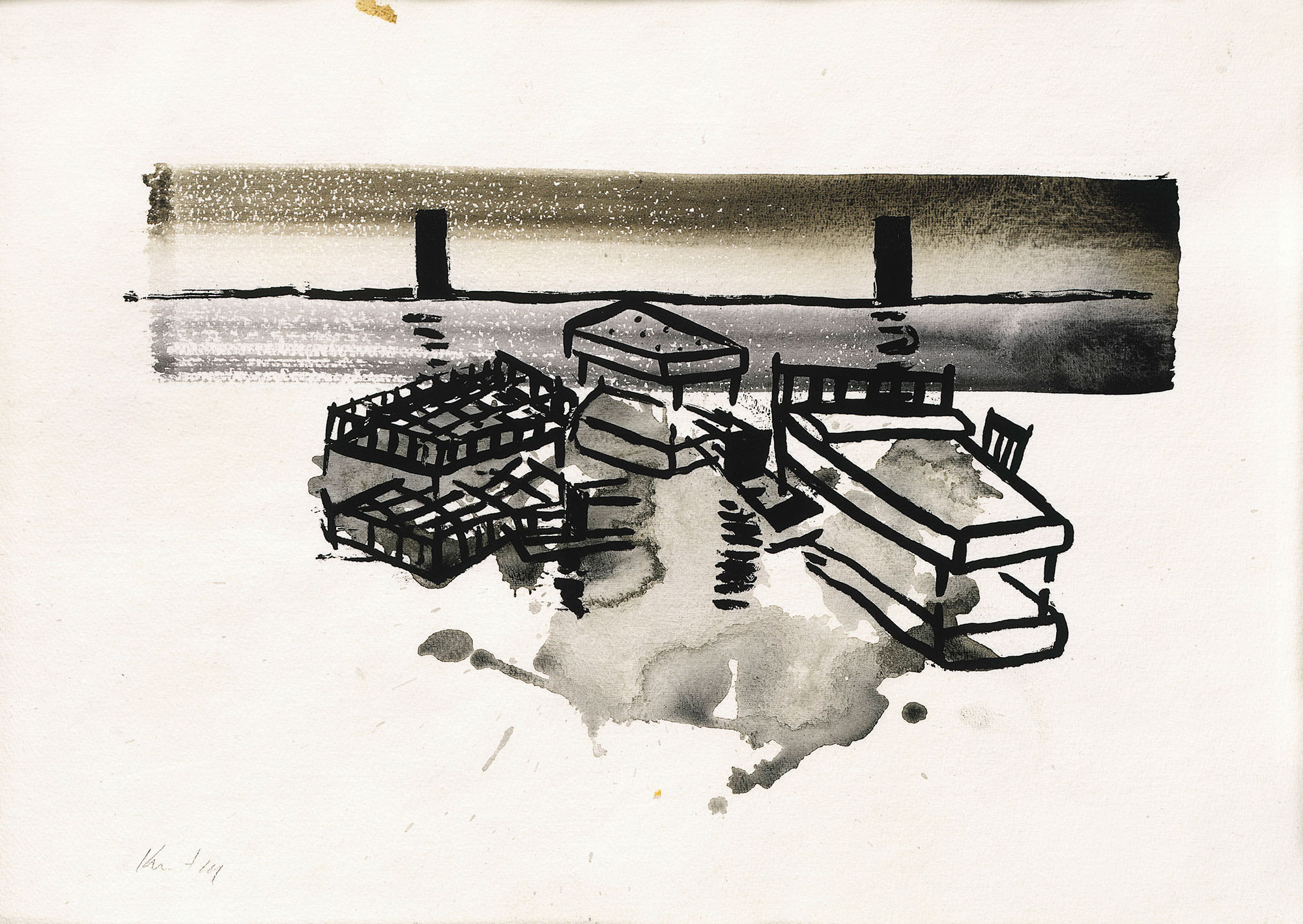

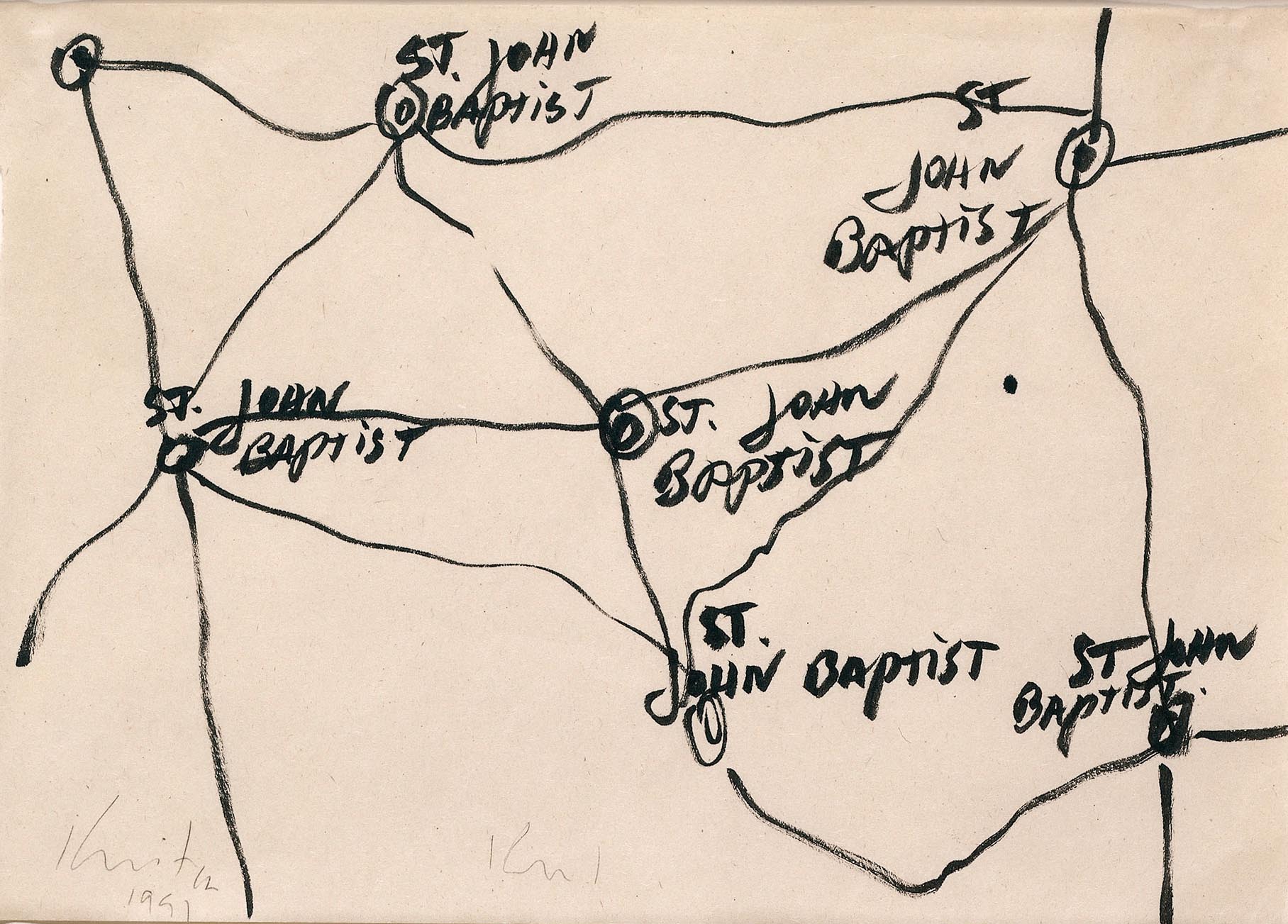

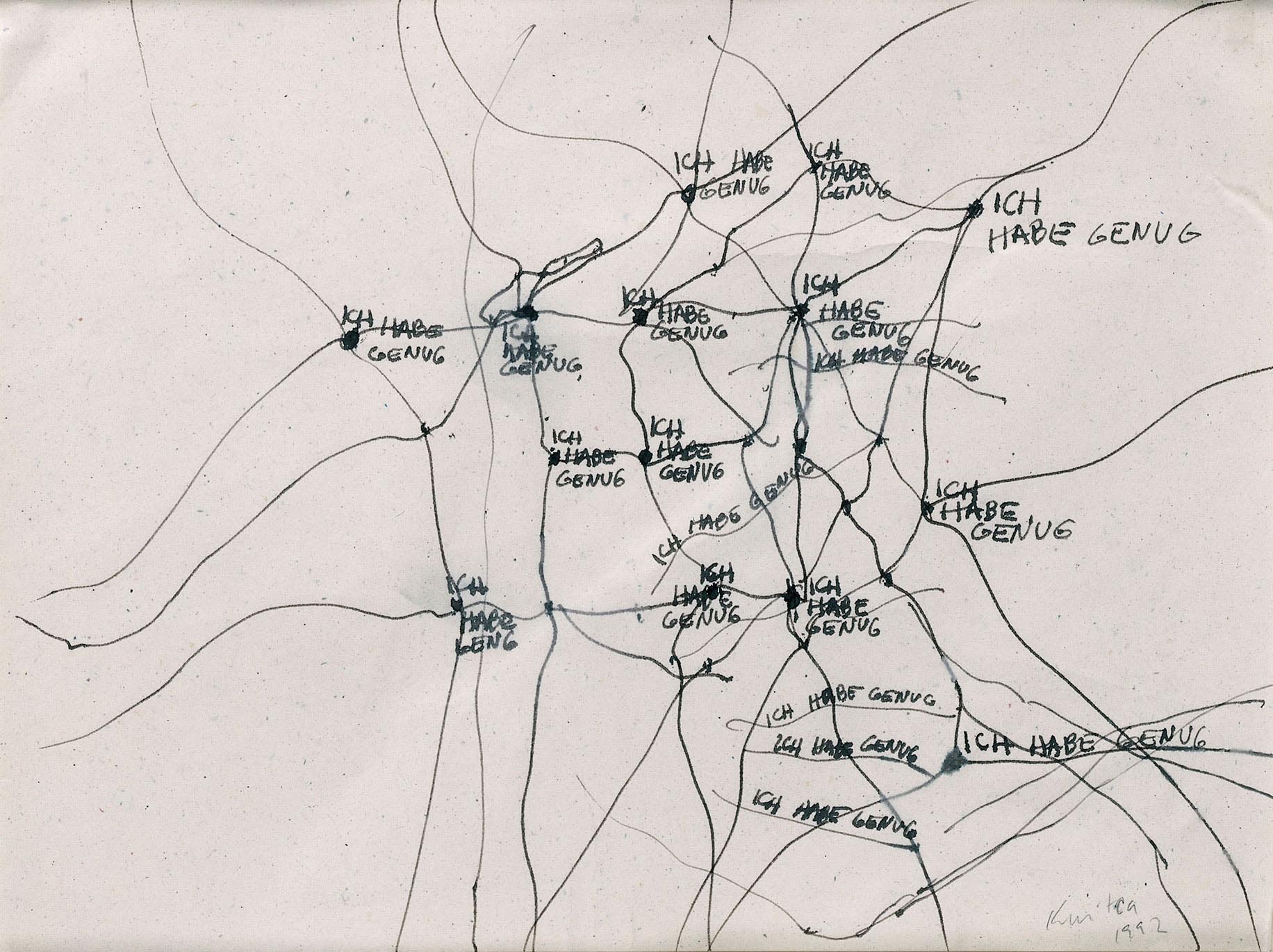

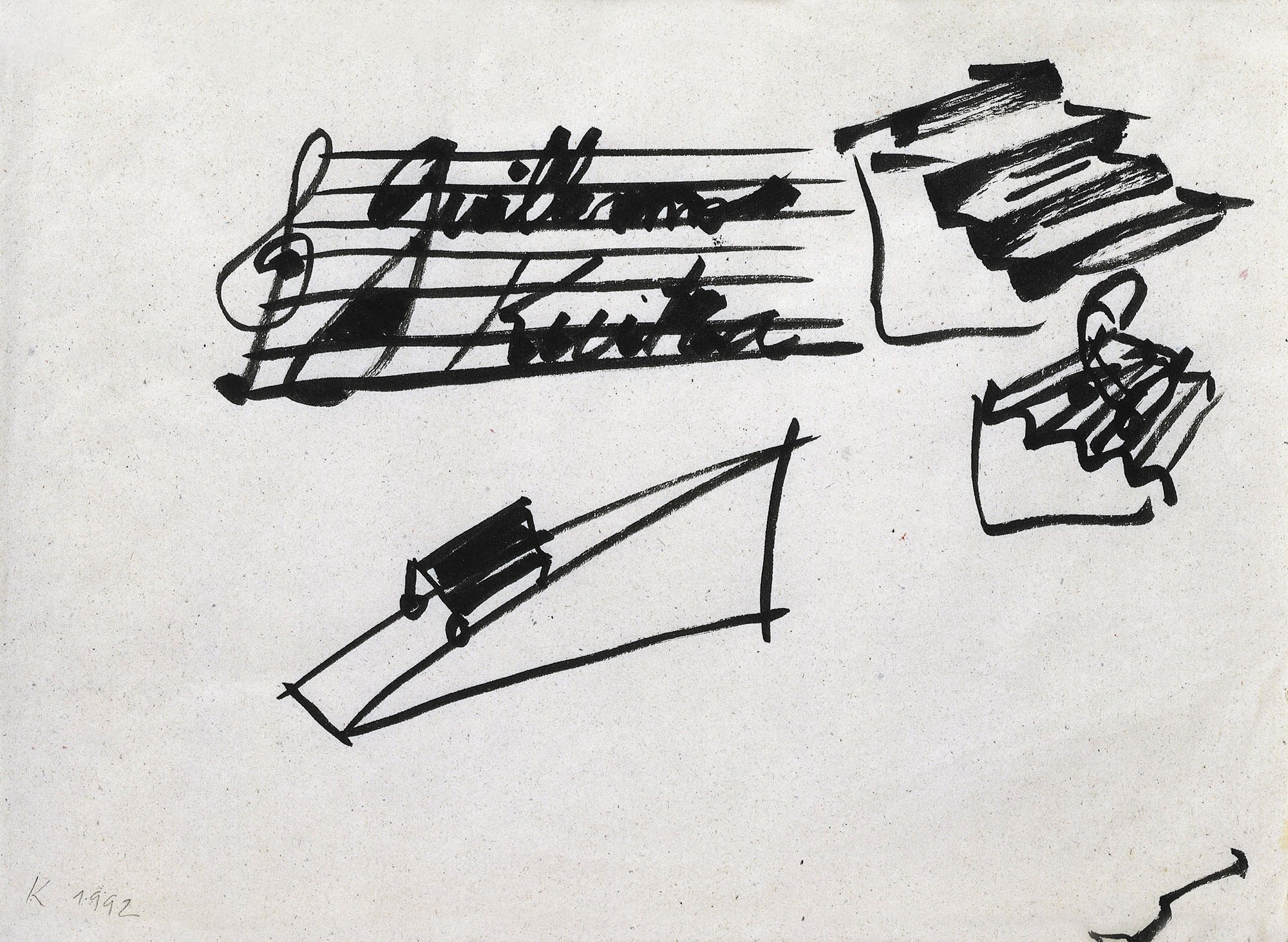

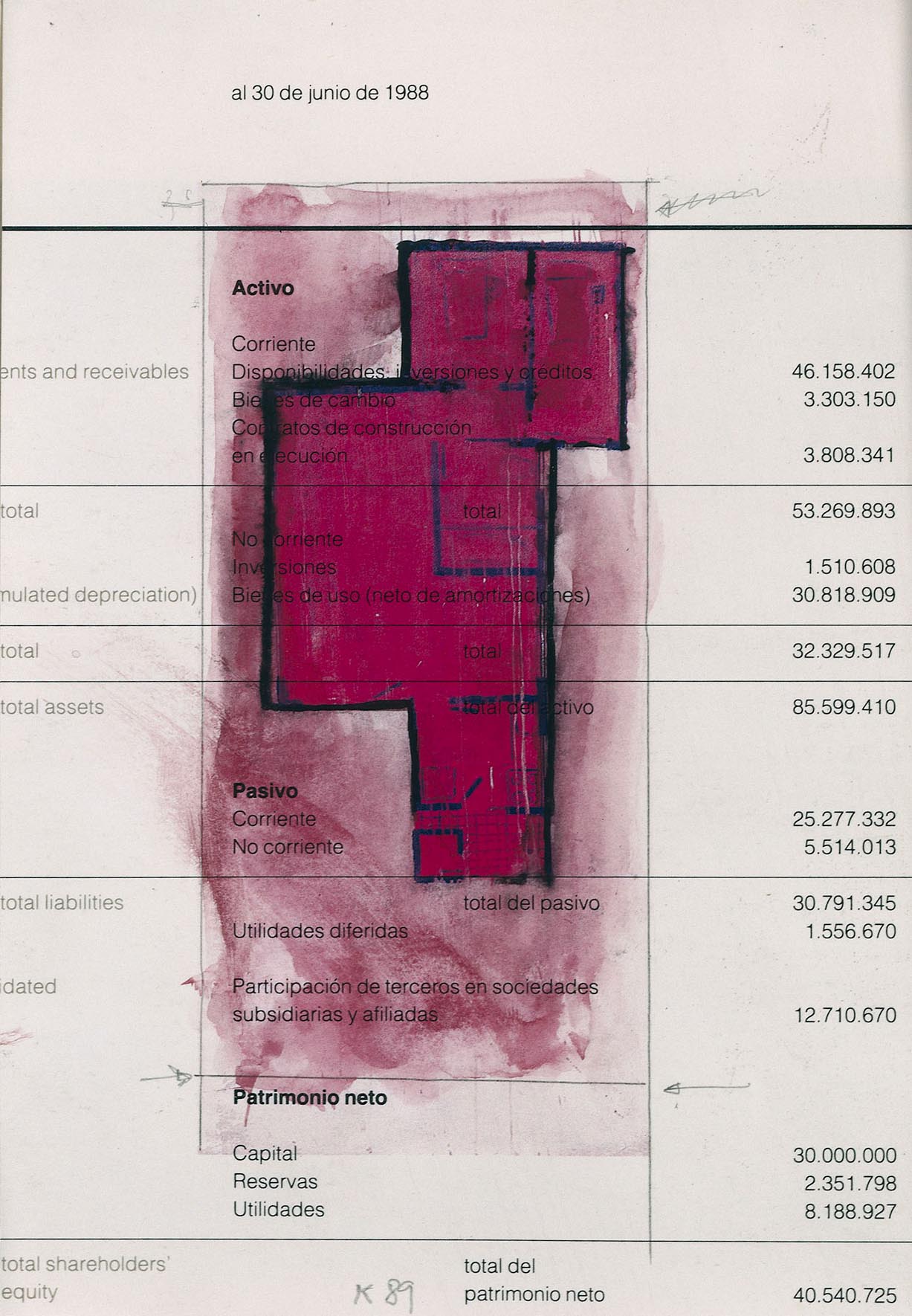

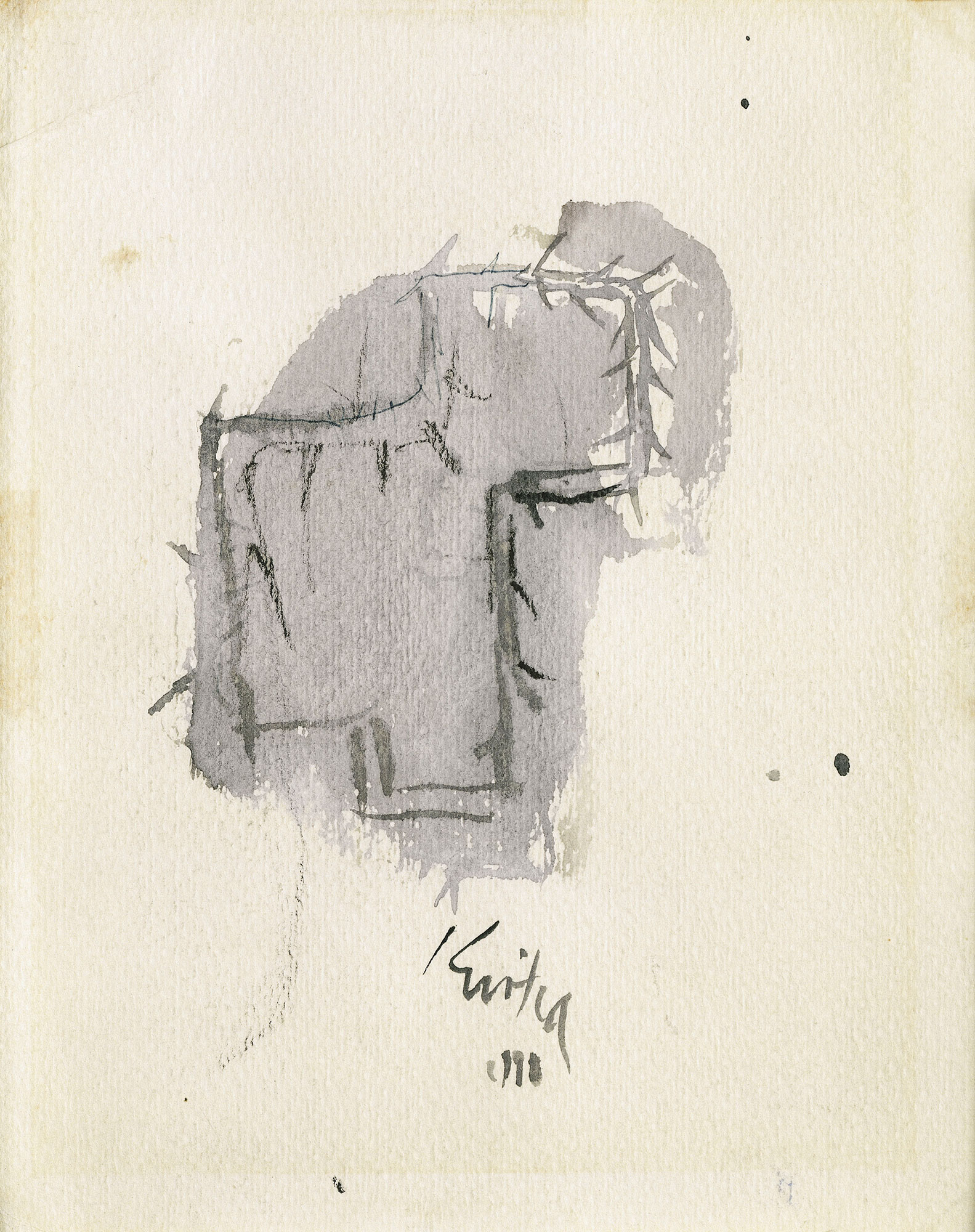

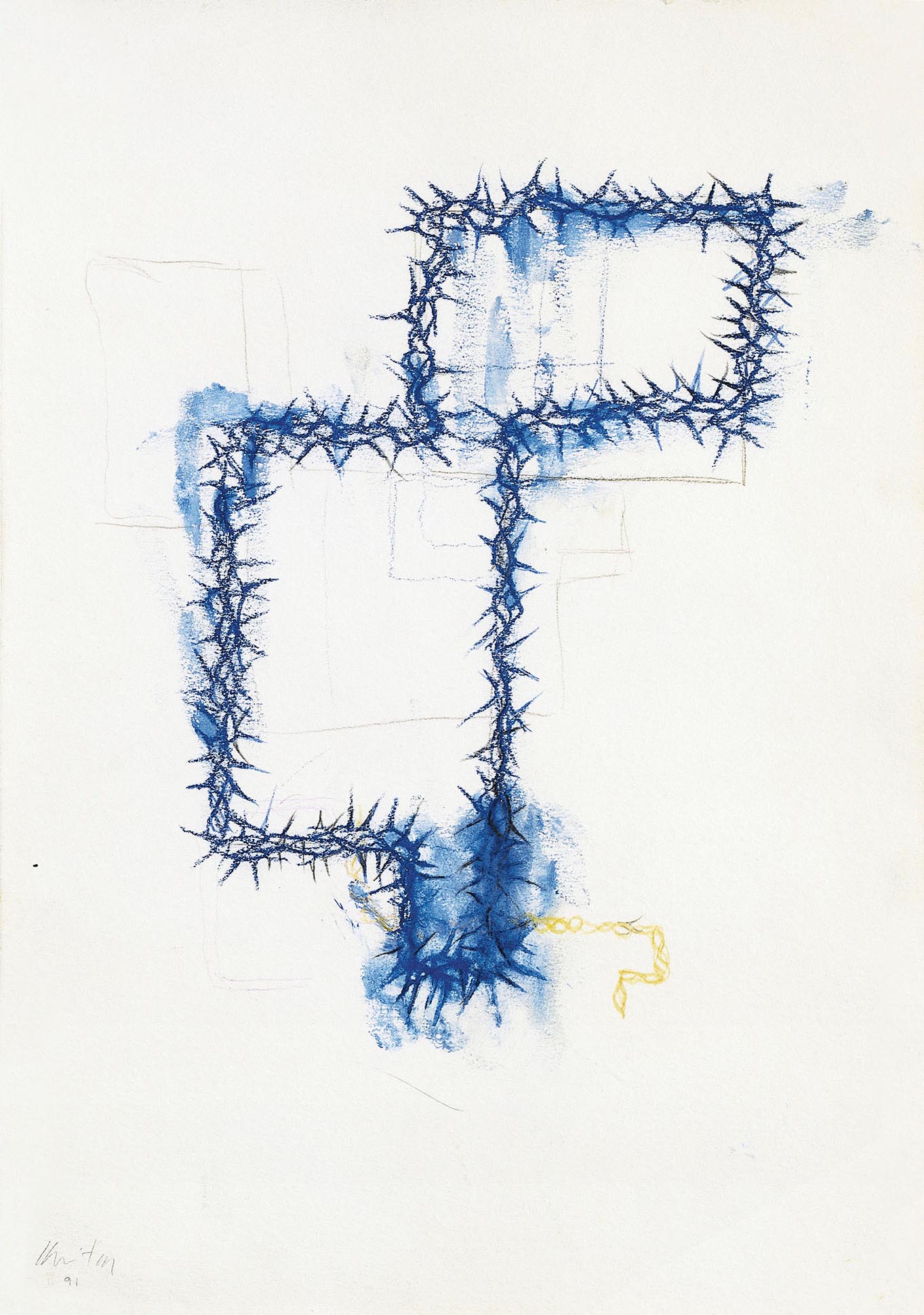

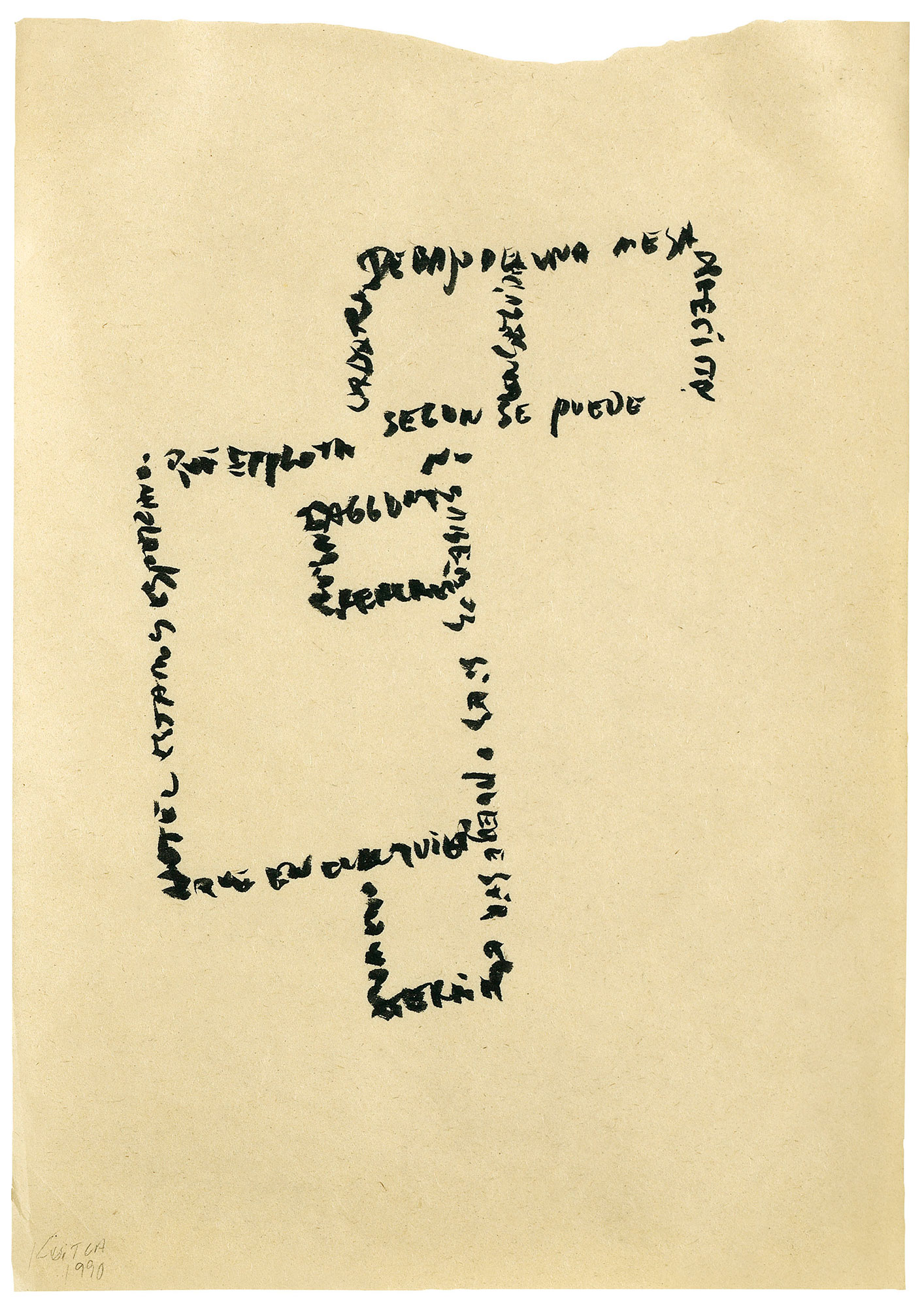

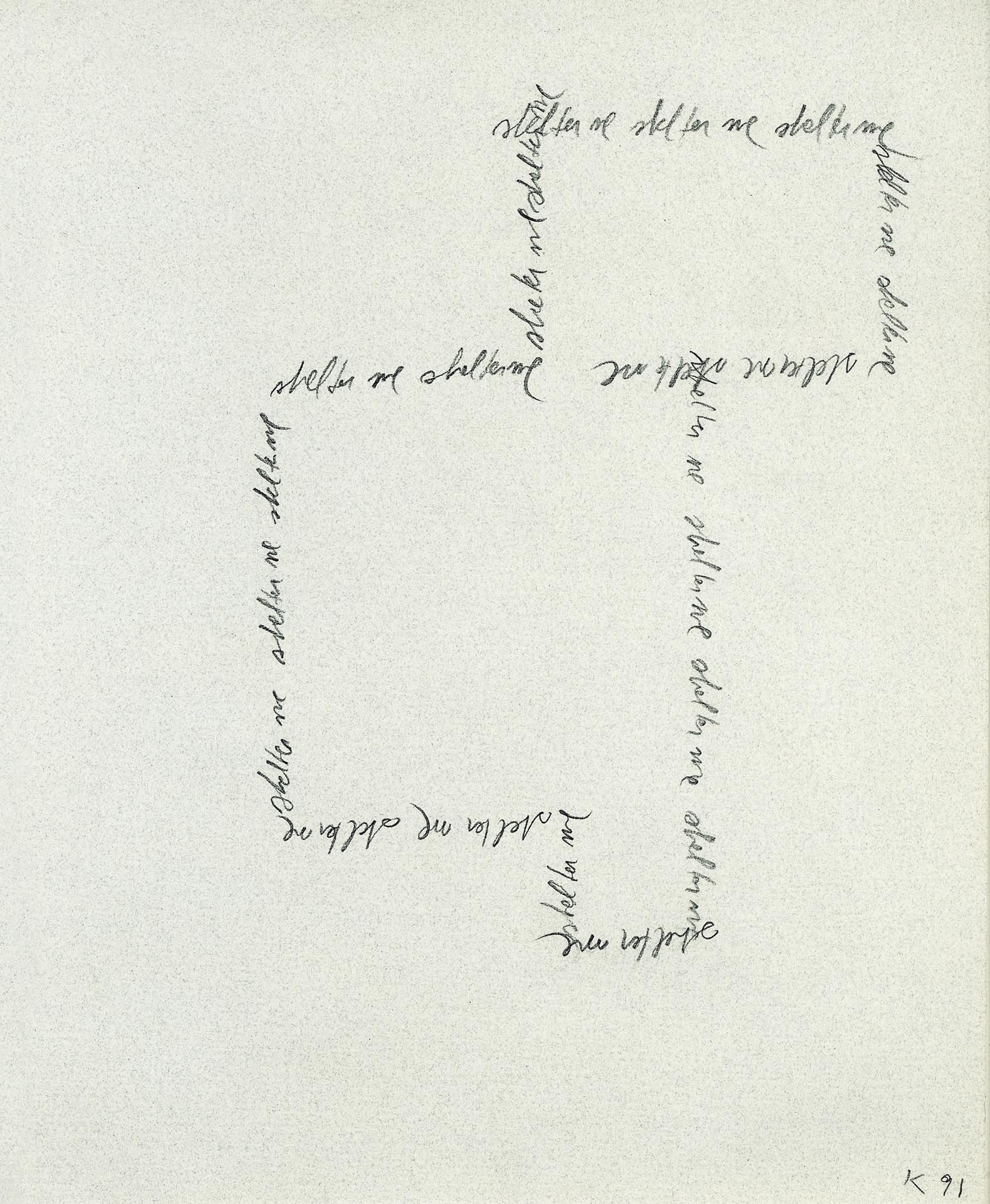

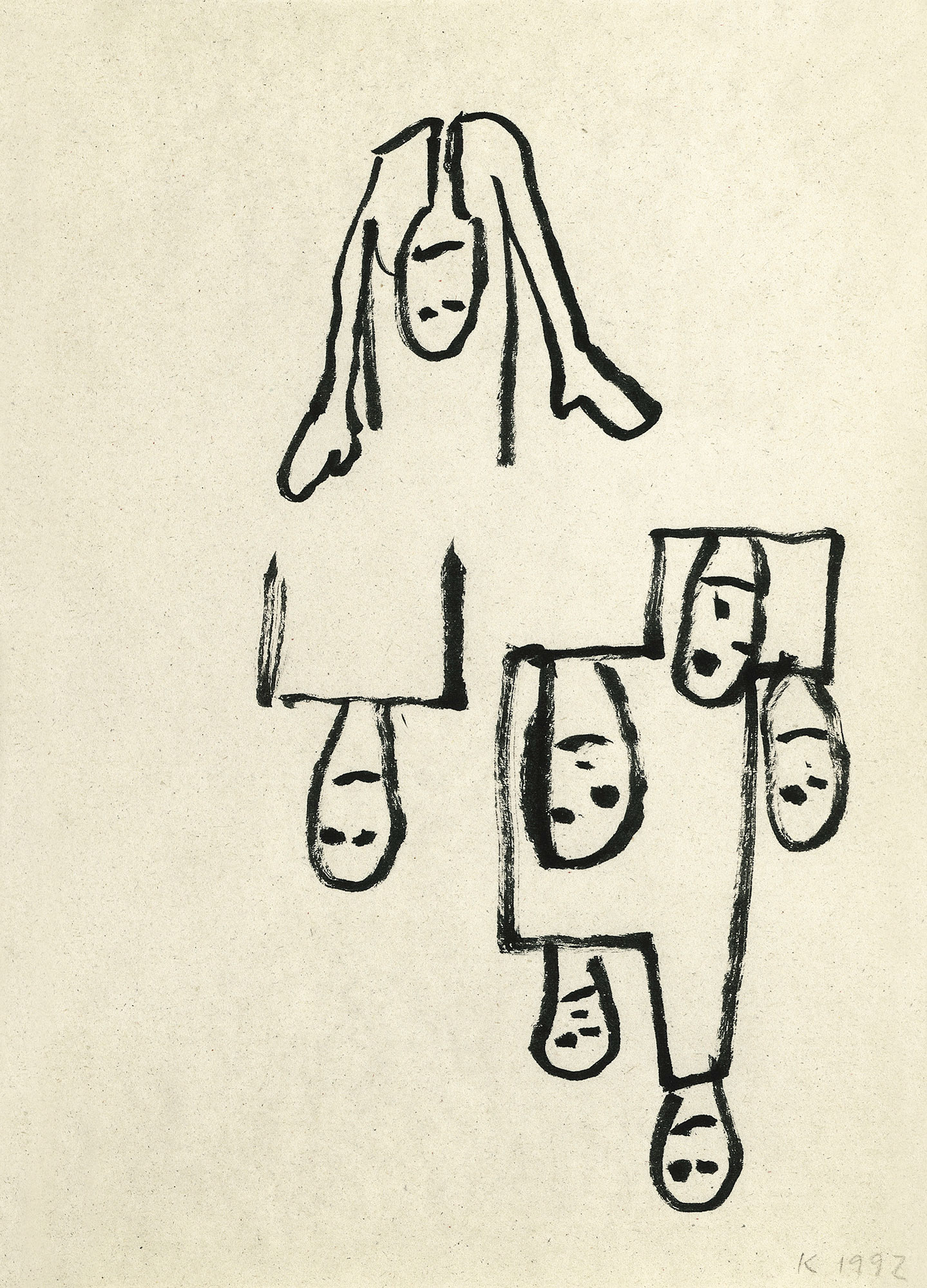

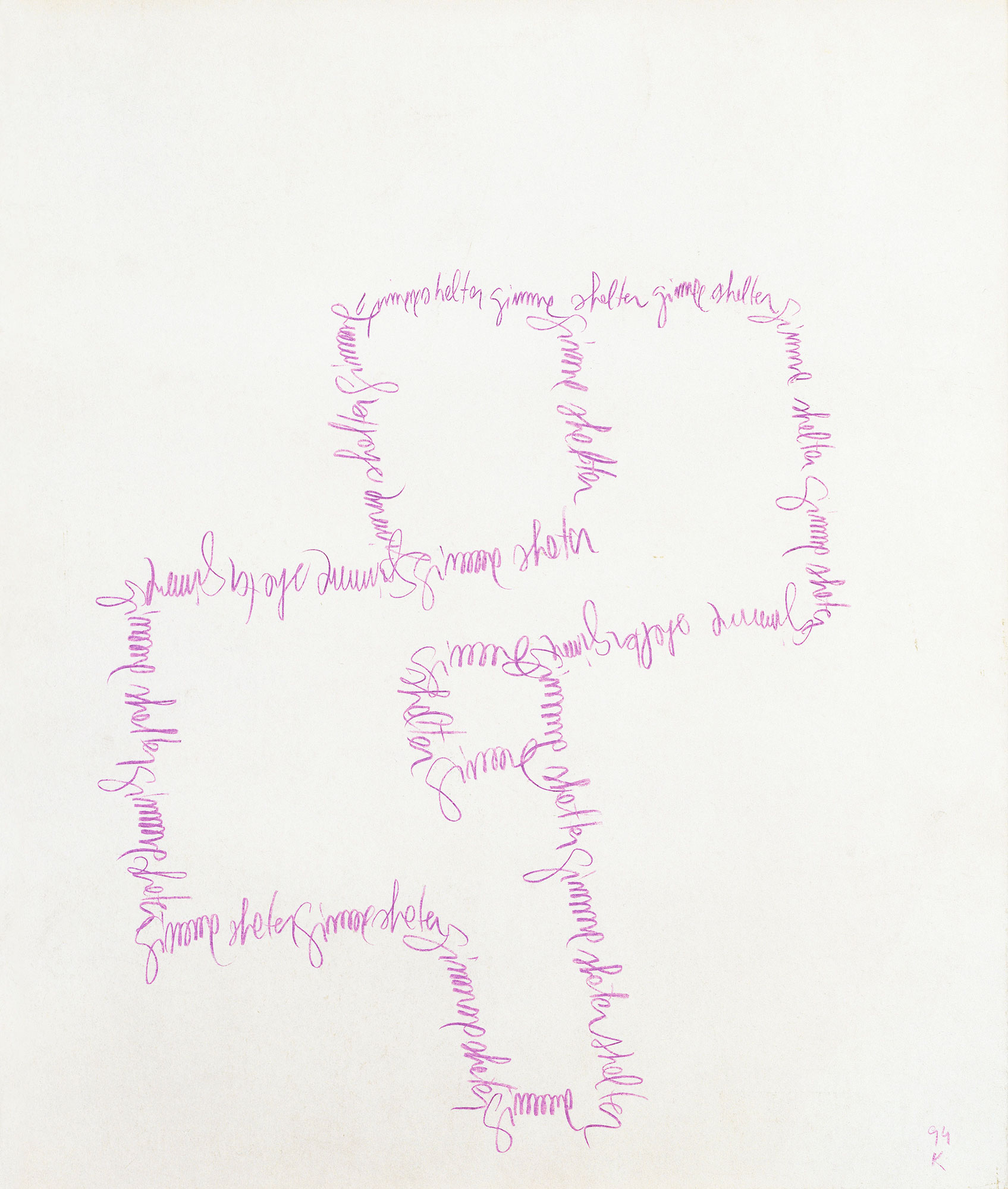

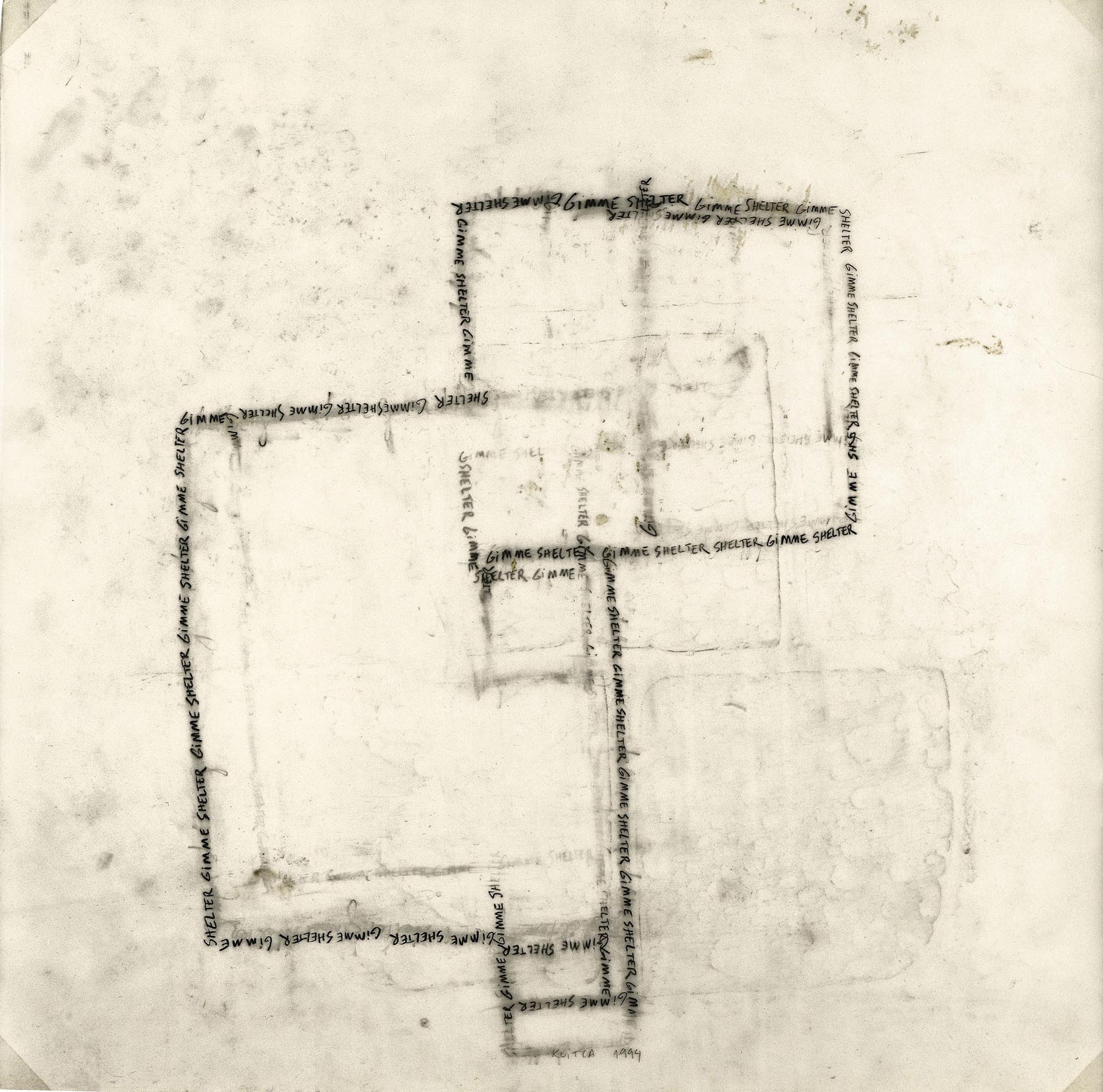

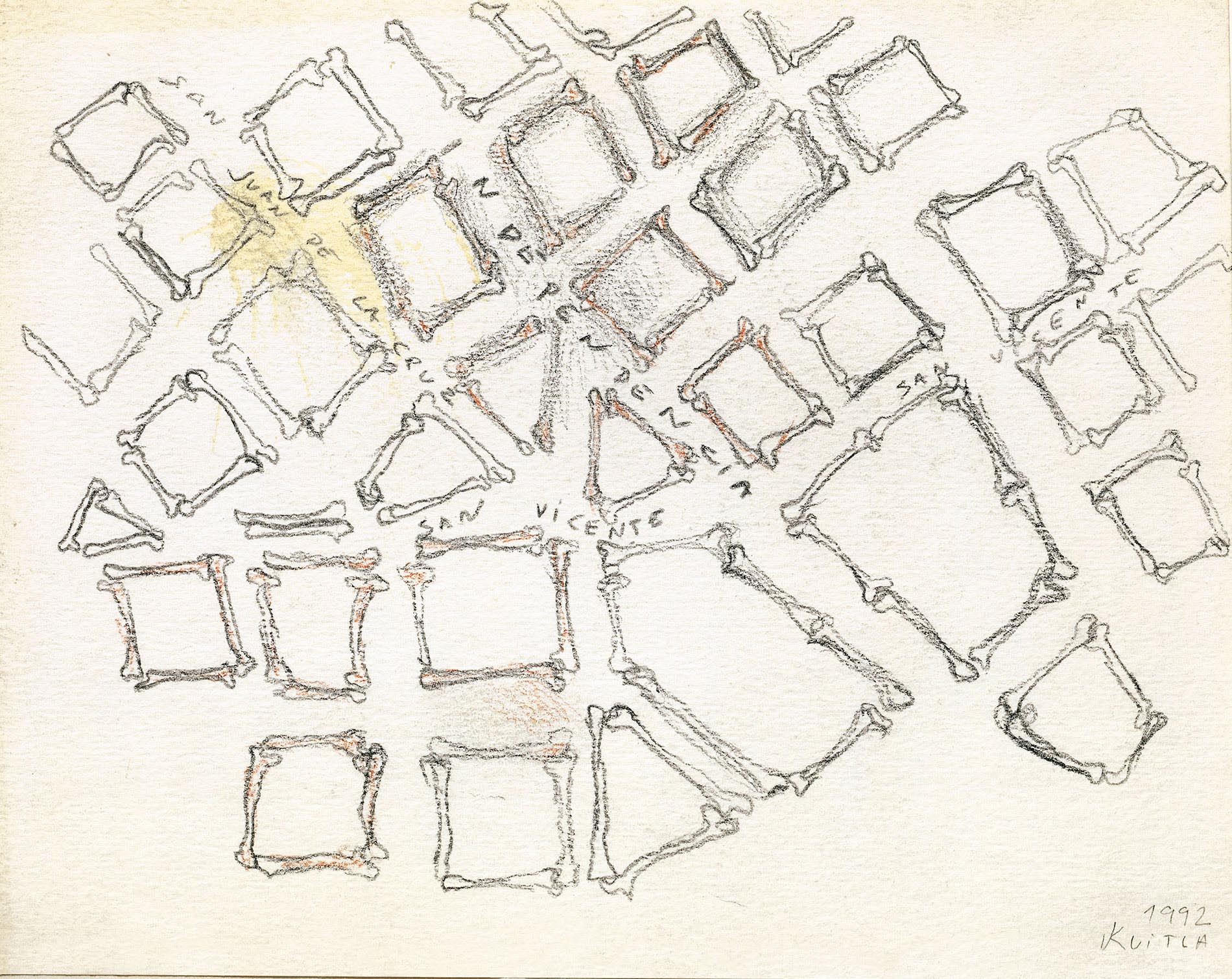

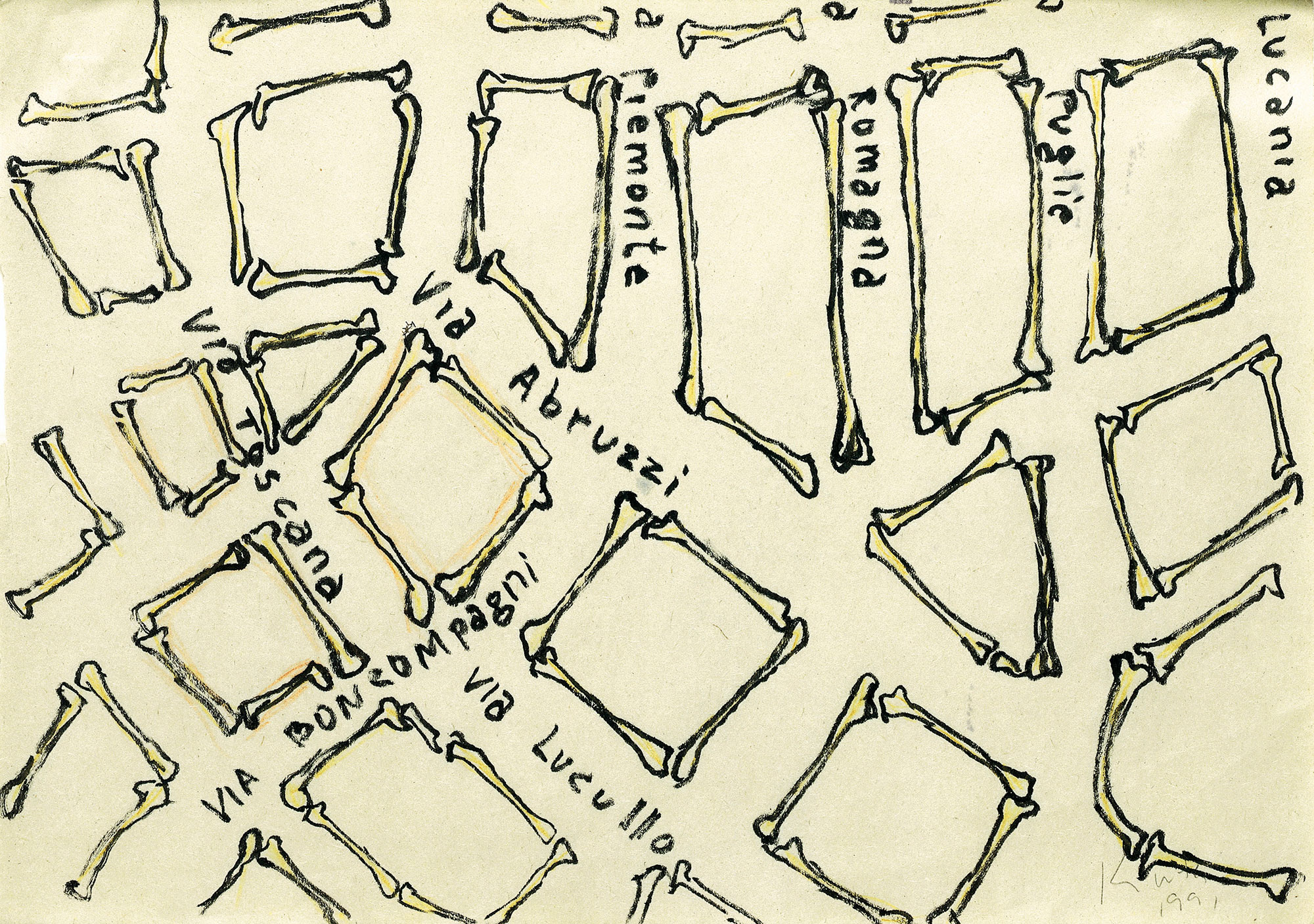

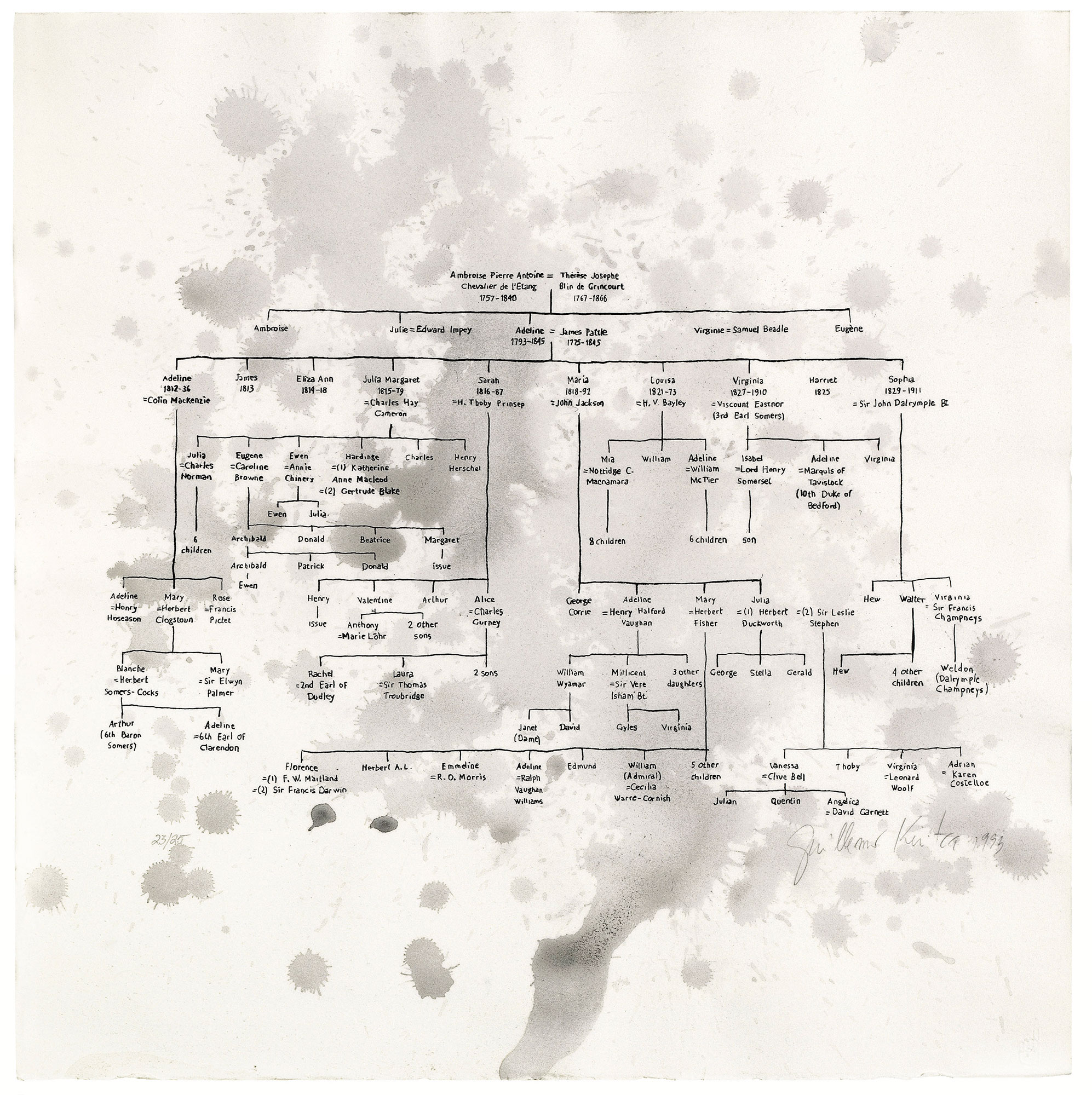

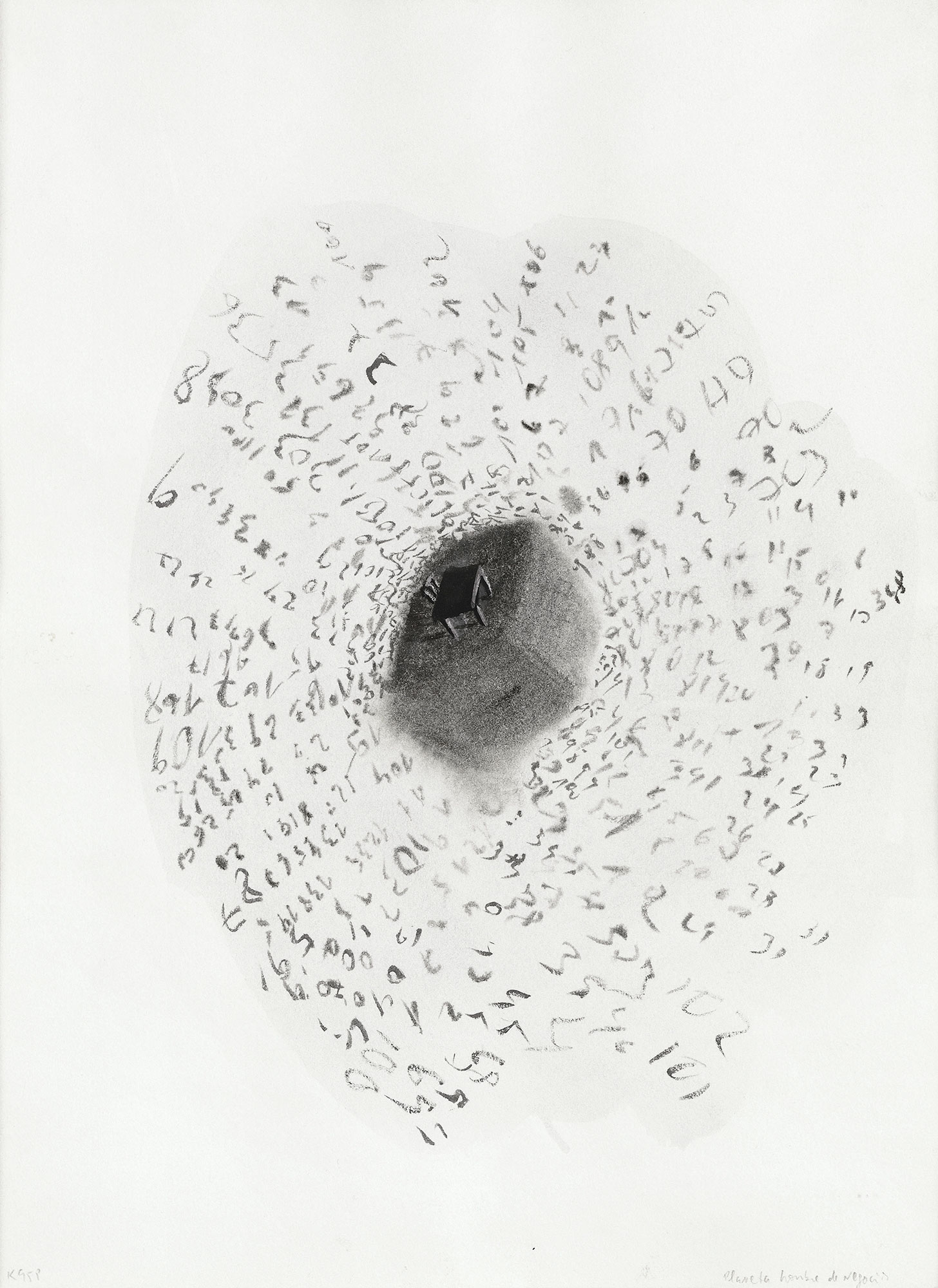

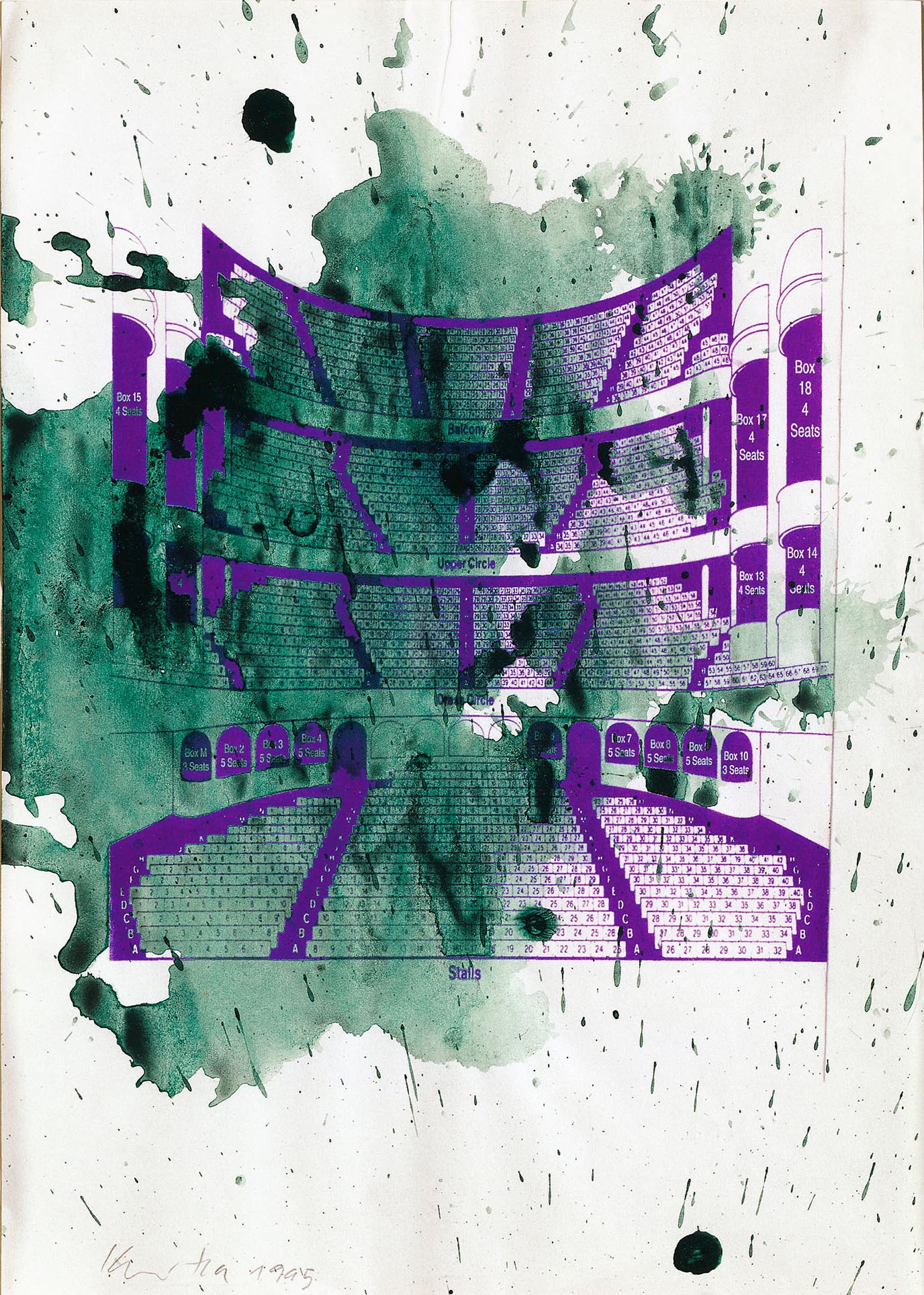

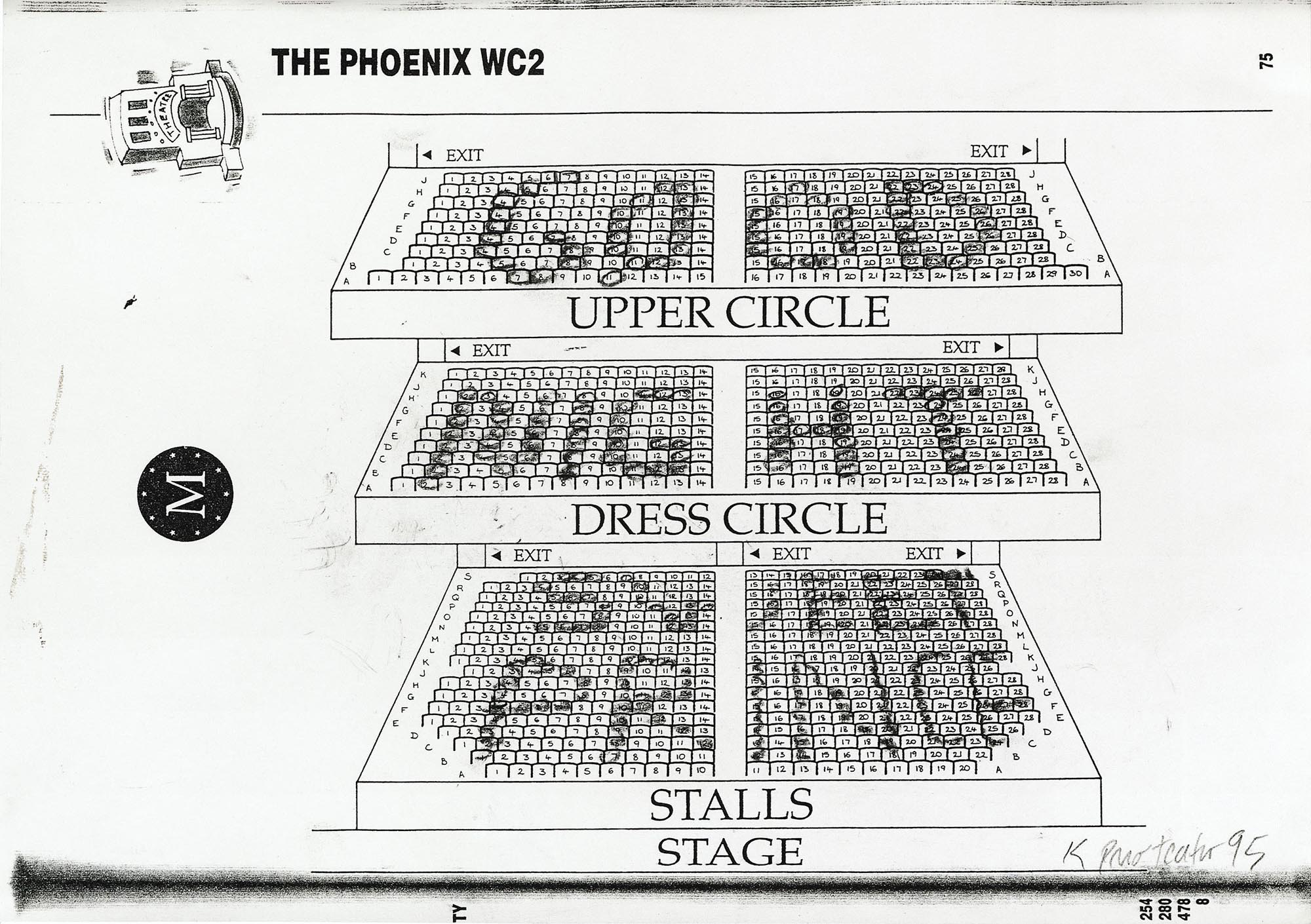

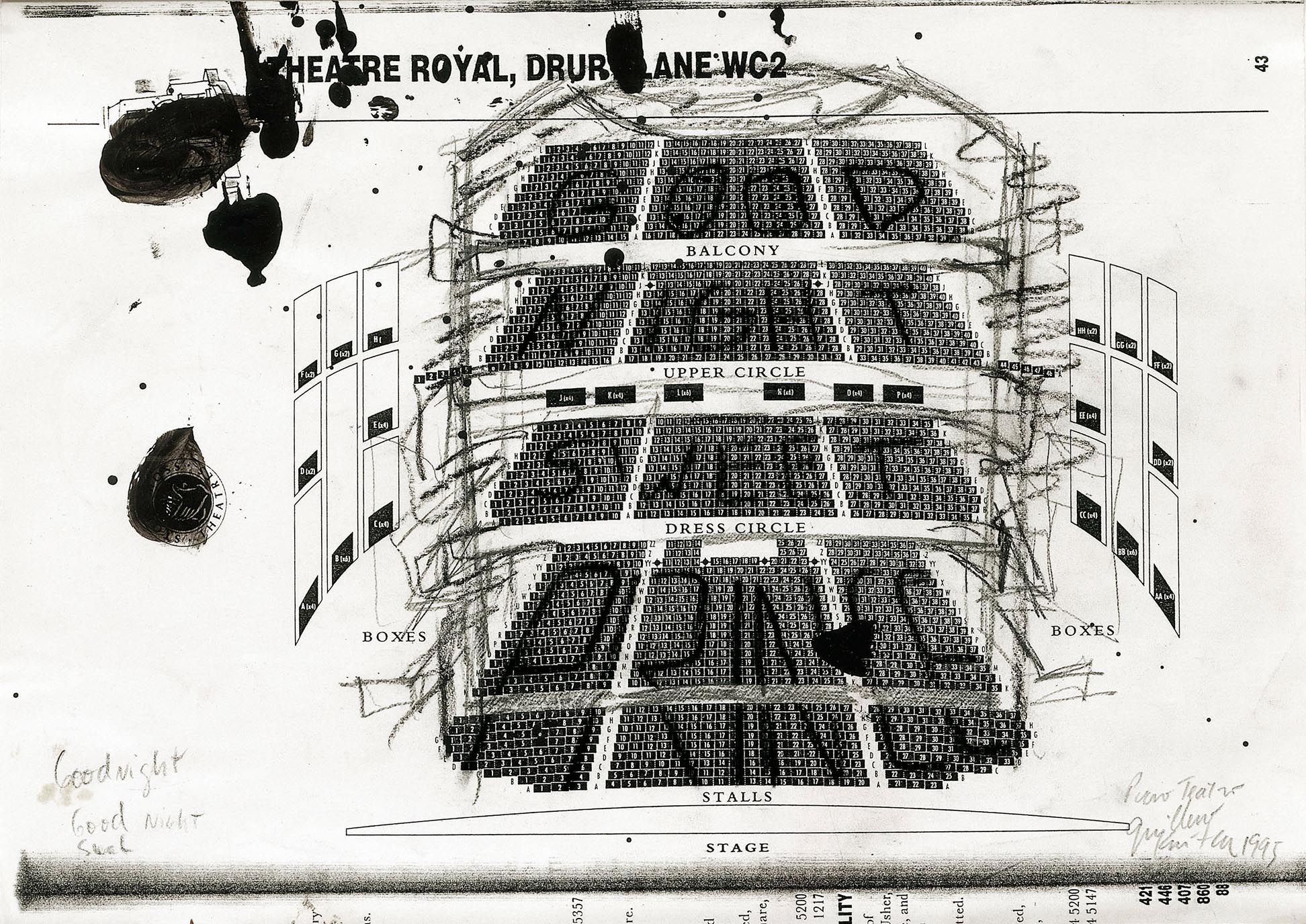

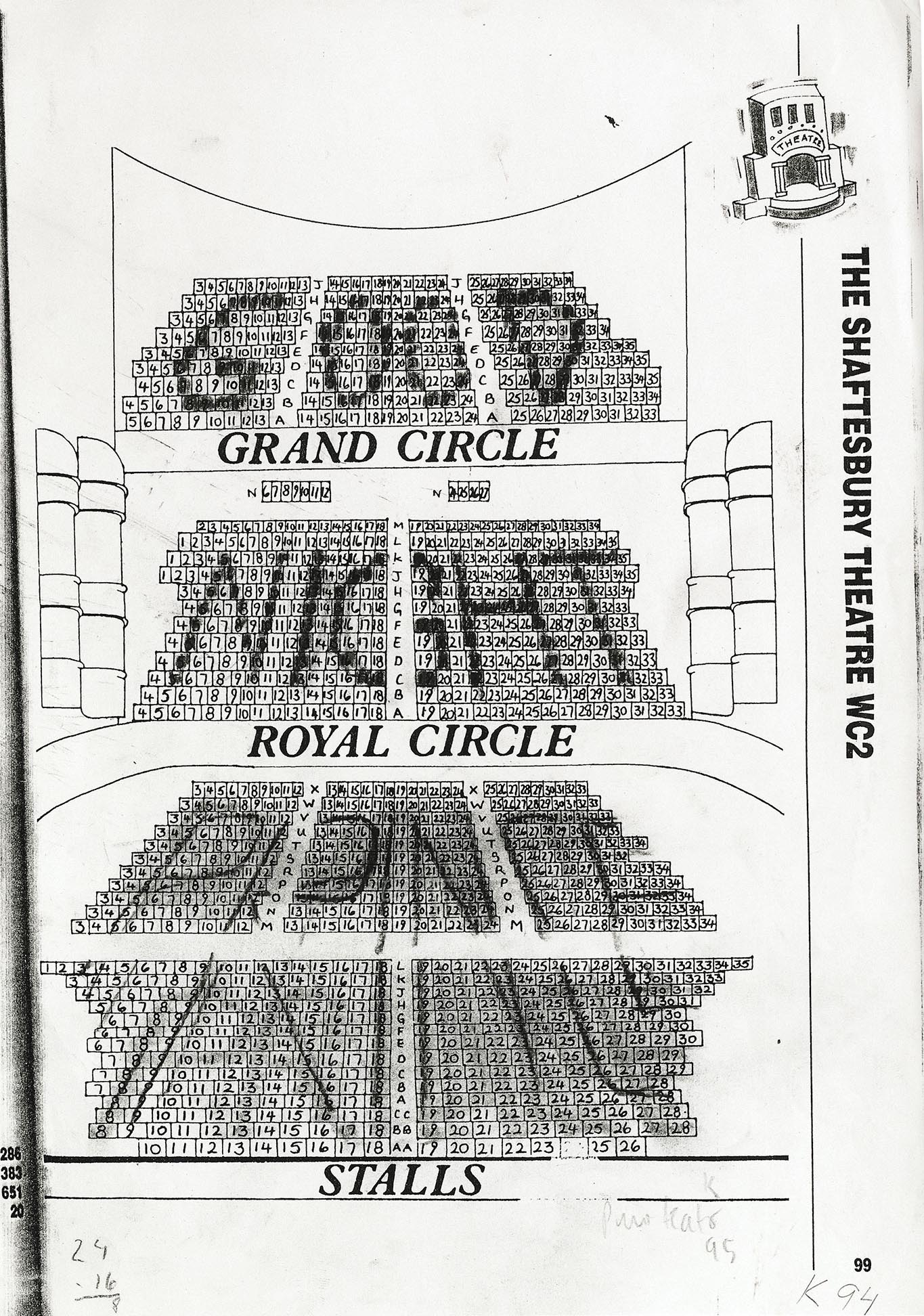

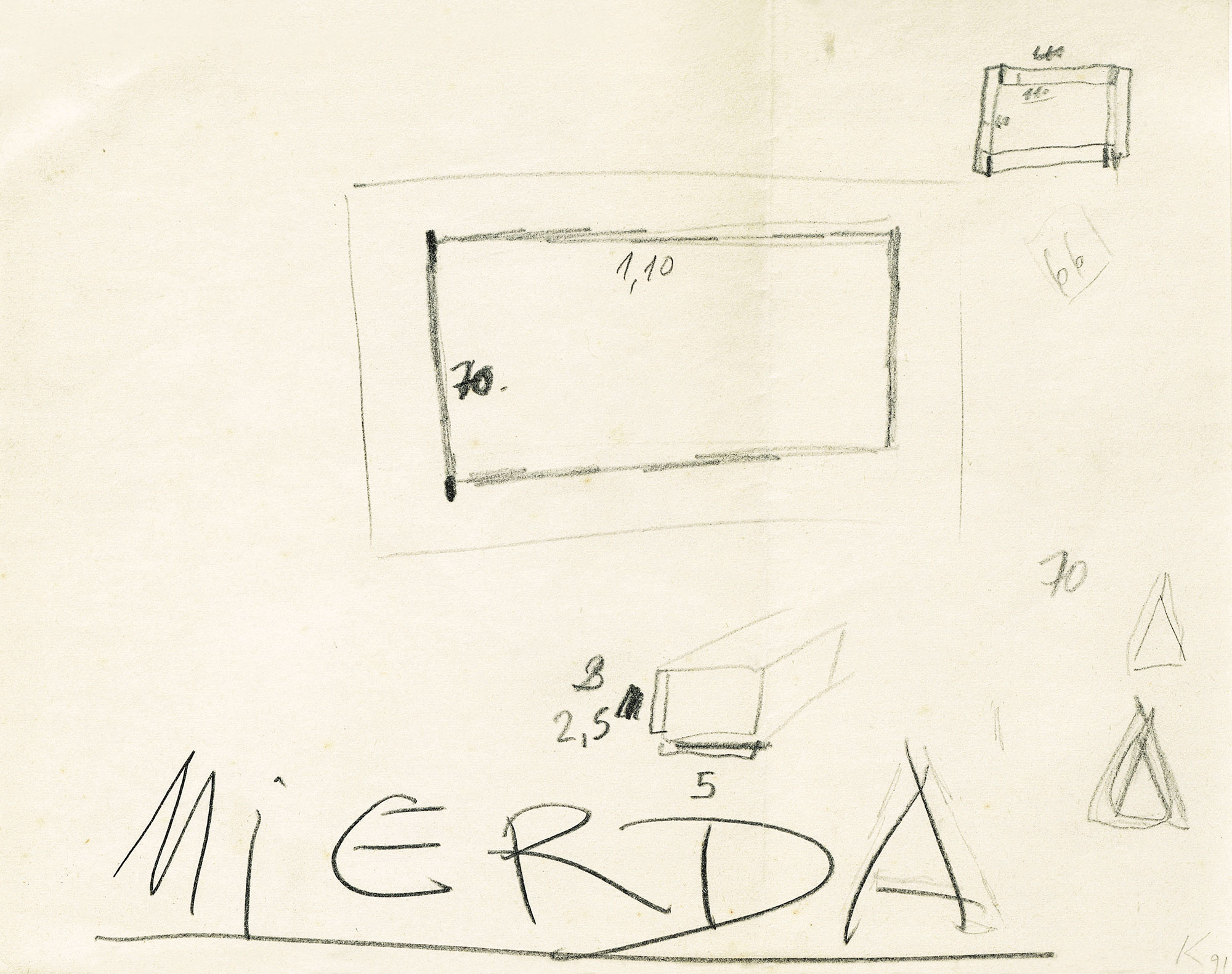

However, the interest in the expression of psychological drama that the artist demonstrated at the start of his career never let go of him. In the theatrical sets from the 1980s, all order was dismantled, with bodies clinging to objects and throwing themselves into insane behavior. In the apartment floor plans, Kuitca used the typical middle class home in Argentina to examine through a montage of different images the shifts in the sinister sides of private life. The floor plans were delineated with written sentences, crowns of thorns, or surrounded by fecal depictions, among other images. In the same way, city maps and theater floor plans lost their former neutrality and were transformed by way of the artist's sensitivity and the presence of stains and irregularities into signs of the mute violence that infuses Kuitca’s entire body of work.

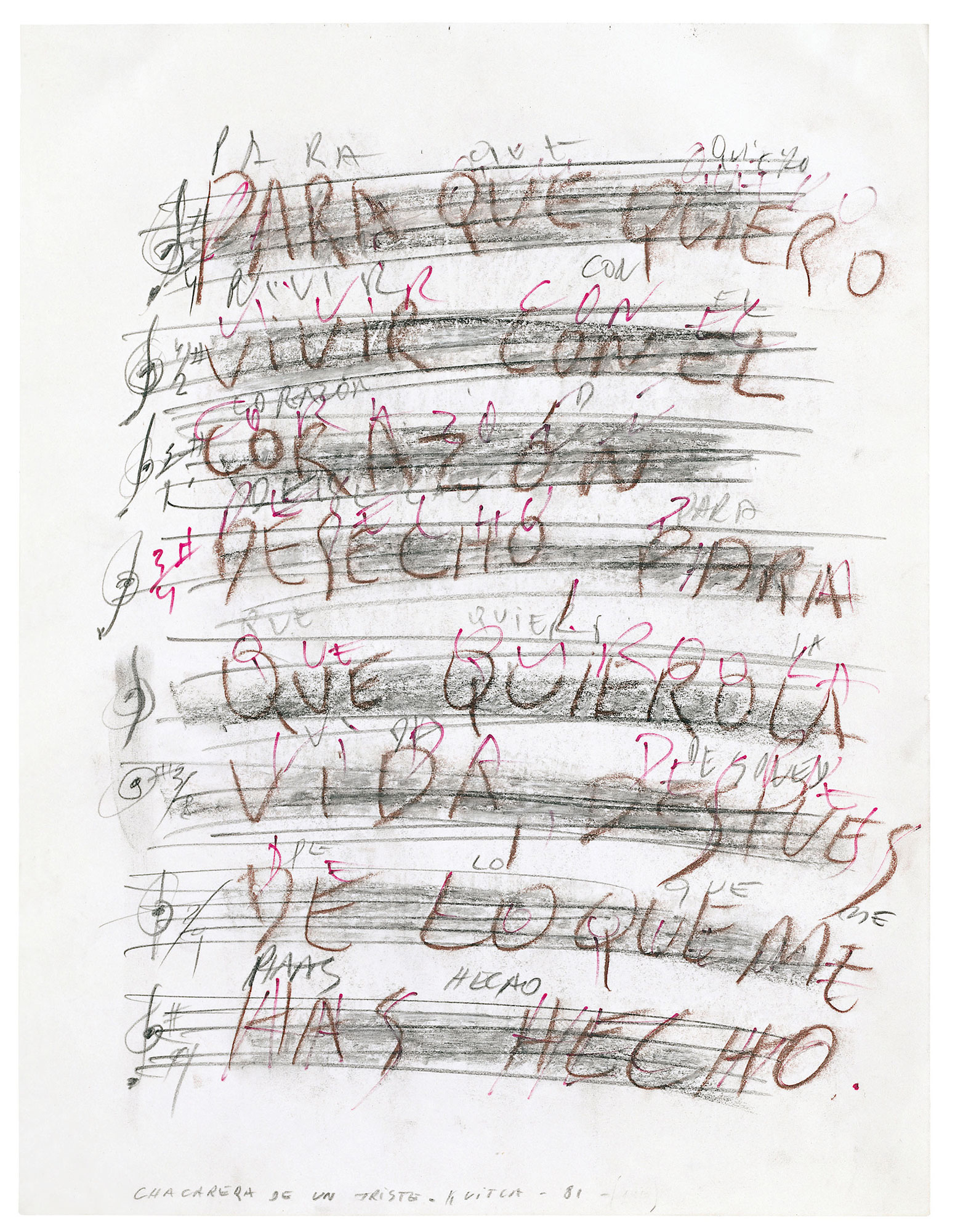

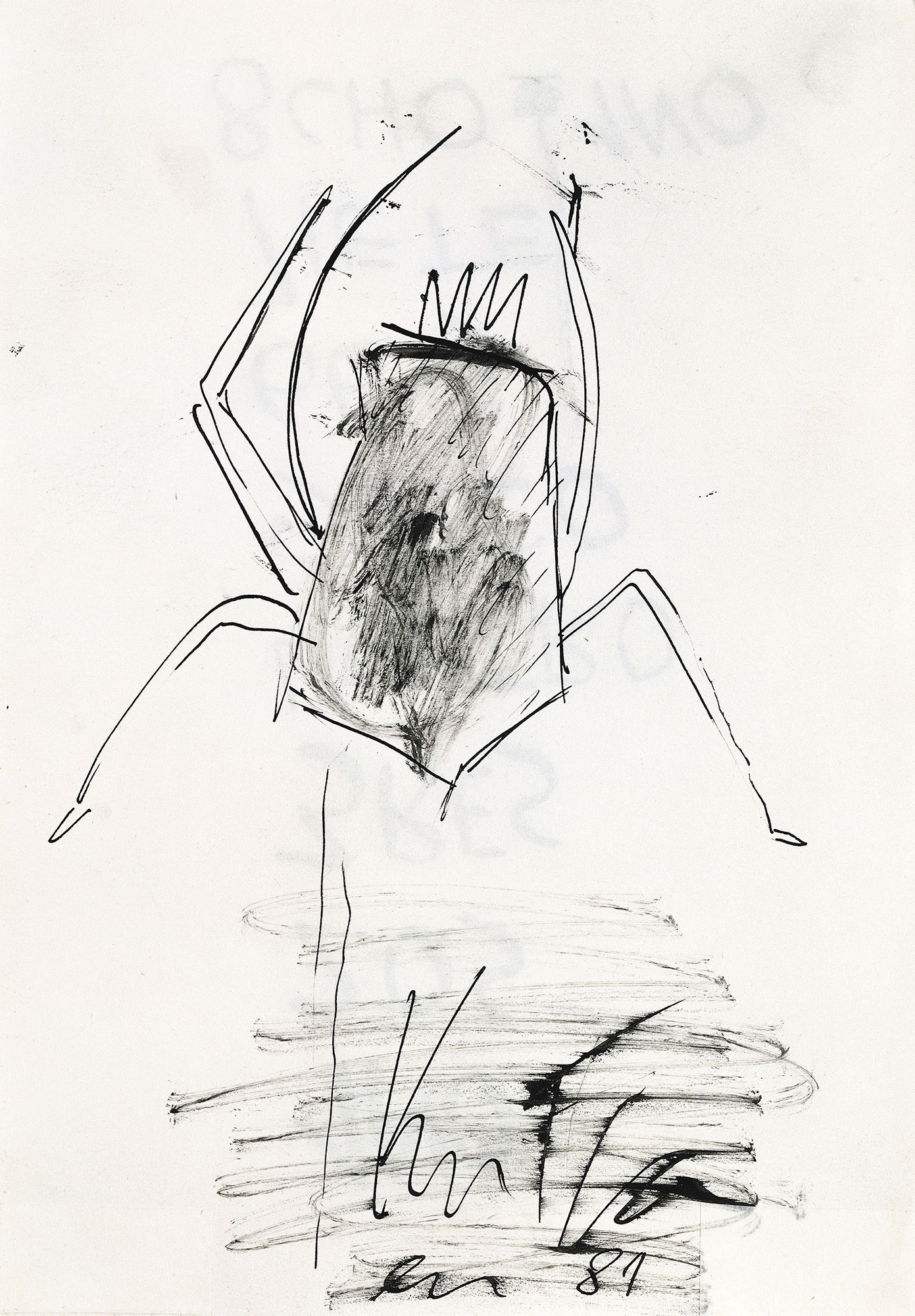

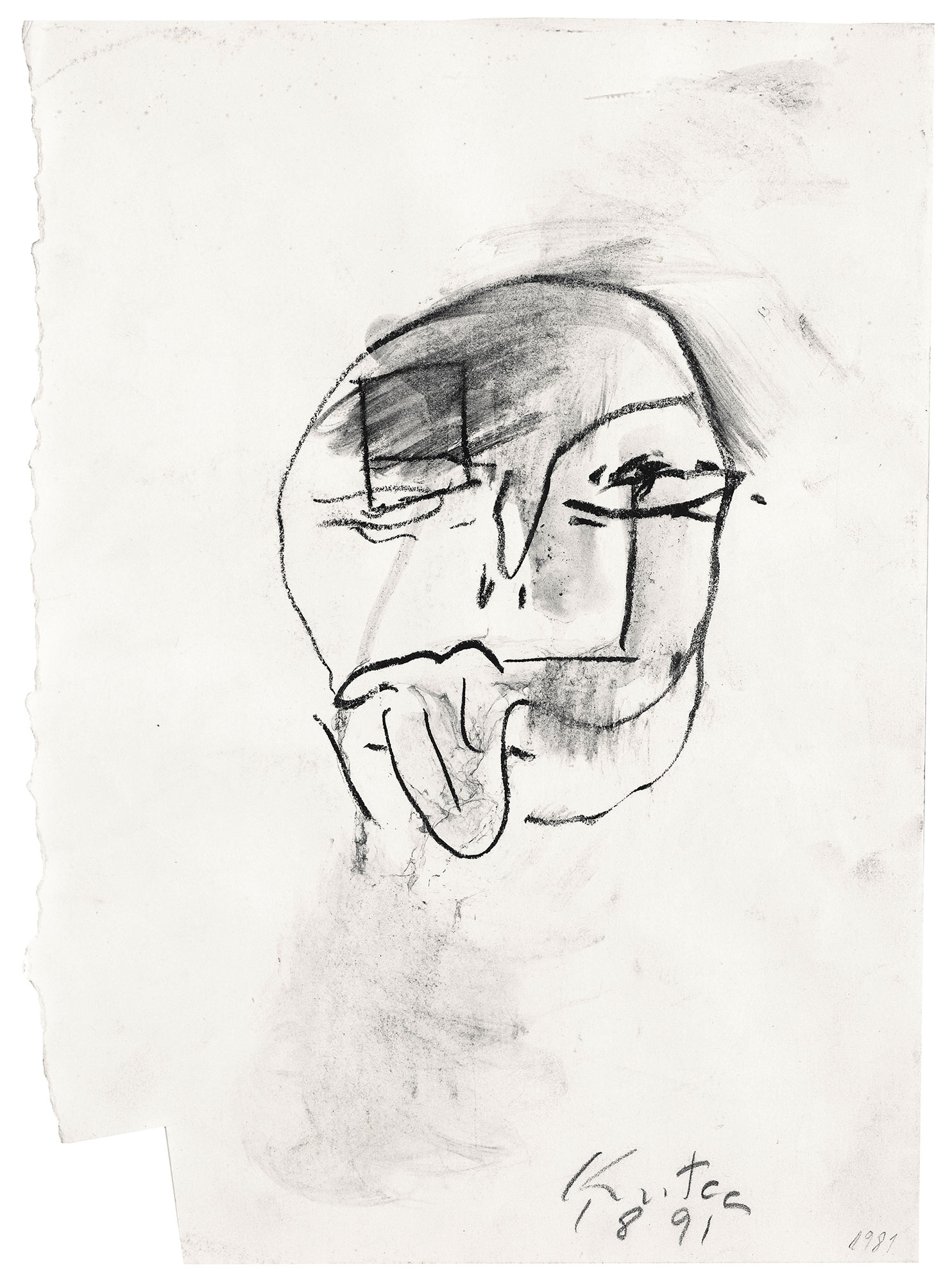

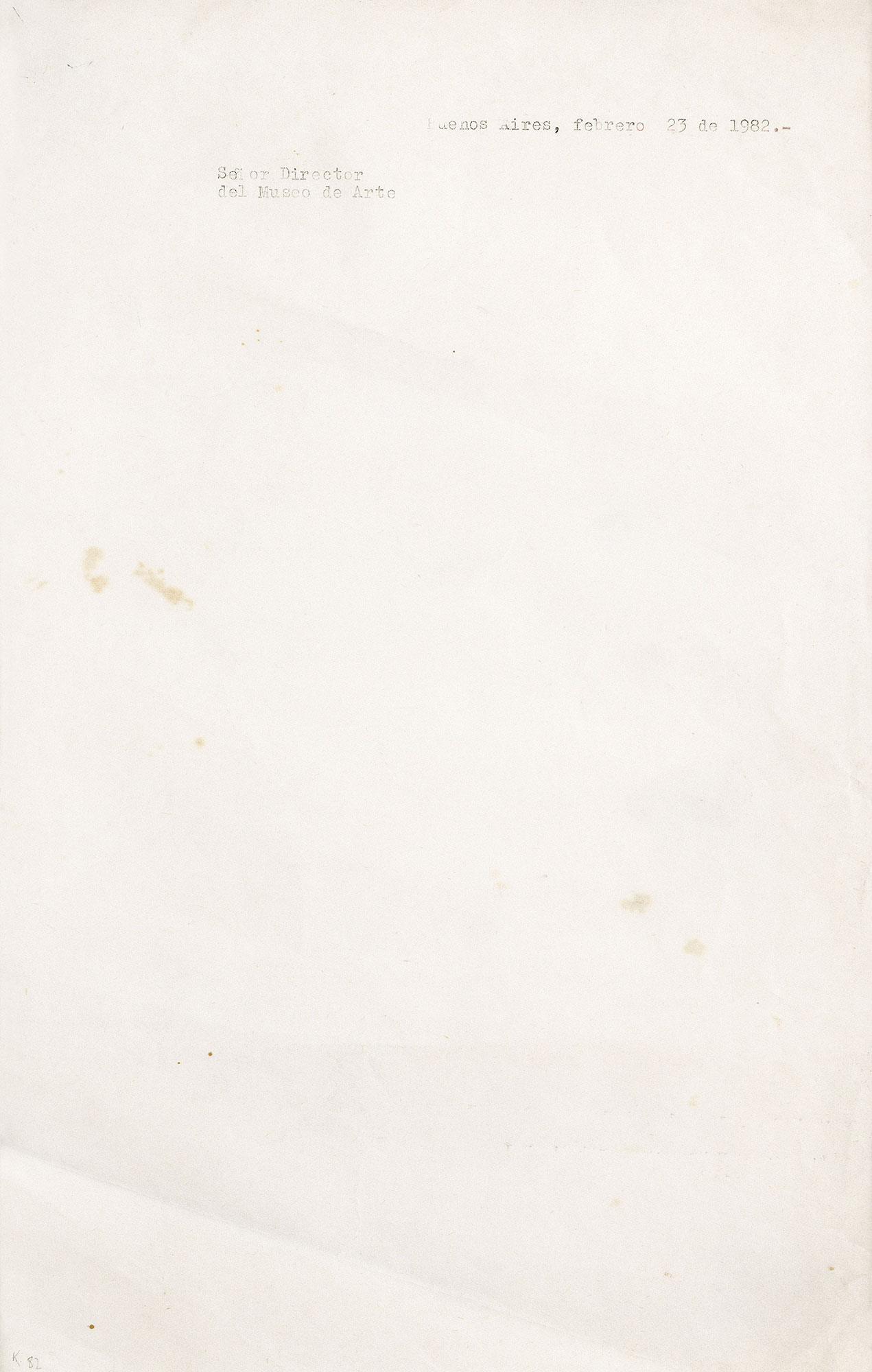

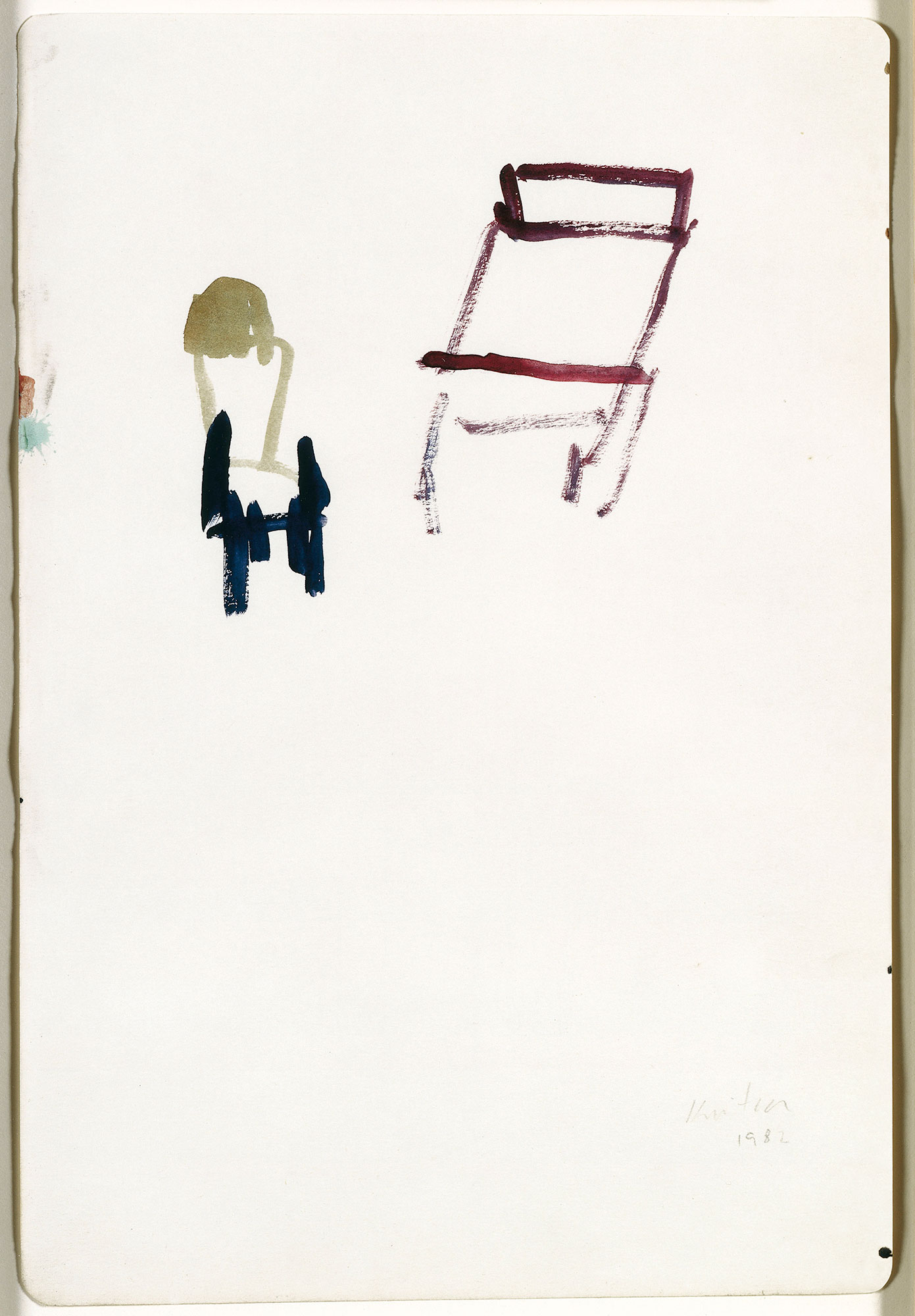

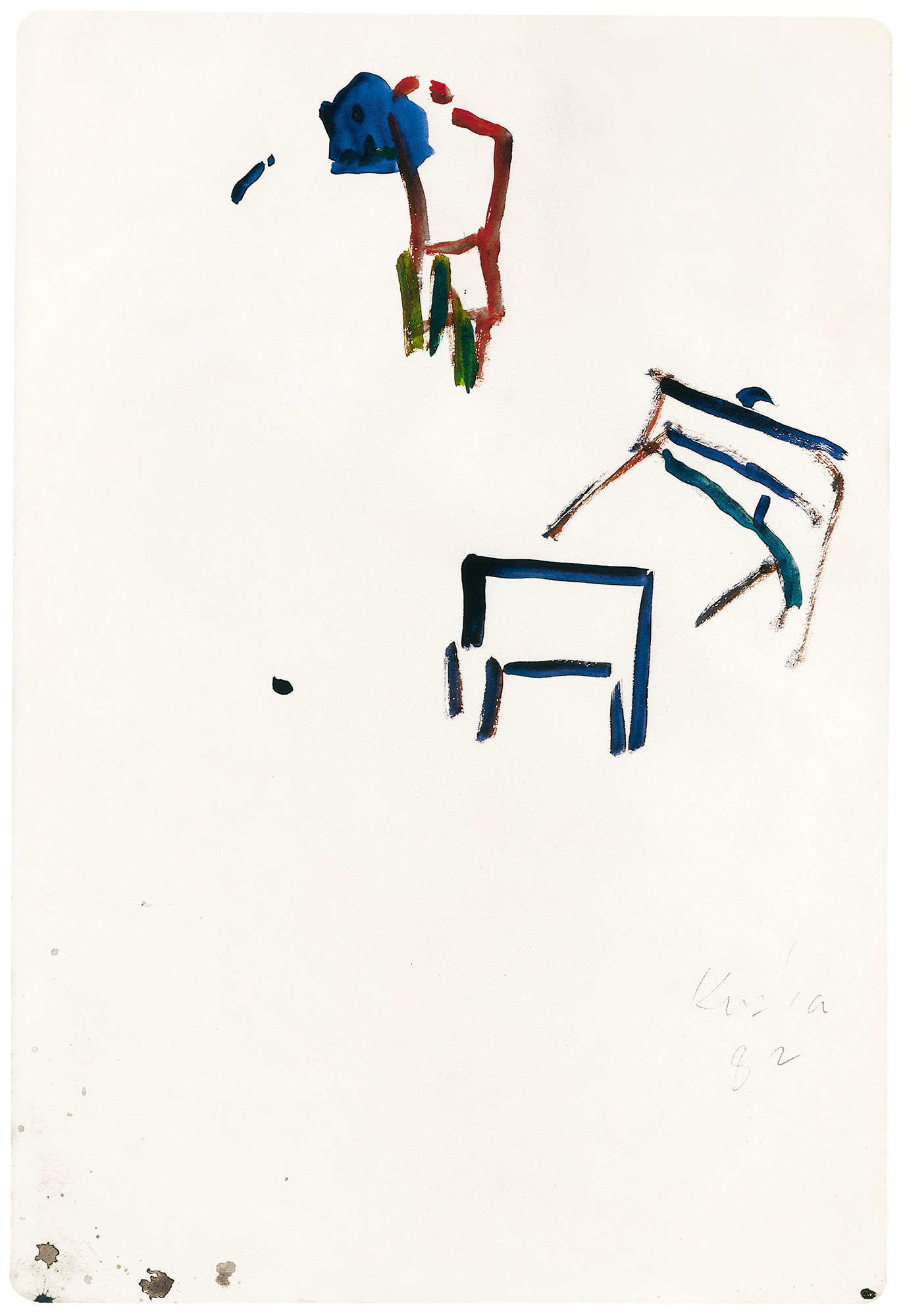

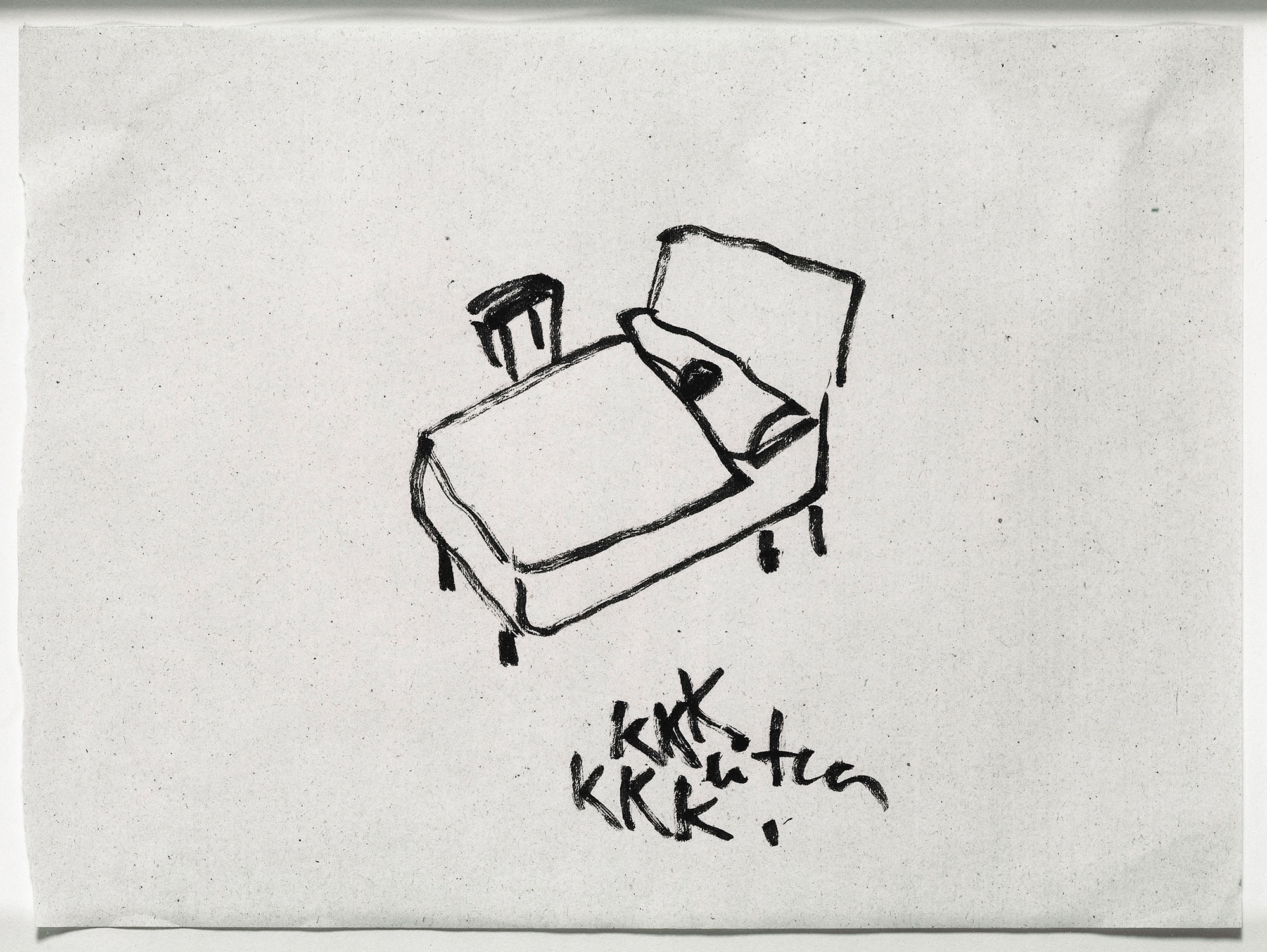

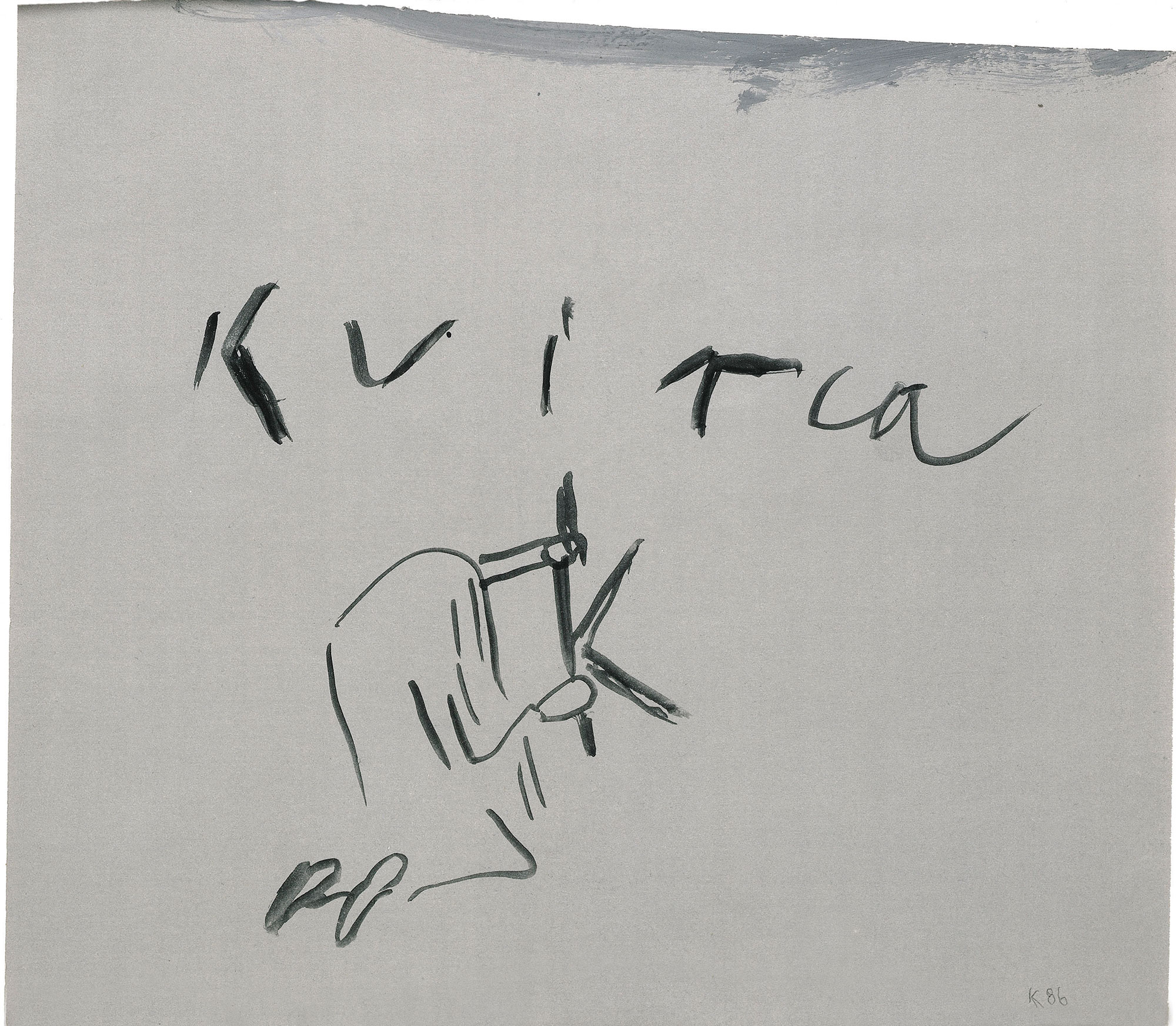

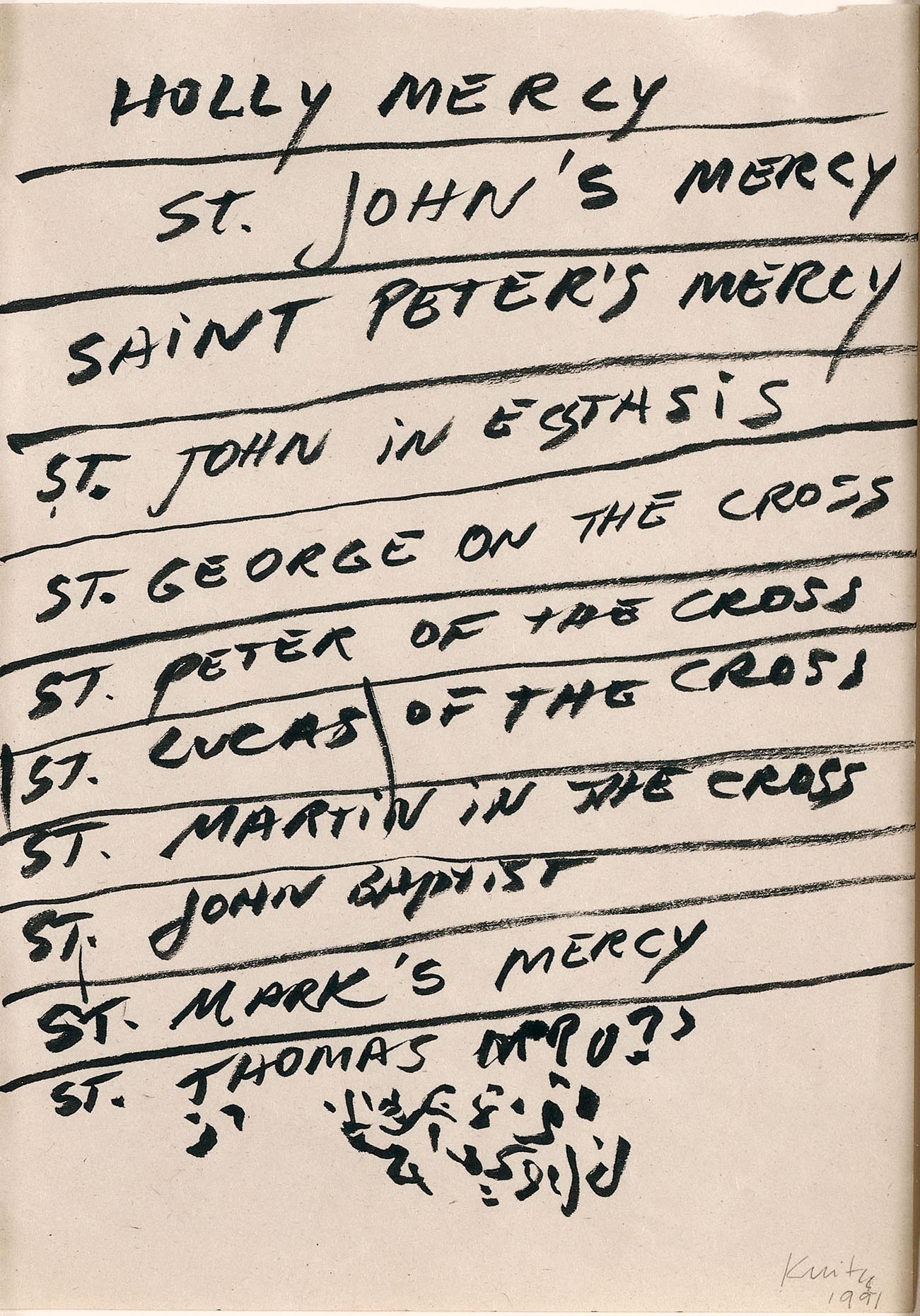

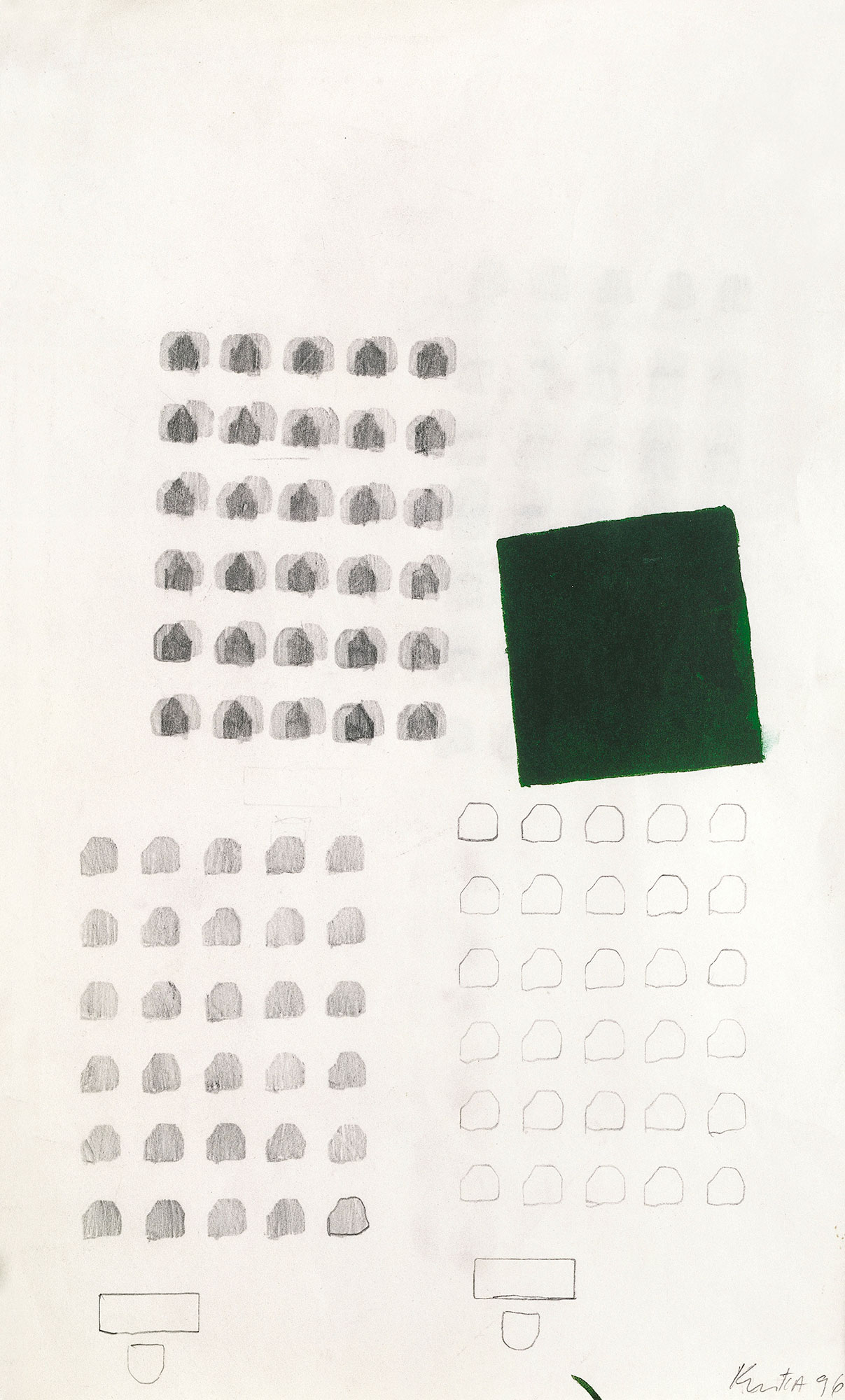

The 81 drawings in the Daros Latinamerica Collection are a perfect corpus for outlining drama as the constant and central theme of Kuitca’s work, achieved through the persistent representation of confinement, instability and imbalance—without, however, abandoning humor. Created between 1981 and 1996, the drawings display the fundamental issues of those years (figures, beds, signatures, maps, architectural plans, diagrams, theaters) and therefore constitute a revealing retrospective collection. Among the series are unsettling schematic drawings, such as those in the 1982 Nadie olvida nada (Nobody forgets anything); a convincing group of apartment floor plans developed between 1989 and 1994; a set of city maps, theaters and genealogical charts; as well as a number of individual works, such as the early, unfinished letter to a museum director in 1982, and a 1994 illustration for Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince.

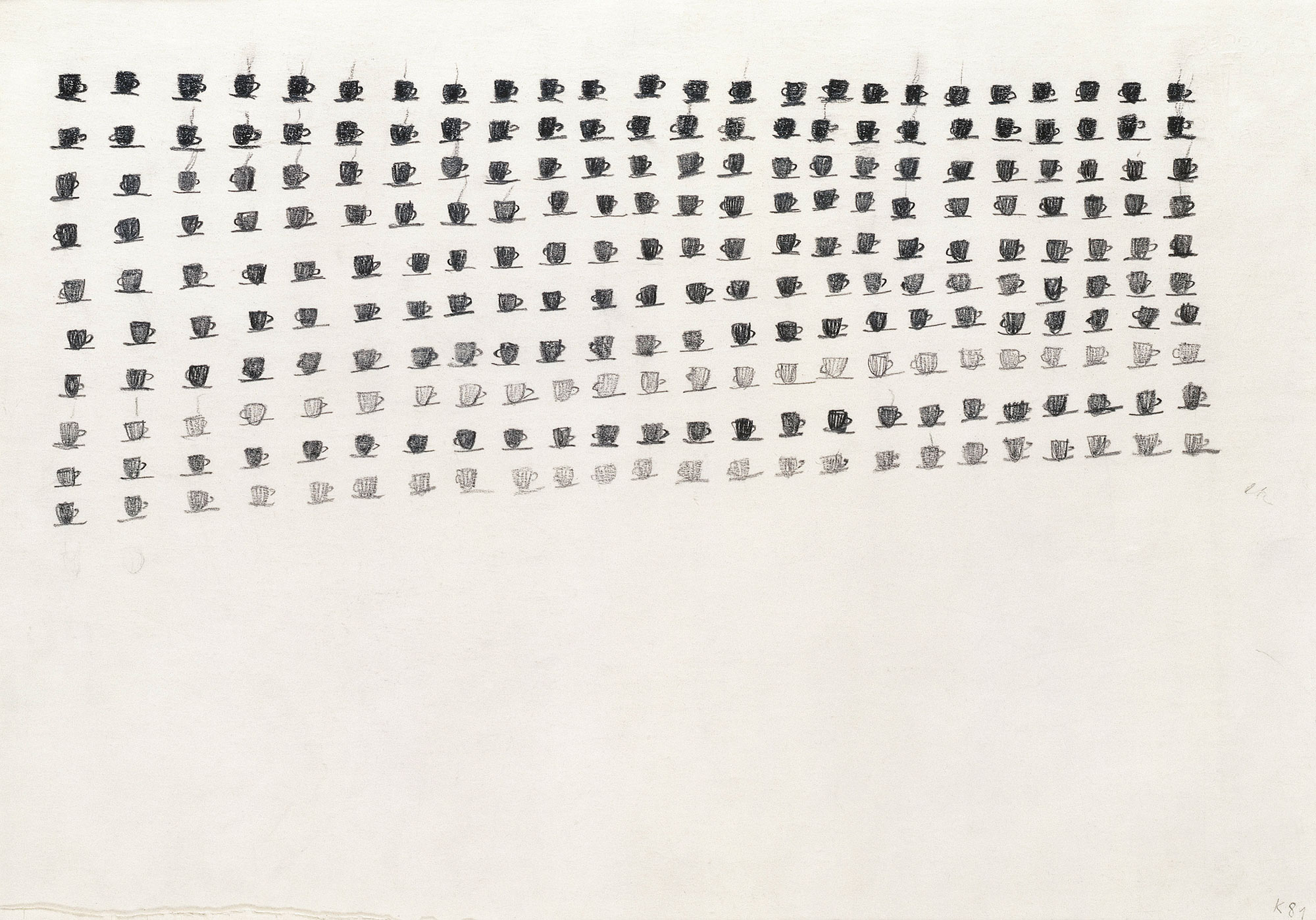

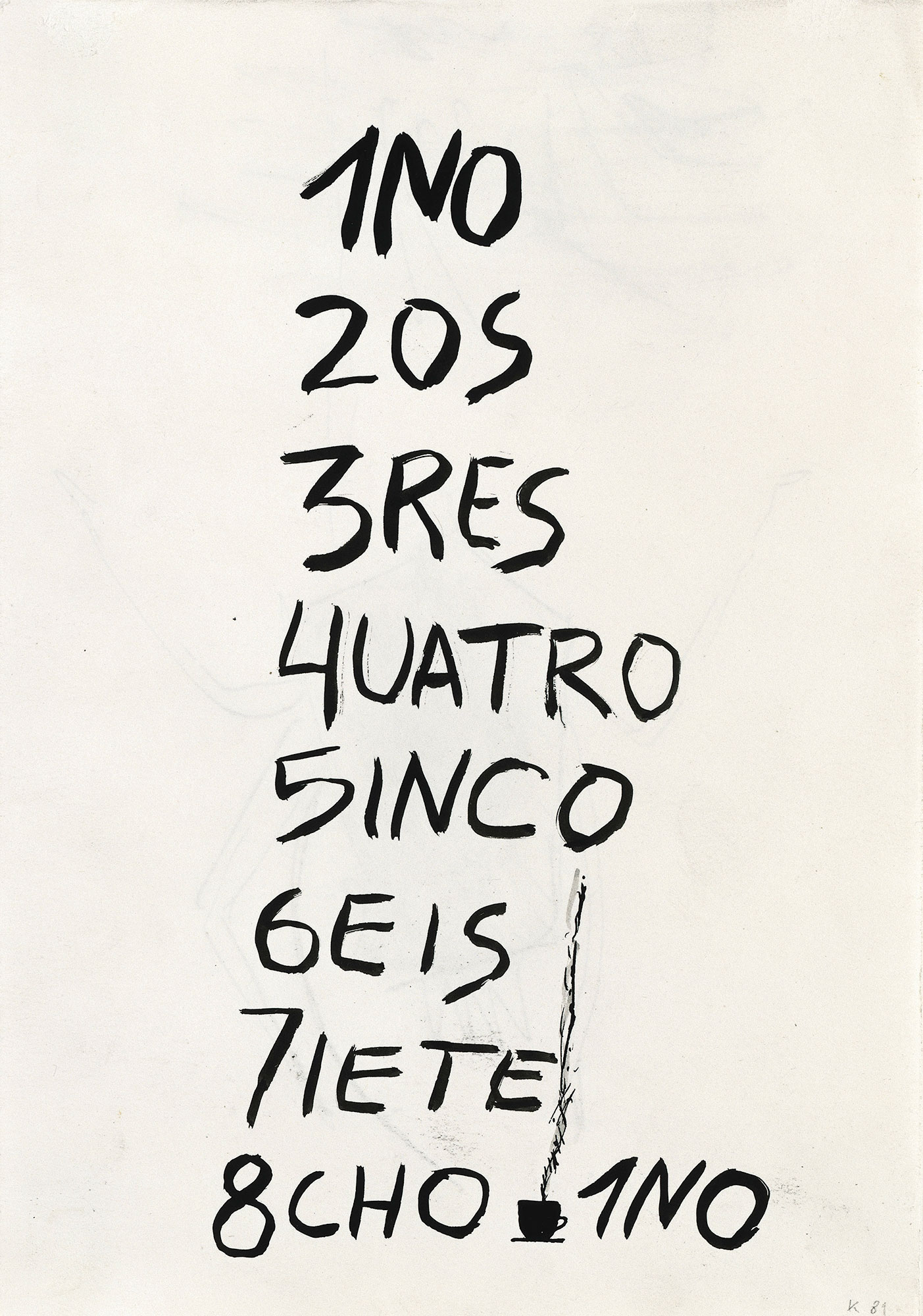

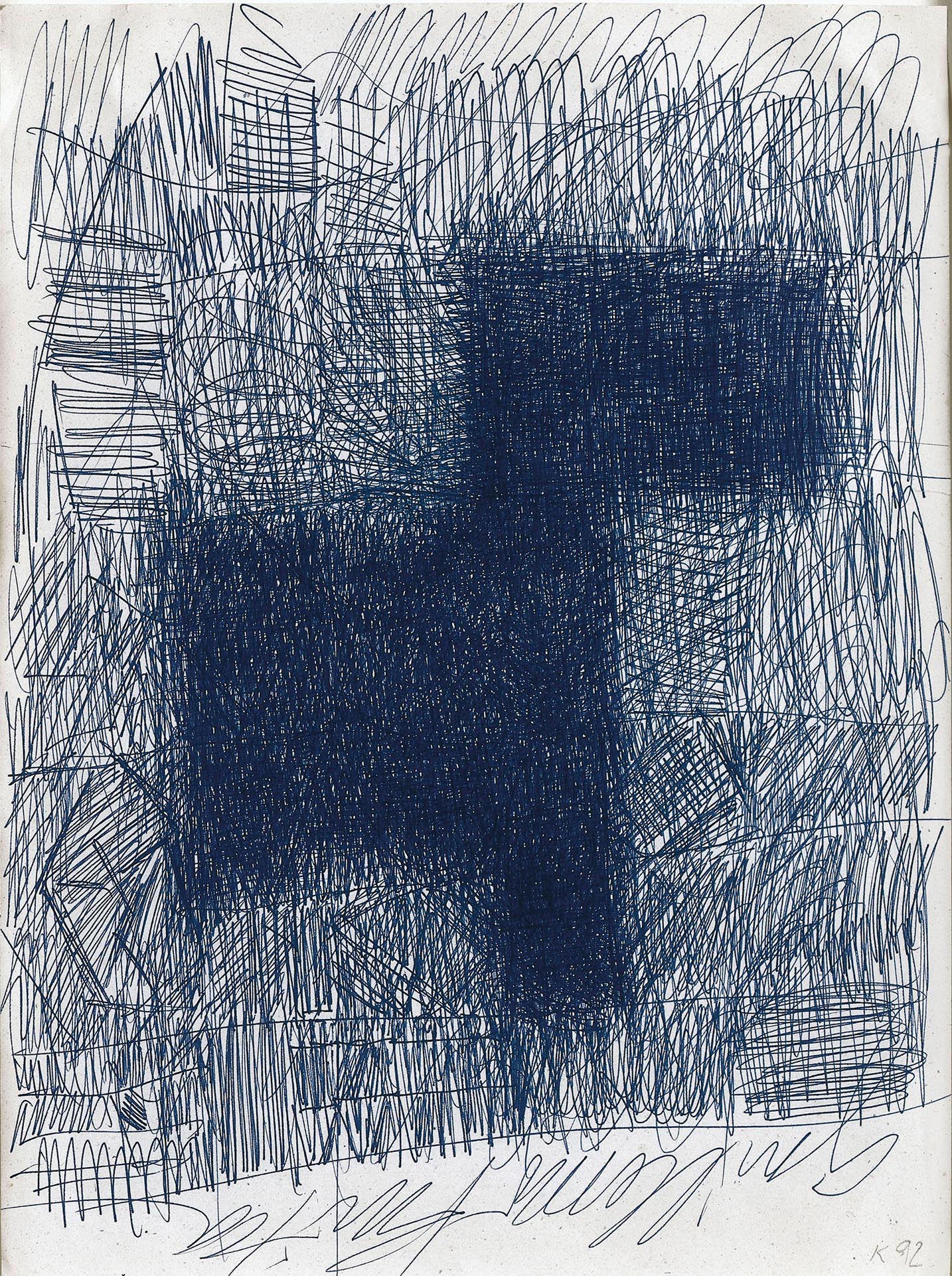

But how do these drawings relate to painting, presumably the artist’s “principal” medium? The key for understanding this relationship is found in some brief comments about each of the drawings in this compilation that Kuitca wrote in 1998 upon my request—a text we called Eight Day Diary. In these lines, published in a book that brought together the entire series of drawings, the artist did not hesitate: “The paintings are the beginning of the drawings.”1 1 Guillermo Kuitca. Drawings 1981–1996. New York, Sperone Westwater, 1998, n.p. Kuitca thus inverted the classic dynamics of the drawing as a sketch for the painting. Instead, he redefined it as an echo or a space for rethinking the pictorial work and a way of recapitulating the images already developed. The overall view also shows drawing to be a place where the artist can freely apply one of his central practices, which is “repertoire and expansion” (“repertorio y despliegue”), as he himself defines the dynamics of repetitions and variations. In this sense, Kuitca is someone who always has a pencil in his hand, drawing everything and anything, from mere scribbles (the basis for the Diarios series that he began in 1994) to highly accomplished drawings that come close to his paintings.

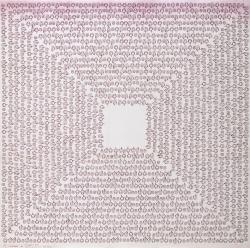

Originally selected by the artist and by the gallerist and publisher Gianfranco Sperone, this collection of drawings forms a space where we discover some of Kuitca’s vital visual processes. One instance is the multiplication of a sentence to symbolize imprisonment or insanity, repeated obsessively in his maps and apartment floor plans like a protective charm, as for example in the sentences “Gimme shelter” or “Ich habe genug”. Another is the persistently appearing stain, which in terms of the work could be a reflection, a haze, a flood, or blood, and in any case an indication of a dramatic situation and a revealed intimacy.

In brief, these drawings are not studies in the preliminary, preparatory sense of the word. They do not aspire to become paintings. They are, instead, posterior studies, occasions to continue thinking about an image, furthered by the swift contact that the immediacy of drawing allows. And in their entirety, they give shape to an anthology of drawings in their own right.

Inés Katzenstein, 2017 Inés Katzenstein is a curator, and works as Director of the Art Department at the Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

(Translated by Noel Smith)